Six of my ancestors emmigrated to the Puritan colony of Massachusetts Bay in 1633. Within 5 years, all of them would be exiled for heresy.

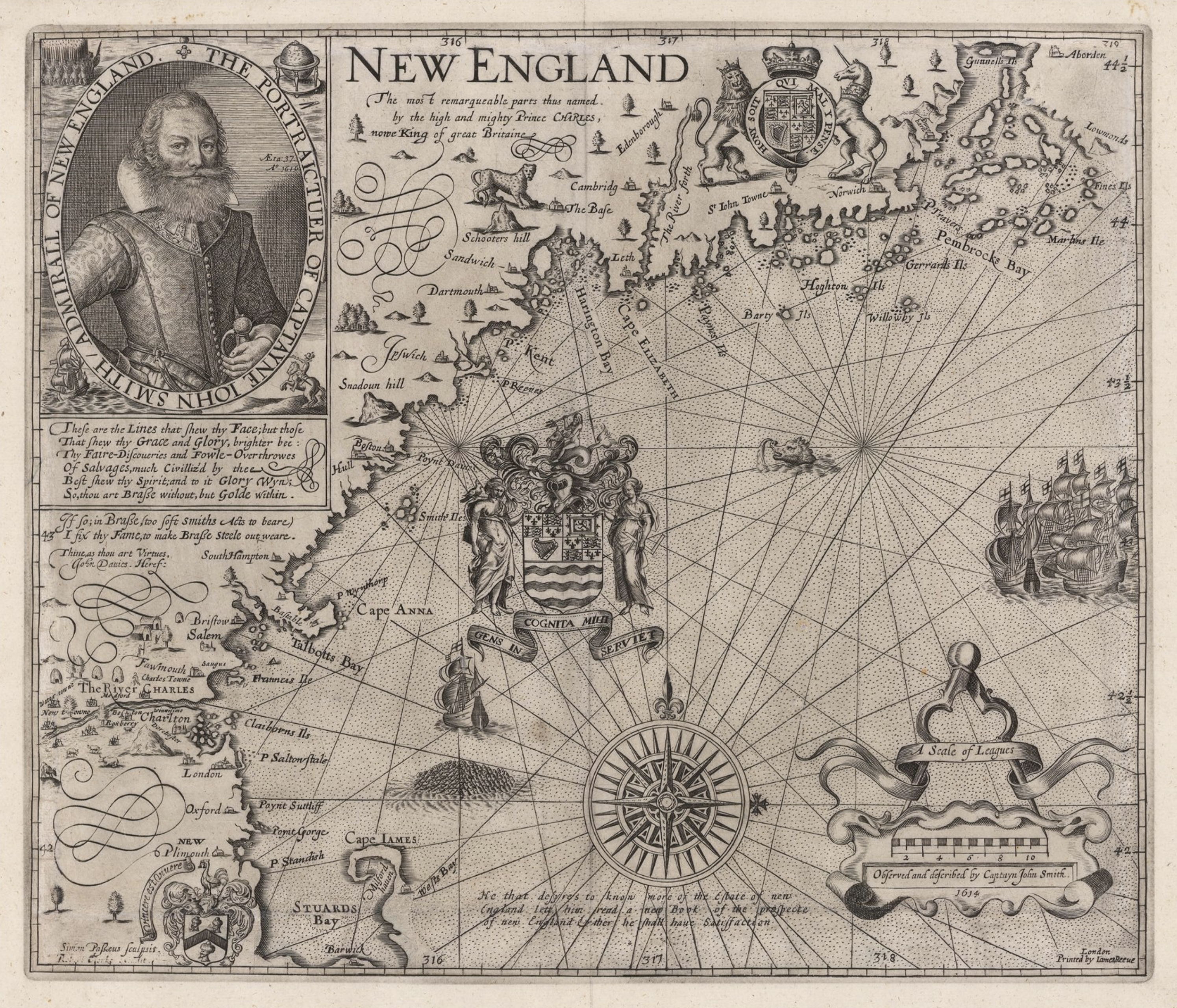

The colony itself was built on the ashes of the Dorchester Company which attempted a settlement at Gloucester. But the fishing was poor, the soil was rocky, and the settlers nearly went to war with Miles Standish and Pilgrims over fishing rights – so in 1629, the settlers abandoned Gloucester and found sanctuary with the Naumkeag tribe, at what would later be called Salem. By absorbing the assets of the failed Dorchester, the Massachusetts Bay Company started with one settlement in place.

In the summer of 1630, 11 ships and 700 settlers set sail for Salem. By Christmas, 200 of them would be dead. Still, Salem gave other settlements a chance to form, enabling 20,000 Puritans to lay down roots in Massachusetts Bay in the 1630’s – my ancestors, the Wilbores and the Porters among them.

The Columbian Exchange

In 1492, Columbus made first contact with the Taíno, and kicked off what is often referred to as the “Columbian Exchange” – that is, the widespread transfer of people, plants, animals, technology, and diseases between Europe, Africa, and the two American continents.

For Native Americans, this was a near-extinction level event. Measles, mumps, chickenpox, smallpox, diphtheria, influenza, pertussis, scarlet fever, typhoid, yellow fever, leptospirosis and cholera all arrived with the Europeans, their domesticated animals, and the fleas and rats aboard their ships. Each created a virgin soil epidemic as it spread across the 2 continents.

We know that the eastern seaboard was still densely populated in 1524 when Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed the length of it and reported that he, “saw great fires because of the numerous inhabitants.” By 1620, 90% of the native population on both continents was lost to diseases of European origin.

In Acadia, the Mi’Kmaq had good relations with the French when they came to settle Port Royal in 1604, but a Jesuit named Father Pierre Biard noted their dwindling numbers in 1611.

They are astonished and often complain that since the French mingle and carry on trade with them they are dying fast, and the population is thinning out. For they assert, before this association and intercourse, all their countries were very populous, and they tell how one by one, the different coasts, according as they begun to traffic with us, have been more reduced by disease.

1611. Father Pierre Biard, Nova Scotia

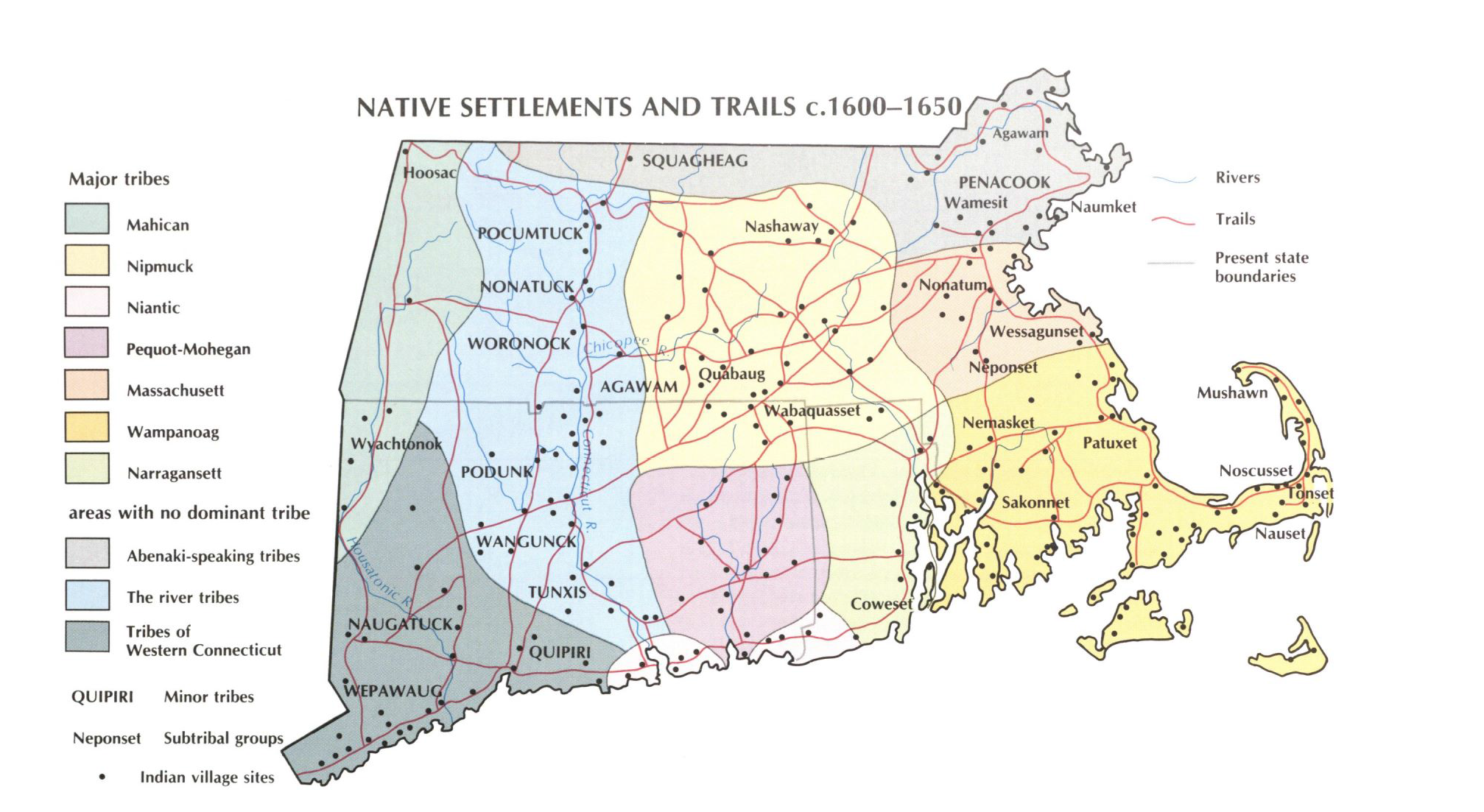

The Wampanoag called the first widespread New England plague The Great Dying. It began in Maine in 1616 and cut a path down the coastline, 30 miles wide, reaching all the way to the Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island. Symptoms included headache, fever, jaundice and hemorrhage but it’s cause is still unknown. It lasted until 1619 and in coastal villages 90-100% of the population died in this epidemic alone – and more would follow.

For in a place where many inhabited, there had been but one left to live to tell what became of the rest; the living being (as it seems) not able to bury the dead, they were left for crows, kites and vermin to prey upon. And the bones and skulls upon the several places of their habitations made such a spectacle after my coming into those parts, that, as I travelled in that forest near the Massachusetts, it seemed to me a newfound Golgotha.

1637. Thomas Morton. Merrymount (Quincy), MA

Using land under cultivation as a yardstick, estimates suggest a population of 60 million on both continents prior to 1492 – with 6 million surviving by the early 1600s. That represents a 90% loss of the Native American population, about a 10% loss worldwide. The impact can still be seen in Arctic ice core samples which show a drop in CO₂ levels bottoming out in 1610 – the result of reforestation on a continental scale.

…the good soyle, and the people not many, being dead and abundantly wasted in the late great mortalitie which fell in all these parts about three years before the coming of the English, wherin thousands of em dyed…ther sculs and bones were found in many places lying still above the ground, where their houses and dwellings had been; a very sad spectackle to behould.

1620. William Bradford, Governor, Plymouth

Early European Attempts At Settlement

In the first 128 years, most European attempts at settlement would fail, and most would fail within 2 years. Of 20 attempts made prior to 1600, only 2 settlements still survive. Of 14 attempts made between 1600-1620, and only 4 still survived.

But there was a sea change in the odds of survival after 1620. When the Pilgrims landed, they settled in a Wampanoag village previously occupied by the Patuxet, and abandoned in The Great Dying. It was a large, defensible, well-chosen position near fresh water. It was already cleared for agriculture and the Wampanoag were open to alliance. By building Plymouth on the foundations of Patuxet, the colonists got the toehold they needed.

So Patuxet became Plymouth, Naumkeag became Salem, and Shawmut became Boston, etc… The coastal tribes, still reeling in the aftermath of the epidemic, tolerated the settlers, and tensions between them were managed for almost 50 years.

But tensions grew between the European settlements as well. Even English settlements didn’t entirely get along. Puritans and Pilgrims, for example, didn’t like each other much. Both emmigrated to Massachusetts, originated in England and subscribed to a pared down version of Protestantism – but that is where the similarity ends.

Pilgrims were religious Separatists who broke with the Established Church and were chased out of England by James I in the beginning of the 1600’s. They were generally from the poorer classes and though they achieved a semblance of religious freedom in Holland, they did not have economic security and feared assimilation. Consequently, and ironically, the banished Pilgrims sought a charter from the English government to settle Plymouth Colony.

There were only ever a handful of Pilgrims. Of the 102 passengers on the Mayflower – less than half were actually Pilgrims – most were adventurers, tradesman and servants. They never actually settled in large numbers. Puritans, on the other hand, came to New England by the thousands – 20,000 in the 1630’s alone. Starting in 1629, they established the Massachusetts Bay colony, centered on Salem and Boston.

In general, Puritans were better educated than Pilgrims, and the founders of Massachusetts Bay Colony came mostly from the upper middle classes. There were 100 graduates of Oxford and Cambridge among them, which may explain why they founded Harvard just 6 years after arriving.

And Puritans were not Separatists. They never broke from the established Church of England – they just practiced a very strict version of the doctrine as Congregationalists – eschewing any Episcopalian remnants of Roman Catholic practice.

In the end, in 1691, the Pilgrim colony of Plymouth was absorbed into the Puritan colony of Massachusetts Bay.

Wilbores in Boston

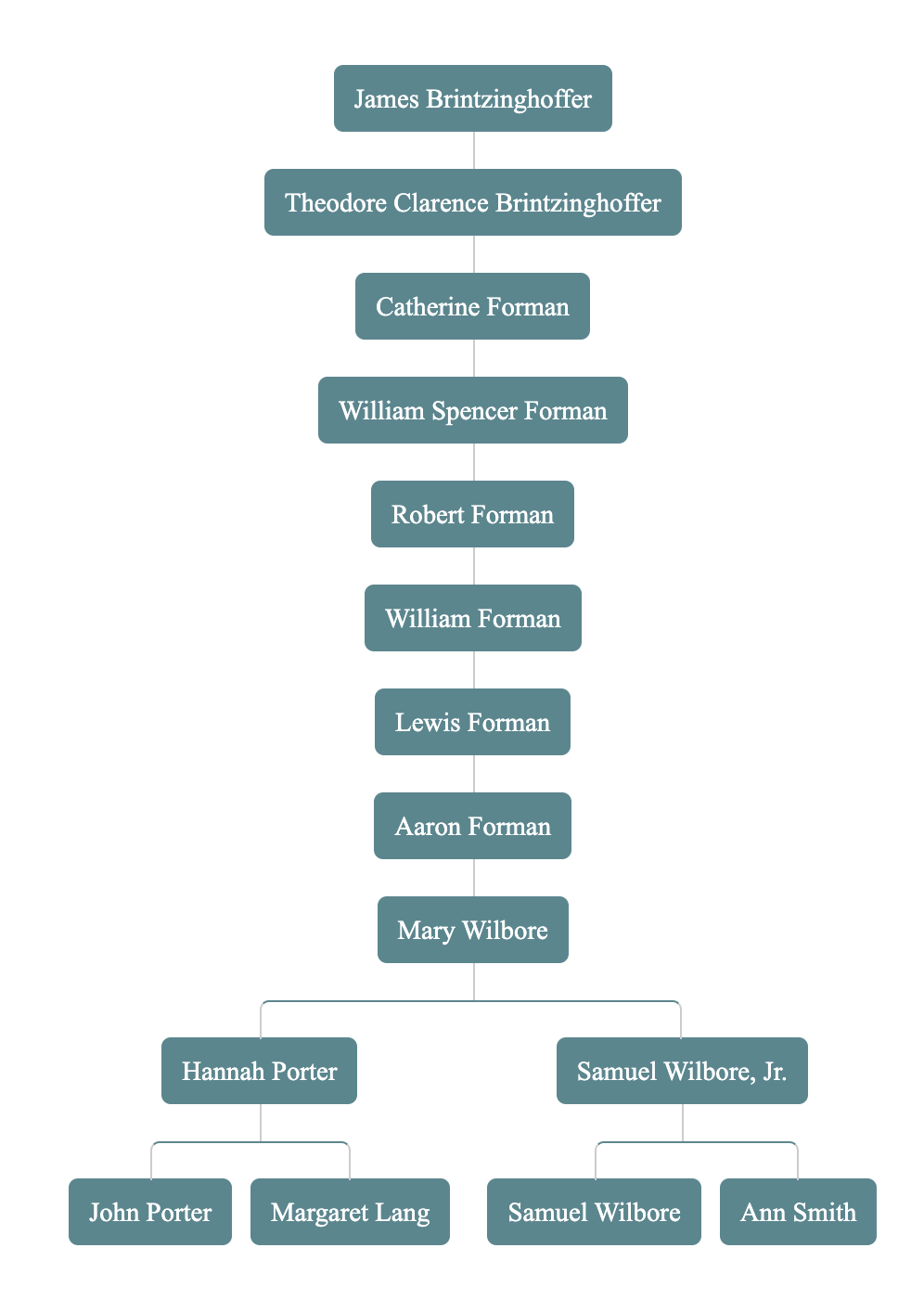

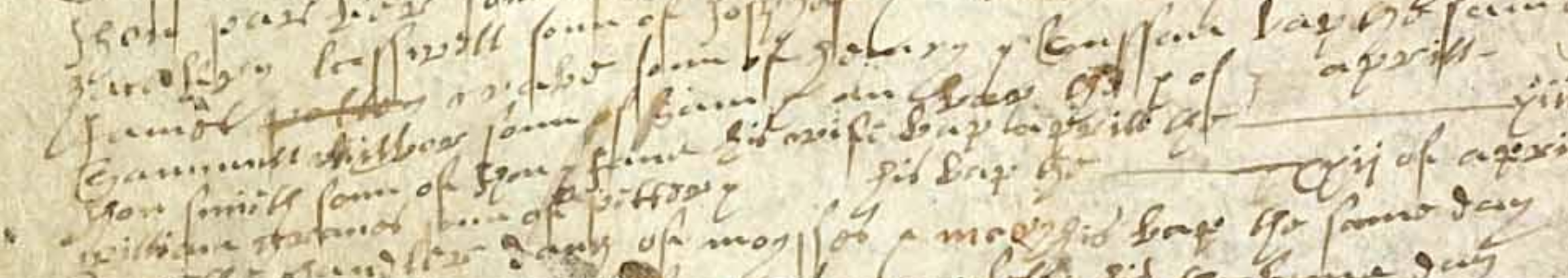

Samuel Wilbore and Ann Smith, my 10th great-grandparents, were born in Essex, England at the end of the 16th century. They married on 13 JAN 1619 at St. Peter’s Church in Sible Hedingham. They baptized their 5 children there – including their oldest, my 9th great-grandfather, Samuel Wilbore, Jr. If you want to walk in their shoes, that church is still standing and has been since the 14th century. It’s covered in medieval graffiti, and Roman tiles are still embedded in the brickwork.

There were at least 15 English ships landing in Boston in 1633 and we don’t know with certainty which they sailed on. We do know that Samuel and Ann joined the First Church of Boston on 1 DEC 1633, and that Samuel was made a Freeman on 4 MAR 1634 – so based on timing they probably sailed on the Griffin.

Samuel came from a family of merchants. His father Nicholas was a woolen draper and he probably did the same kind of work in Boston. But he also dabbled in linen and lumber, and was eventually part owner of both a planing mill and an iron forge in Taunton. Beyond his work as a merchant, he owned land – a lot of land – in 3 different cities over the course of his life in America.

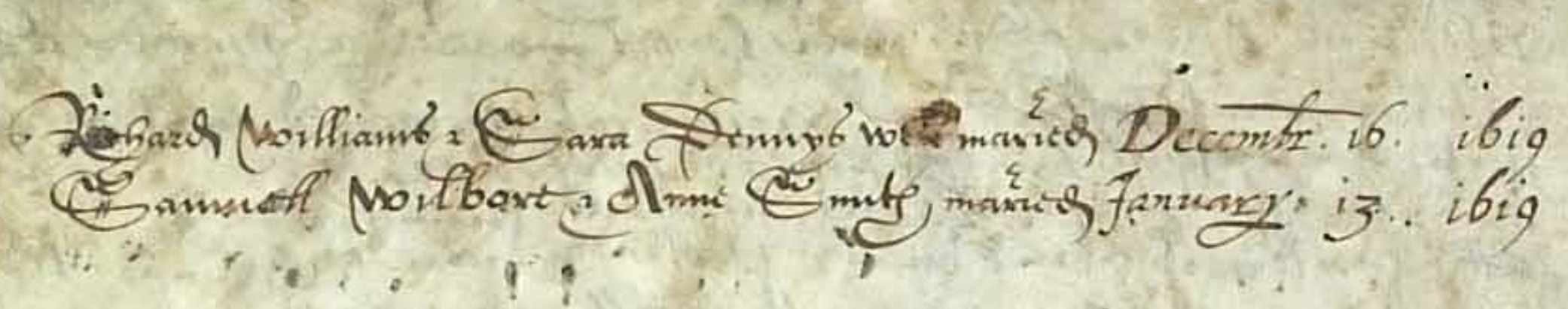

His name doesn’t appear on early maps of Boston, but there are several mentions of his land in the town records. It was close to the Colbourne and Eliot properties and, in 1638, he was given permission to sell his 2 houses to David Offley and Samuel Sherman. Taken altogether, we know his property was adjacent to The Neck.

It is agreed that there shall be sufficient foot-way from William Colbourne’s field-end unto Samuel Wylebore’s field-end next Roxbury, by the surveyors of highways by the last of next fifth month.

6 JUN 1636. Boston Town Records

At the time, Boston was almost an island, connected to Roxbury by a thin finger of land, and Orange St was the only road in or out of it. The Wilbore family lived on Orange St – later renamed Washington St. – on the Boston side of The Neck. To guard the approach, “brother Wilbore was to see to the making of the gate and stile next to Roxbury” (Town Records. 23 MAR 1635) and 6 men were constantly on guard there: 2 from Boston, 2 from Charleston, and 2 from Roxbury.

For a merchant, there was no better location. He was close to 3 settlements, the traffic running between them, with access to water for transporting goods by boat.

As a Freeman, Samuel could vote, hold public office and elect other Freemen. To qualify, he had to be a mature member of the Church in good standing, sworn to the crown, with personal assets of £40, or 40 shillings per year. He needed to have a ‘peaceable’ nature, and he had to profess to a spiritual experience in which God revealed his status as a member of ‘the elect’ – those chosen for salvation.

After a favorable vote by existing Freeman, he had to swear a fairly severe oath. Some Puritans found the wording so problematic, they preferred to go without the vote, rather than swear to it.

Freeman were also obliged to pay taxes and in NOV 1634 Samuel was made an assessor of taxes – which means that he definitely paid and also collected the taxes that purchased William Blackstone’s farm for communal use in 1634. You would know it now as Boston Common – the oldest park in America. It cost six schilling per household.

Porters in Roxbury

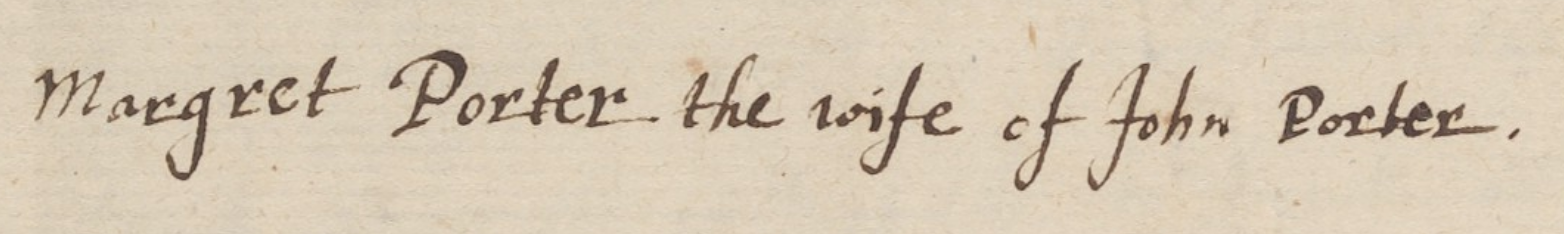

Margaret Lang was born in Essex, England around 1590. She married a weaver named William Odding, and had a child called Sarah before she was widowed in 1612. Her first husband’s will was filed at Braintree so it’s likely that Margaret was from there also.

Margaret’s second husband was a well-educated farmer named John Porter, and there was a big age gap between them. We think he was born around 1605 in Essex, and together they had one daughter named Hannah Porter. Margaret was around 40 at the time, and Hannah would be their only child together.

In the summer of 1633, they emigrated to Roxbury – across The Neck from Boston. We don’t know which ship they traveled on, but we do know they joined the First Church of Roxbury on arrival – the 74th and 75th members of that church. John swore his oath as a Freeman on 5 NOV 1633.

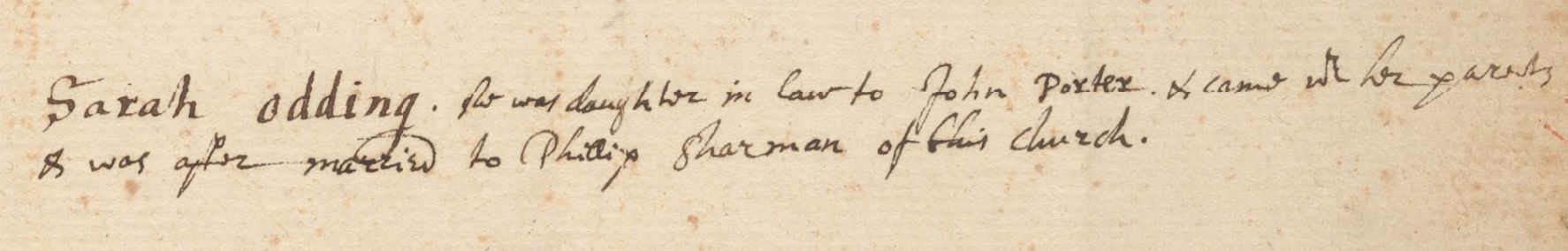

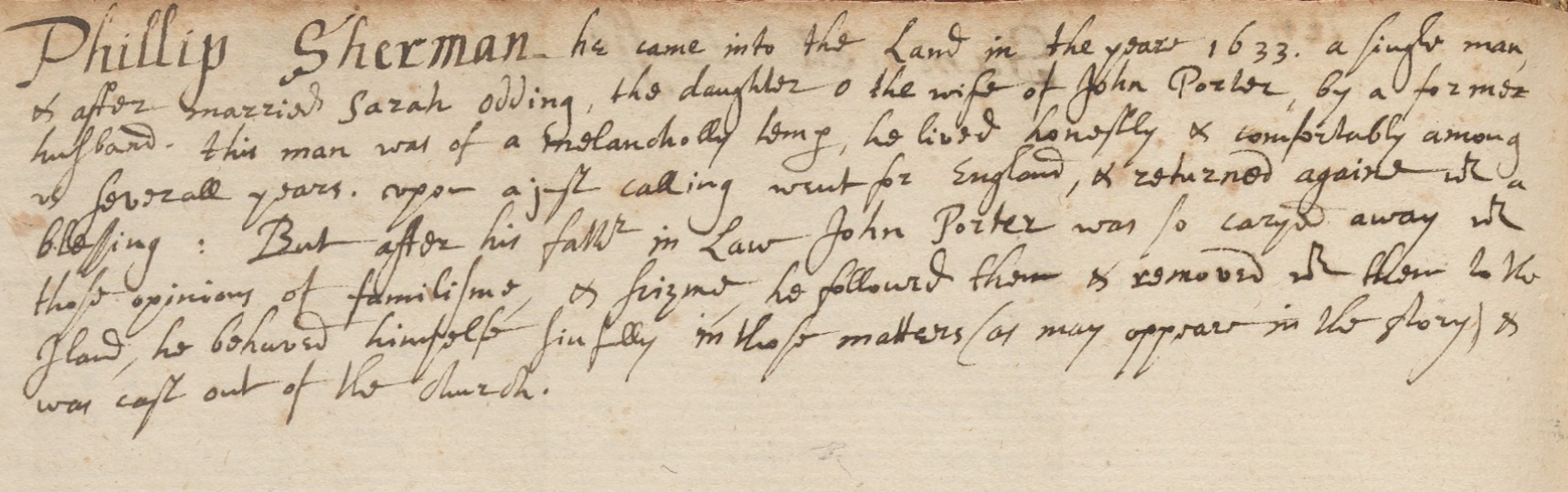

Margaret’s daughter Sarah, from her first marriage, married Philip Sherman soon after arriving. He was Church member #79 and probably traveled with them from England. Not much more is known about the next 4 years of their life in the colony, except that by 1637 Margaret, John and Hannah had moved into Boston, leaving Philip and Sarah in Roxbury.

The Heresy and Banishment

On 20 NOV 1637, Governor John Winthrop ordered Samuel Wilbore, John Porter and 57 other men to give up their guns, swords, pistols, powder and shot because the “opinions and revelations of Mr. Wheelwright and Mrs. Hutchinson have seduced and led into dangerous errors many of the people here in New England”.

The Antinomian Controversy (1636-38) was an argument over the finer points of Covenant theology. Puritans adhered to a Calvinist view of salvation. In short, God has already decided who he will save – so the faithful aren’t trying to earn salvation, they’re looking for signs that they’re already among the chosen.

Roman Catholic theology leans on a Covenant of Works – behave well, and you get into heaven. Puritanism leans on a Covenant of Grace – if you have an inward experience of God’s grace, you can be assured you are among the chosen.

But pious behavior and conformity were still incredibly important to Puritans, and a dispute arose around the role of it in spiritual life. The majority of Puritans saw good behavior as evidence of a state of grace. But some of Puritans, the ‘Free Gracers’, believed that this was dangerously close to teaching a Covenant of Works and smacked of popery.

Since, at its core, this was a theocracy, the dispute dragged over into politics. Governor Henry Vane attempted to resign over it, and was later voted out of office because of it. The courts stepped in and called for a day of fasting – hoping that repentance would lead to reconciliation. It didn’t.

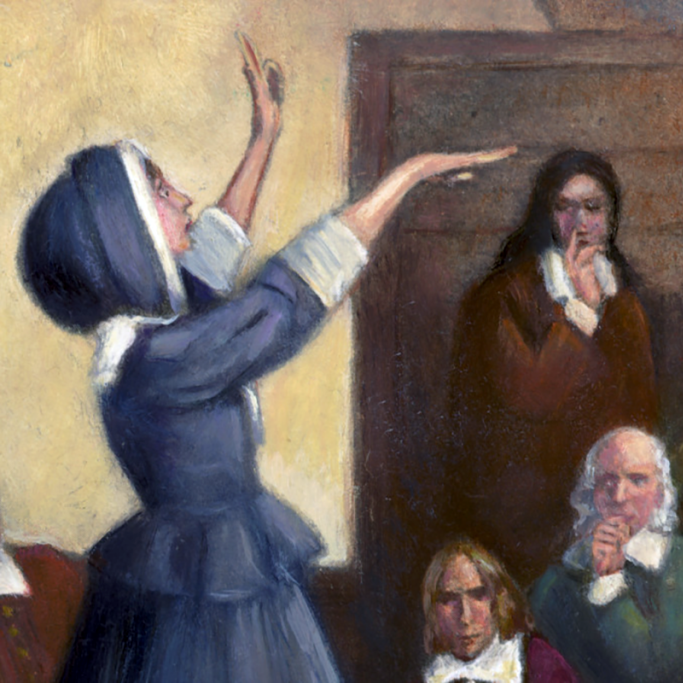

On the day of the fast, 19 JAN 1637, Reverend John Wheelwright, a Free Gracer, set the town on fire with a militant sermon, accusing town magistrates of being allies of the Antichrist. Fearing a coup, the magistrates took severe action against the dissenters – and many backed down, including 2 of the 4 Free Grace leaders. But John Wheelwright and Anne Hutchinson did not back down.

When enemies to the truth oppose the ways of the Lord, we must lay load upon them, we must kill them with the word of the Lord. The Lord hath given true believers the power over nations and they shall break them in pieces as shivered with a rod of iron…we must all of us prepare for battle & come out against the enemies of the Lord, & if we do not strive, those under a covenant of works will prevail.

19 JAN 1637. Rev. John Wheelwright

At the time, Anne Hutchinson was a midwife and a 46 year old, pregnant mother of 10. She was jailed, convicted of heresy and banished for promoting Free Grace in her prayer group. When her child was delivered stillborn and deformed, Governor Winthrop called it a demon and said it was proof that she was influenced by evil.

For his sermon, John Wheelwright was also banished after being found guilty of contempt and sedition. 40 men, including my ancestors, signed a petition in support of John Wheelwright, challenging the court’s right to try a matter of conscience BEFORE it had been examined by the church.

At the time, there were 831 Freemen in the colony and 96 men dissented during the controversy. 58 recanted their dissent immediately. Those who did not recant, were disarmed. 59 men were disarmed and offered a second chance to recant. Those who did not recant, were disenfranchised and banished.

In total, 38 men were disenfranchised and banished. They were given until 3 APR 1638 to leave the colony, or else be charged with a capital offense.

Dissenters flee to Rhode Island

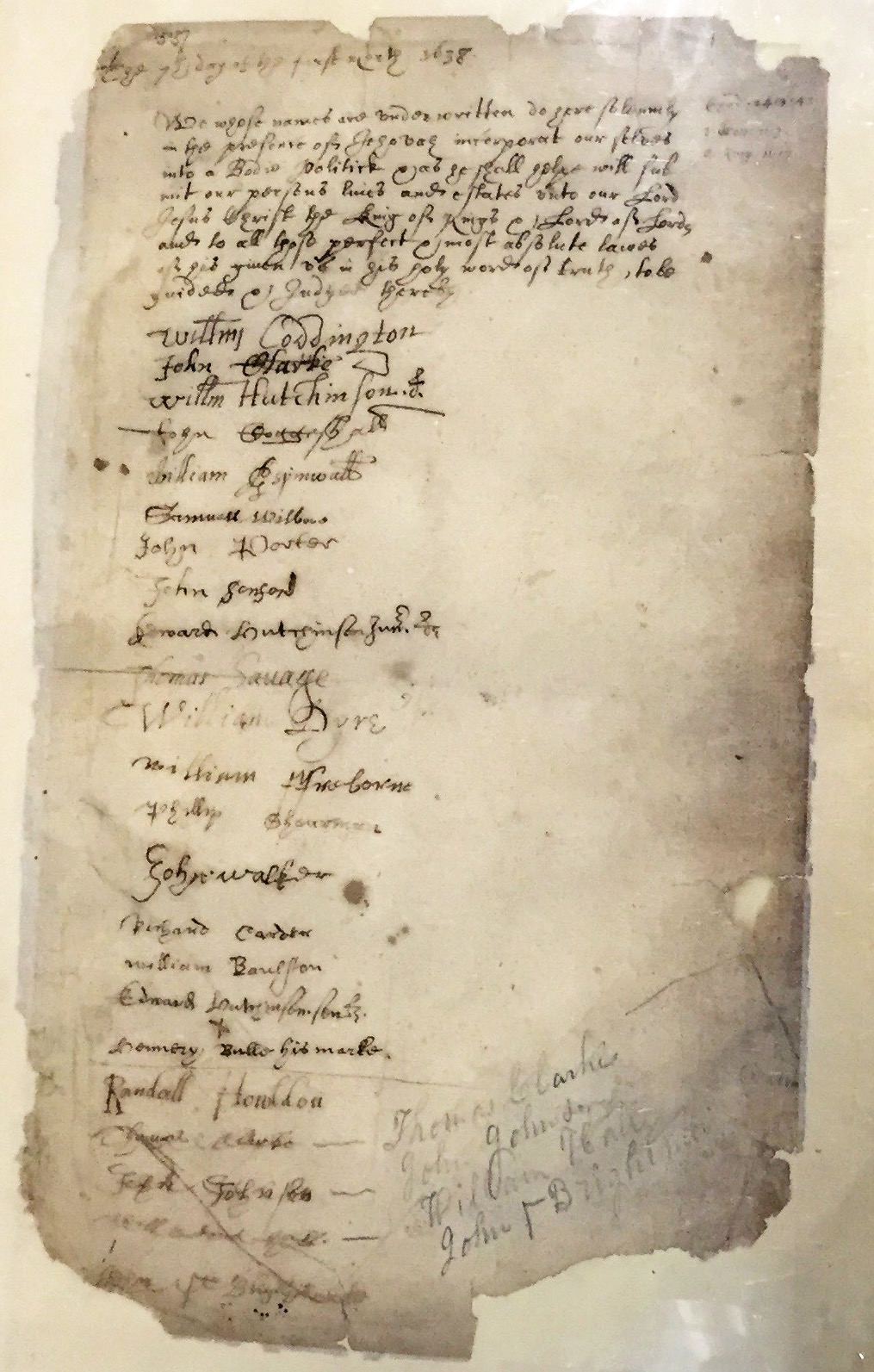

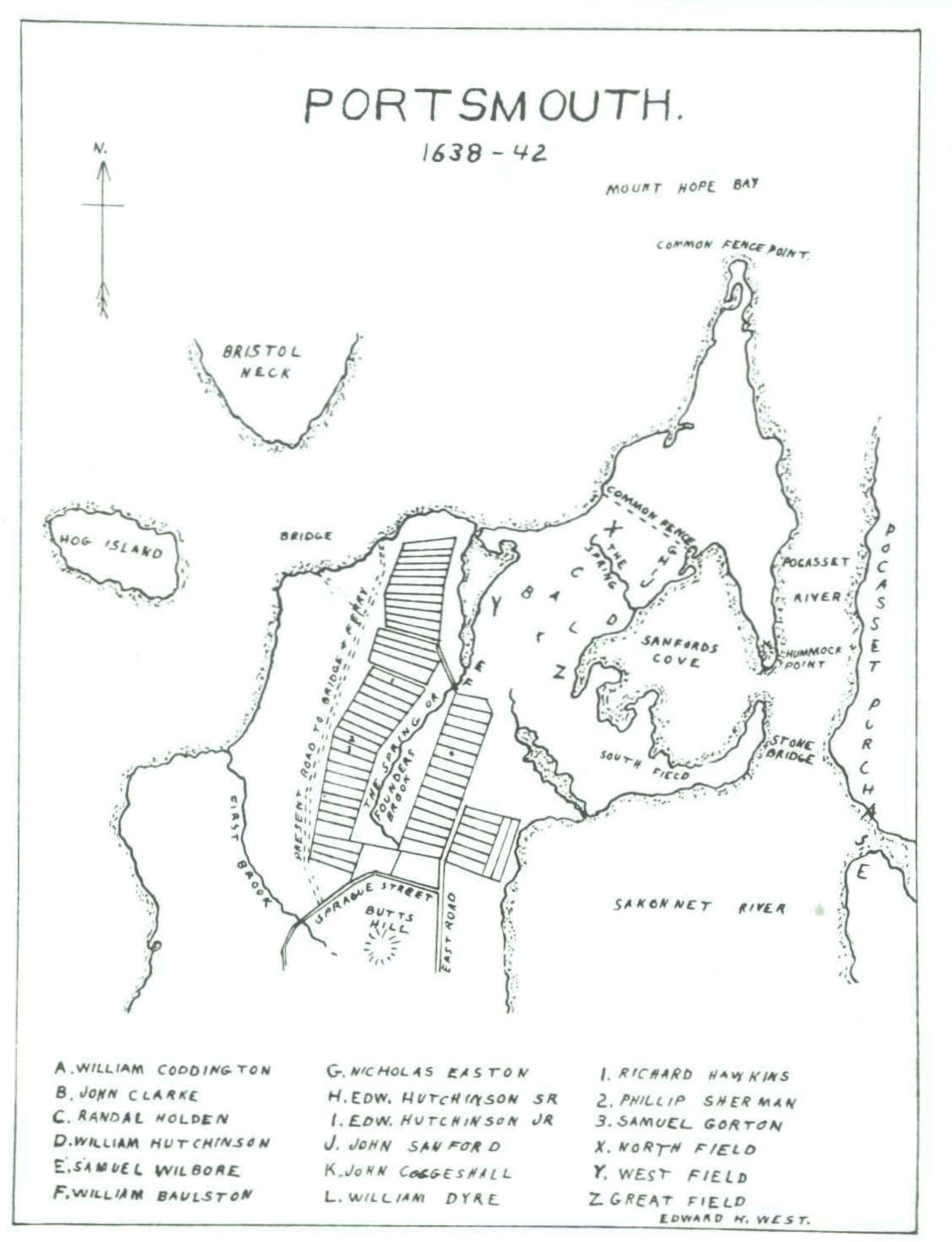

On 7 MAR 1638, shortly after their banishment, 23 of the Dissenters gathered at the home of William Coddington in Boston and signed the Portsmouth Compact, agreeing to form a new colony together, somewhere else.

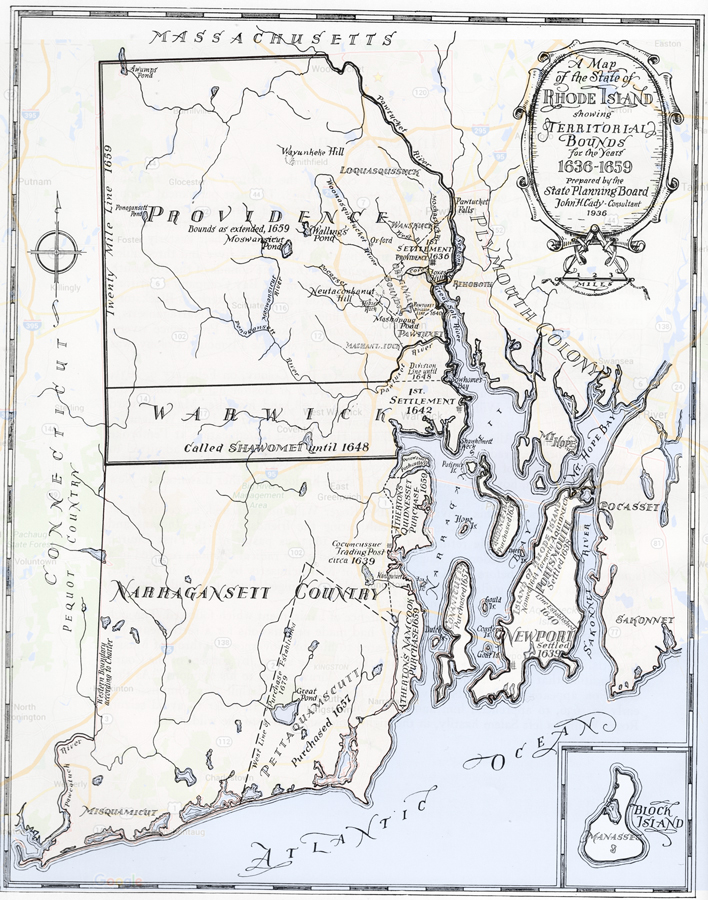

They considered a move to New Amsterdam but Roger Williams’ colony at Rhode Island guaranteed religious and political freedom. Founded in 1636, it was Christian in character but non-sectarian in governance. It also broke religious and political ties with England – the first English settlement to do so.

Williams brokered the sale of Aquidneck Island for them with Narragansett sachems, Canonicus and Miantonomi, for forty fathoms of white beads, ten coats and twenty hoes. Samuel Wilbore and John Porter were each given plots on the west side of the island and, today, Portsmouth and Newport are situated at either end of it.

Wilbores are banished, sorta …

We know that Ann Smith passed away before 29 NOV 1645 because that’s when her husband remarried. It’s not clear when or where she died but she would have been about 30 when they landed in Boston and around 35 when they fled to Rhode Island – if she was even still alive at the time. She was certainly gone before the age of 41.

Just after his banishment, in JUN 1638, Samuel was given permission by the Massachusetts Bay colony to sell his property in Boston to a suitable Puritan buyer. That same month, he was made clerk of his new colony’s militia. Over the next 12 months, he was granted land, became a Constable and established trade with the Narragansett sachems. Then, having fully established himself in Rhode Island, he returned to Boston to recant his heresy.

Whereas I joined with others in presenting to the corte a writing called a petition or remonstrance, I confess it was far beyond my place and range to use such unbeseeming expressions to those whom the lord hath set ouer me, therefore entreat your worships to understand that it is only the cause which made me to doe it, and for my rashness and offence therein I humbly crave your worships prayers to the lord for pardon and pardon from yourselves: I have been no enemy to this state nor through the Assistance of the lord I hope never shall.

1639 MAY 16. Samuell Wilbore.

He seems to have been living in Rhode Island at least until 13 MAR 1644, when he was re-elected clerk of the militia. But his second wife, Elizabeth, was made a member of the Boston church on 29 NOV 1645 – so by then he was also living in Boston.

It appears he left his oldest son, Samuel, Jr., in Rhode Island to tend his land and interests there. Then, sometime in the 1640s, he expanded into Taunton, in the Pilgrim colony of Plymouth, picking up more land and a part-interest in an iron forge. He left that property under the care of another son, and spent his final years at his home on Mill St. in Boston.

When he died on 6 NOV 1656, aged 62, he had holdings in 3 separate colonies – Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth and Rhode Island – a hard won lesson in risk distribution. His last will & testament was proved 6 NOV 1656.

Mrs Porter sues for Alimony

John Porter was an active presence at town meetings during the founding of Rhode Island. He was a Freeman and one of only a handful of men sent to survey and establish property boundaries in the first 2 years of settlement. Over time, he amassed thousands of acres in Portsmouth, Newport and South Kingston. He served as Assistant to the Governor 7 times between 1640 and 1664, and he was made Commissioner 4 times between 1658 and 1661. He was a prominent figure, and 1 of only 22 men called out by name in the Royal Charter of Rhode Island in 1663.

So it’s ironic that after 30 years of public service, most of the written record related to John is about his infidelity and abandonment of his older wife, Margaret.

Sometime in 1664, John moved to his property in South Kingston with Herodias Long, a woman almost 20 years his junior – abandoning Margaret in Portsmouth, without any means of support. John would have been about 60 at the time, and Margaret about 74.

Under Puritan law, Margaret couldn’t vote or own property – she was entitled to nothing. Yet, on 5 JUN 1665, she successfully petitioned the Assembly and had John’s assets frozen until he provided for her support “to her full satisfaction” – which he did, 3 weeks later on 27 JUN 1665.

John gave Margaret the lifetime use of 240 acres of land in Portsmouth and then sold that land to Richard Smith on 26 SEP 1671. From that we can guess that Margaret Lang Odding Porter died within 6 years of her property settlement, and probably in the summer of 1671.

Wheras ther hath ben a petition presented to this presant Asembly margrett porter the wife of John porter of This jurisdicyion of Rhod Iland; in which The said margrett doth most sadly Complaine that her said husband is destitute of all Conjugall Love towards her, and sutable Care of her; is gone from her and hath Left her in such a nessesetous stat that unavoydably she is Brought to a meane dependance upon her Children for her Dayly suply, to her very great griffe of heart and the Rather Considering that ther is in the hands of her said husband a very Competant Estat for both ther subsistance; and Therupon the said margrett hath most Earnnestly Requested this gennerall asembly to take Care of her and to take her deplorable Estate Into your serious Consideration, as to make some sutable provition for her Reliefe out of the Estate of her husband, and that spedily before both hee and it be Convayed away. The Court therfore Taking the matter into ther serioues Consideration and being Thoroughly satisfied, both by Common fame and otherwise, That the Complaints are True; and that the feares premised of convaying at least his Estate away are not without grownds; and haveing a deep sence upon ther hearts of this sad Condition which this poore anciante matrone is by this menes Reduced into … bee it by the said Court and the authority thereof decreed and Enacted that all the Estate, bothe personall and Reall of the above said John porter, Lying and Being in this Jurisdiction is hearby secured as if actually seazed upon and deposited for The Reliefe of the aforesaid Complainant…untill hee hath settled a Competent Reliefe upon his ageed wife to her full satisfaction…

1665 JUNE 5. Rhode Island Colonial Records

Soon after John settled with Margaret, the court pursued him for his irregular living situation. Herodias Long – a Quaker with 2 living ex-husbands – was well known to the Puritan assembly, and no one believed she was his housekeeper.

On 24 OCT 1666, John was called into court to explain himself, but he failed to appear. The court issued a new summons for the next session in MAY 1667, but he didn’t show up for that either. Another summons was issued for 28 OCT 1667 and when John failed to appear for 3rd time, they fined him and formally charged them both with cohabitation “Soe as to live in a way of incontinency.” A 4th summons was sent requiring him to appear at the spring session.

If you’re looking for the word ‘adultery’ in the record – you won’t find it. Married women could be charged with adultery – which was sometimes punishable by death – but married men could only be charged with fornication. So John couldn’t be charged with adultery because he was a man and Herodias couldn’t be charged because, technically, she wasn’t married. She was legally divorced from her first husband on the grounds of adultery with a man named George Gardiner. She spent 20 years with Gardiner before leaving him for John, but they were never actually married. When she came to John she had 9 children by 2 men, and no legal husband.

John was finally tried by jury for cohabitation and inconstancy on 11 MAY 1668, almost 4 years after he left Margaret in Portsmouth, and was quickly found ‘Not Guilty’. He represented Herodias the following spring – she never actually came to court on this charge – and she was also found ‘Not Guilty’. The record says nothing about their testimony, it only records that they paid court fees and were cleared by proclamation.

John Porter of Narragansett in the Kings province and Harrud Long alias Gardiner for that they are suspected to Cohabitt and Soe to live in way of incontinency : Mandamassis beinge sent forth, And they in Court Called Did not a peere. The court upon consideration of the matter, Not being informed that the Mandamassis were delivered to the persons in time the court doe order that the Mandamassis shall be sent forth to them again to appeare at the next court of Tryalls where if they appear Not they shall be proceeded with as guilty persons.

1667 OCT 23. Rhode Island court records

Upon indictment by the solicitor for living in a way of inconstancy with Herrud Long (alias) Gardiner. The sayd John Porter being Mandamassed and in court called, pleads not guilty and refers himself to the country for tryall. The jurris verdict. John Porter. Not Guilty. The court doe order that the sayd John Porter is cleered by proclamation paying fees.

1668 MAY 11. Rhode Island court records

John Porter apeereing with a paper signed Horrud Long the Court doe owne him her Aturney: the sayd Mr porter in her behalfe: pleads Not Guilty of Liveinge in incontunancy and Refers her Tryall to god and the Cuntry The Juris verdict – Horrud Long not Guilty by punktual Testimonys. Judgement granted. The sayd Horrud Long cleered by proclamation in open court. Paying fees.

1668 OCT 21. Rhode Island court records

By 1671, Herodias Long was using John’s surname and they jointly signed several contracts giving part of John’s land to some of her sons by George Gardiner. They lived ‘as married’ and may have actually been married after Margaret’s death but there is no documentation to prove it.

The last document pertaining to John is a lawsuit filed against him on 11 MAY 1674 by Richard Smith, the man who bought Margaret’s Portsmouth property. John lost that suit and given the lack of further mention, he probably died shortly after. He was certainly gone by APR 1692, when Herodias’ sons by George Gardiner represented themselves as John Porter’s heirs in a meeting of the Pettaquamscutt Purchasers.

Samuel Wilbore, Jr. & Hannah Porter

Hannah Porter was a toddler when she emigrated in 1633 and Samuel Wilbore, Jr. was just 11. Their families were banished from Boston only 5 years later and by the time they married in 1648, tensions were escalating in New England.

Samuel, Jr. would have served in the Rhode Island militia from the age of 16 on. He was elected to the rank of sergeant when he turned 21. By 31, he was managing defensive and offensive preparations for the entire colony.

The Wilbores. 1633-1678. Town & Church Record Transcriptions

In 1656, the year Samuel, Jr.’s father died, the town council ordered a public watch to be formed in all precincts. The constable and the clerk of the militia went door to door taking an inventory of guns in the town, with the authority to press any extra weapons into public service, if needed.

Samuel, Jr., by this time a Lieutenant, was sent to the mainland with 6 other men to tell the Narragansett sachems to keep their people off the colony’s island. There must have been some tension with the Narragansett, but the immediate cause of it isn’t clear to me.

Epidemics continued to devastate native nations. Ongoing immigration drove settlers further and further into native territories. There were repeated conflicts related to control over trade and land sales and, as alliances shifted, economies and colonies collapsed.

17th Century Conflicts

Samuel spent most of the late 1650’s acquiring land – first in Portsmouth, then in South Kingston. He was a part of the group that purchased Pettaquamscutt from Quassuchquansh, Kachanaquant, and Quequaquenuet, Chief Sachems of the Narragansett. It was a commercial venture for them. They broke it up into parcels – keeping some, selling some, and expanding their personal holdings over the next 10 years. But as more and more land changed hands, disputes arose over ownership and, like many people, Samuel, Jr. spent much of the next decade defending his title.

In 1661, at a Plymouth Colony meeting, Ninnegret, Stulcop, Weeweekeuett and Sucqcash – sachems of the Niantic and Narragansett – protested the presence of Samuel, Jr.’s livestock and settlers at Point Judith. They asked Plymouth to intercede with Rhode Island on their behalf but when that failed, the sachems wrote directly. They told Rhode Island that if Samuel, Jr. didn’t submit to a court hearing to adjudicate their claim, they intended to drive him off the land by any means necessary.

Now we knowing that we have not sould them any land there, and being thus injuriously dealt with withal by them, we are forced to make complaint to yourselves by the Commissioners of the United Collonies, hereby protesting against the said Samuel Wildbore and companie for their so unjust actings, and crave that this, our protest, may be received by you, and kept upon recorde by you as our acts and deeds, and crave that it may not be offensive to any English, if that Samuel Wildbore and his companie will not come to any faire trial either before yourselves, or some other indifferent judges, if then we endeavour to drive their cattle away, or take any course whereby we dispossesse them.

Powtuck, Ninecraft, Econickamuck, Scutabe, Quequegusewet (AKA Gideon), Masipe (AKA Susquansh). Sachems of the Niantic and Narragansett. 9 SEP 1662

In AUG 1661, another group – this time English settlers – pressed a claim against him. The Narragansett sachems, they said, had sold the land to them. They also attempted to forcefully retake it. Neither group succeeded. Samuel, Jr. left his land on Point Judith to his daughter Elizabeth, and bequeathed over 2000 acres in Narragansett country to his other descendents, including my ancestor, Mary.

The pivotal event of Hannah and Samuel, Jr.’s lives was probably Metacom’s War. After years of tension, in 1675, Metacom, leader of the Pokanoket tribe and the Wampanoag nation, unified the Wampanoag, Nipmuck, Podunk, Narragansett, and Nashaway in a regional war against the colonists. It was brutal and decisive. It lasted 3 years in total and was the last Native American attempt to remove European colonists from New England.

Samuel, Jr. was 53 years old when the war broke out and a Captain in the militia. There is no question that he would have led and served in this war, and that it would have impacted them both greatly.

For the colonies, it was devastating. More than half of New England’s settlements were attacked. 12 of the 90 settlements were totally destroyed, including Providence. The Plymouth and Rhode Island economies were left in shambles and their populations were decimated. More than 1,000 colonists died, about 10% of the adult male population.

The war largely ended with Metacom’s assassination in 1676, but continued in northern parts of New England until 1678. As his allies abandoned him, Metacom was shot and killed by a formerly close associate, a subsachem named John Alderman. His dead body was drawn and quartered, and his remains desecrated. His head was mounted on a pole at Plymouth for 20 years and his hands were sent to Boston for display.

2,000 native men died in the conflict. 3,000 more died of sickness or starvation. 1,000 were sold into slavery or put to indenture, including Metacom’s wife and son. Some 2,000 others fled the region. Estimates suggest that the war reduced the Native American population of 20,000 by between 60 and 80%.

Given Samuel, Jr.’s prominence in Rhode Island, it’s not surprising that he was a key figure in exacting retribution after the war. It’s painful to read, but it’s not surprising. He served as a member of a Court Martial at Newport which executed several Native Americans for being complicit in Metacom’s War. He was also in charge of indenturing Native Americans after the war ended.

His order to indenture a 14 year old boy called Peter, son of a woman named Meequapew, for a period of 10 years is particularly heartbreaking, and comes 2 years after the fighting ended.

This Indenture made the Twenty Seventh day of the month called Aprill in the year one Thousand Six hundred Seventy Eight witneseth that William Cadman, Samuell Wilbur, and Robert Hodgson, all of the Town of Portsmouth in the Colony of Road Island and Providence plantations in New England being By publick authority appointed and Impowered to dispose of Indians and place them out as apprentices in the Said Town of Portsmouth: have by these presents put, placed, and bound, a certain Indian boy Called peter who is the Son of one Meequapew an Indian Woman late of pocasett, as an Apprentice unto William Wodell of Portsmouth aforesaide as an apprentice with the Said William Wodell his Executors administrators and assigns to dwell for the full term and time of ten years from the day of the date hereof to bee Compleat: by and dureing all which Said time of ten years the Said peter Shall well and faithfully Serve his Said master William Wodell his Executors administrators or assigns in all Such Lawfull as by him them or any of them he the said peter Shall bee put to or commanded to doe according to the best of his skill power and abillity: and the Said William Wodell dureing all the Said term Shall provide and alow or Cause to bee provided and alowed to his Said aprentice Sufificient food and Rayment and other nessesaries meet for Such an apprentice, and at the End of the Said term Shall yield unto his Said appentice his freedom from this his said Servitude which will bee when the Said peter Shall bee twenty foure years of age. Witnes our hands and seals

1678 MAY 15. The early records of the town of Portsmouth

Wm Cadman [seal]

Samuel Wilbur [seal]

Robert Hodgson[seal]

The above written is A true Copie of the origionall Entred and Recorded the : 15th of the 3rd month 1678 – John Anthony Town Clerke

Samuel, Jr. would serve consistently in the militia and government for the remainder of his life. He was 1 of 22 men called out by name in the Royal Charter of Rhode Island. He was a Freeman. He served repeatedly as Juror, Commissioner, Deputy for the General Assembly, Town Councillor, and Overseer of the Poor. He died sometime between 20 AUG 1678 and 1 DEC 1679.

Hannah Porter outlived her husband by several decades. She also outlived her only son, who died without heirs. Because of that, Samuel’s will had to be revisited. As Executrix, she gave and signed a statement with the court and I can’t tell you how unusual it is to have direct testimony from a woman in this period. She finally died 6 APR 1722, age 92.

Whereas my Husband Samuel Wilbur did in this within written will after my decease Give and bequeath all his housings and Land situate in Portsmouth on Rhode Island within mentioned unto my son John Wilbur and his heirs fforever male or female And if my said son John Wilbur should decease without issue that then the said Lands and housings to be equally devided between his three younger sisters or to whom or which of them that shall be then surviving: now, I the within named Hannah Wilbur being widow and executrix unto my within named deceased Husband, Samuel Wilbur do ffor me my heirs and Assigns and for every of us hereby ffreely and ffully Confirm the said Gift unto the survivors of my said three youngest Daughters and their heirs and Assigns forever equally according to this my said Husbands Last Will and Testament to be possest by them after my decease abovesaid In Witness Whereof, I the said Hannah Wilbur have hereunto sett my hand and seal the Thirteenth day of the Twelfth month called FFebruary in the year of the Lord one Thousand seven hundred and Eleven 1711/12. Signed sealed and delivered

Hannah Porter’s WIll

Hanna Wilbur [Seal]

In presence off Roger Burrington The above named Hannah Wilbur per John Anthony personally Appeared the day and year Last above written and acknowledged the above written instrument to be her voluntary Act and Deed before me, George Brownell, Assistant.

The above written is a true copie of the originall Entered and Recorded the 14th of the 12th month 1711/12 by me John Anthony Town Cleerke.

So how does it all end for these six ancestors?

Samuel, Jr., married Hannah Porter and their child, Mary, my 8th great-grandmother, was the first generation born in America. She left New England as a teenager around 1684 when she married Samuel Forman of Long Island. They sold off her inheritance in the Narragansett territory and bought a large tract of land in Freehold, NJ.

So my family left New England in 1684 – 8 years before the Salem Witch Trials, 6 years before the Plymouth Colony would be absorbed into the Massachusetts Bay Colony and 91 years before Lexington and Concord. This line of my family was only in New England for 51 years, but it was an incredibly consequential half century.