James Brintzinghoffer ← Theodore Clarence Brintzinghoffer ← Theodore Canfield Brintzinghoffer ← Washington Andrew Brintzinghoffer ← Georg Christoph Brenzighofer ← Johann Georg Brenzighofer ← Georg Melchior Brenzighofer ← Hannß Jörg Brintzighofer ← Hannß Michel Brintzighofer ← Hannß Brintzighofer

My grandfather, James Henry Brintzinghoffer, was very proud of his German roots and his family’s long history in America. He once told me they came over on the Mayflower – which wasn’t quite true – but it was closer to true than any of us realized until long after he was gone. James Henry had English relatives in Salem by 1624, and French Huguenot & Dutch relatives in New Amsterdam by 1622.

But this is the story of his German roots and his German name which is a long and winding path all its own. To help you follow along, I have bolded the name of any direct ancestor the first time it appears.

A special note of thanks to Eric Brintzinghoffer. He generously shared his extensive prior research into this family line and I owe him a debt of gratitude for his engagement and support.

What’s in a Name

You can’t talk about Germanic heritage without covering a few simple truths about German naming. To begin with, you can’t pay attention to the first name. A father might have 3 or 4 sons named Hannß – it doesn’t matter – they would all be called by their middle name. Sometimes people were recorded using both names, sometimes only one of the two.

You also have to watch for different Germanic forms of the same name for the same person: e.g., Georg|Jörg, or Johanness|Hannß|Hans. It can be confusing but, remember, English names have similar variants: e.g., Robert|Bob, Richard|Dick, Margaret|Peg.

Compounding that confusion, surnames didn’t come into regular use until the 1690’s. They might be patronymic (e.g., Robertson), occupational (e.g., Weaver), geographical (e.g., Berlin) or descriptive (e.g., Langbein/Long Leg). There isn’t always consistency in the use or spelling of a surname.

People, even in the course of a single lifetime, appear in the parish register using wildly different spellings of the family name. To understand that, you need to remember that ministers were recording the names of illiterate people and working just from the sound of the name they were given. They couldn’t ask, ‘How do you spell that?’

Just for extra confusion, women sometimes had an ‘in’ tacked onto the end of their surname and ministers had astonishingly illegible handwriting making later transcription prone to errors and typos.

Remember all of that when you see 10 generations of the same family interchangeably referred to as Brenschenhafer, Printzighofer, Printzig, Prinzig, Prinzing, Prinzikofer, Brintzighofer, Brinzighofer, Brinzighoffer, Brintzig, Brenzighofer, Brenzenhofer, Brenzikofer, Brintzeghoffer, Brentzenghoffer, Brintzinhoffer, Brentzig, Brenzighe, Brenzighakres, Brenhofer and Brintzinghoffer.

Finding Sersheim

You’ve probably heard that the Brintzinghoffers came from a small town in Germany called Sersheim – and that’s mostly true.

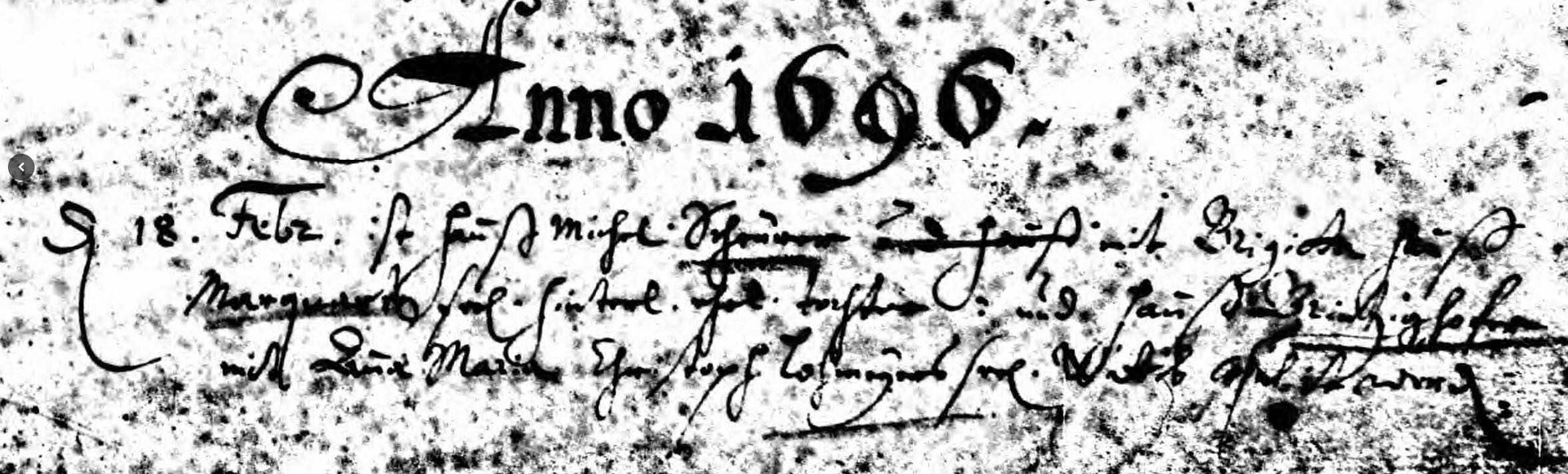

My 8th great-grandfather, Hannß Michel Brintzighofer married his first wife in Sersheim in 1696, in a church that still stands today. When he married for the second time the following year, a scribble in the margin indicates that he was born on JAN 3, 1672 in Weilimdorf, not Sersheim.

We know from his 1672 Weilimdorf birth record that his parents, my 9th great-grandparents, were Johannes & Albertine Elisabetha Brenschenhafer – and this is the earliest documentation I’ve found for the family, and the earliest I am likely to find.

Hannß Michel had a sister born in Bönnigheim in 1676, and another born in Sersheim in 1677, so we know with some certainty when the family arrived – and for 6 generations and 130 years, they made Sersheim their home. But before that, they were on the move.

To understand the Brintzinghoffers in this period, you have to understand the Thirty Years War (1618-48). It was ostensibly a conflict between the Catholic and Protestant states of the rapidly disintegrating Holy Roman Empire, but it quickly escalated into a wider territorial war, and it’s estimated that 8 million people died as a result. Many areas involved in the conflict were almost entirely depopulated. Alsace-Lorraine was so depopulated, the King of France offered religious freedom to the Swiss if they would settle there. Switzerland had been neutral in the war but it’s economy suffered and some of its cantons were actually overpopulated.

The Kraichgau area of southwest Germany was likewise decimated and the small town of Sersheim was reduced from 800 to just 50 residents. It welcomed immigrants from Switzerland and elsewhere for decades after the war – the Brintzinghoffers among them.

Prior to the 30 Years War, the surname ‘Brintzing’ dotted the German map like a trail of breadcrumbs pointing to the Kraichgau. In the late 16th and early 17th century, there was a concentration of ‘Brintzing’ families in Gussenstadt, Gingen, Göppingen and Fellback, and it may be that near term the Brintzinghoffers migrated from there, but the surname originates in Switzerland.

The Swiss manage citizenship in a way that’s hugely helpful for finding family origins. There are 3 levels of citizenship – municipal, cantonal and national – and you must have municipal rights to acquire cantonal rights, and you must have both of these to become a Swiss national. Passports and driver’s licenses don’t show your place of birth – they show your ‘Place of Origin’, which is to say they show the place your ancestors first acquired their municipal citizenship – and that can go back centuries.

The ‘Place of Origin’ for those of the surname Brenzikofer is Biel/Beinne, in the canton of Bern. The name Brenzikofer simply means ‘a person from Brenzikofen‘, a medieval town, also in the canton of Bern. The town name itself comes from an old High German personal name Brenz and means, more or less, “Brenz’s outlying farms.”

It is a bit of speculation but I think the documentation – including the relative distribution of this surname in Switzerland and Germany – points to a family origin in Switzerland, a migration to Germany prior to the mid-16th century, and settlement in Sersheim in 1677.

The First Americans

My 8th great-grandfather, Hannß Michel, wasn’t married long the first time. His wife died very quickly and they had no children. Fifteen months after his first wedding, on MAY 11, 1697, he married Birgitta Hëy, the daughter of Hannß Jacob Hëy and together they had 6 children.

Their eldest son was my 7th great-grandfather, Hannß Jörg Brintzighofer. He was baptized on JAN 24, 1698 and later became a wheelwright. We don’t know where Hannß Jörg met and married his first wife, Elisabetha Dorothea – we don’t even know her last name. We do know they were together by 1722 when their eldest son was born, and that they were living 50 miles away in Kupferzell until about 1726 when they returned to Sersheim for the birth of their last 6 children.

On DEC 2, 1736, Elisabetha Dorothea died at the age of 42, one year after the birth of her last child, and Hannß Jörg soon remarried. He and his second wife, Anna Maria Rieger, had 2 daughters in Sersheim.

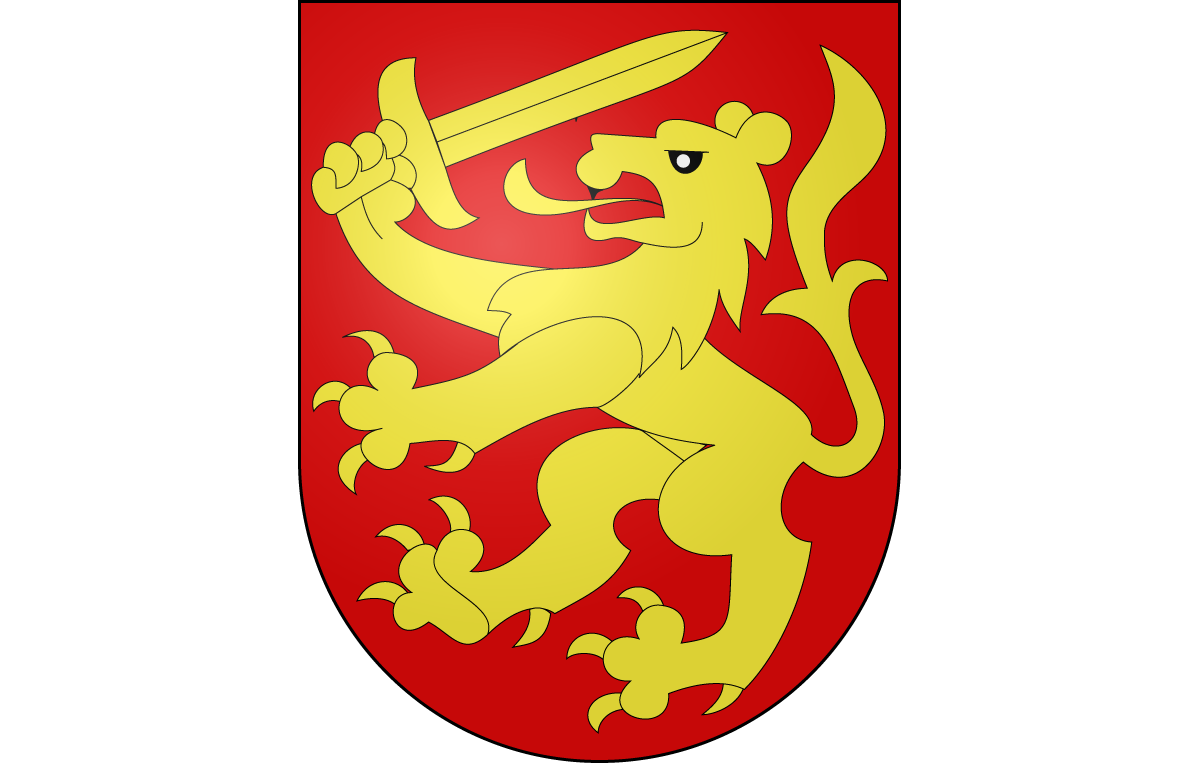

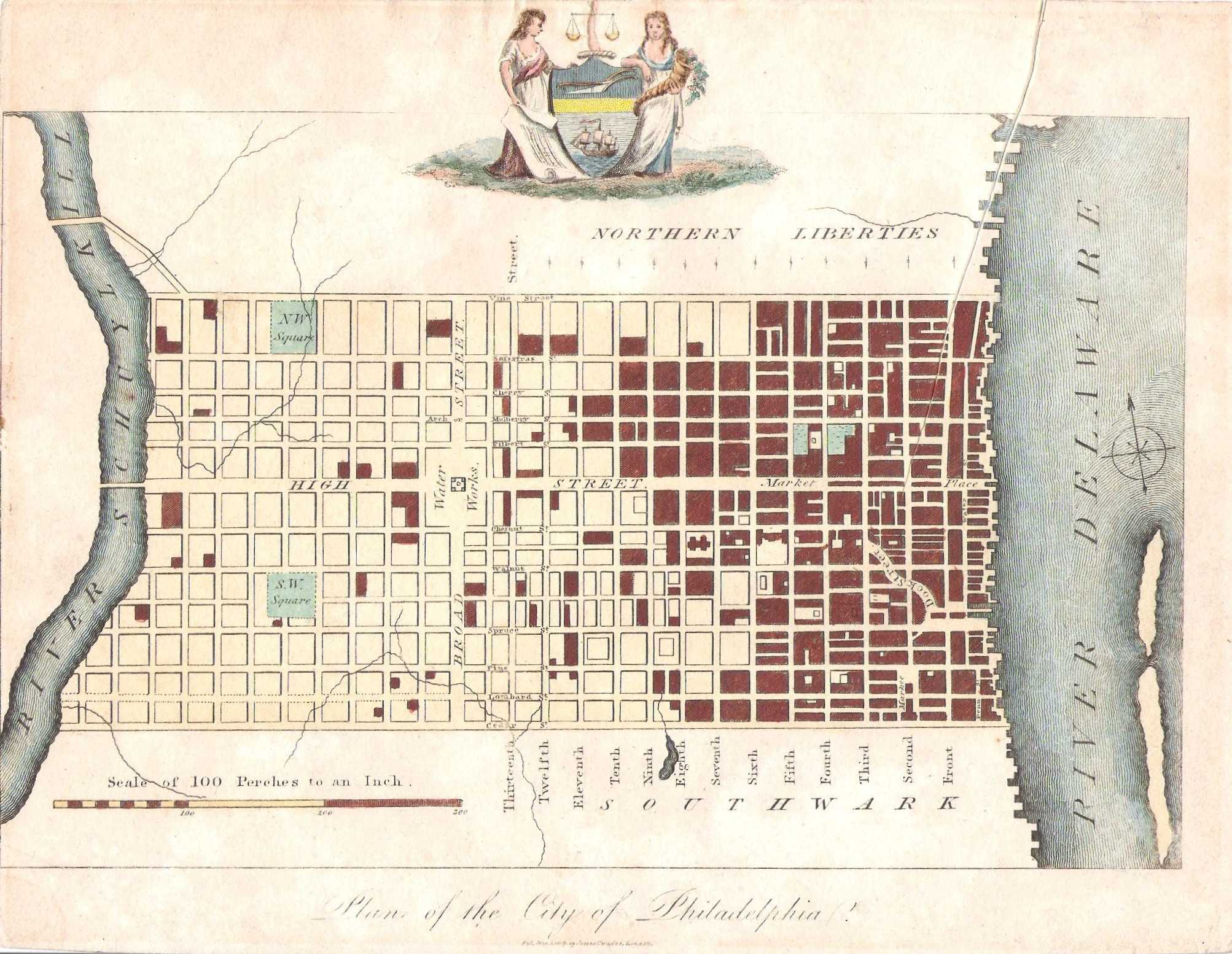

Then in 1752, at the age of 54, Hannß Jörg emigrated to America with his 19 yr old son Hannß Caspar, his wife Anna Maria, and likely his 2 younger daughters. They landed in Philadelphia on SEP 27, 1752.

I know that Caspar went on to have 4 children with Susanna Grob in Lancaster but I don’t know what became of Hannß Jörg after arriving – he basically disappears on the dock. They were the first Brintzinghoffers in America, but they would not be the last. His older children stayed behind in Germany and his great-grandsons by Elisabetha Dorothea, including my 4th great-grandfather, would emigrate later in the century.

The Second Wave

Jörg Melchior Brenzighofer, my 6th great-grandfather, was the eldest son of Hannß Jörg and Elisabetha Dorothea. He was born in Kupferzell on AUG 14, 1722, but raised in Sersheim from at least the age of 5 and, like his father, became a wheelwright.

He married Maria Agnes Reisch, the daughter of Johann Georg Reisch on FEB 4, 1749 at the parish church at Sersheim. I don’t know when they died, I don’t know if they had more children but I know their son Johann Georg Brenzighofer was born and baptized on NOV 24, 1749 and that Johann Georg married Anna Maria Glück, daughter of Johann Conrad Glück, on Valentine’s Day, 1775. They had 11 children.

Their 5th child, my 4th great-grandfather, was Georg Christoph Brenzighofer. He was born on APR 20, 1782, and baptized the next day in Sersheim. He would be the last of my line to live in Germany. He and his eldest brother Jacob Friedrich emigrated to Philadelphia by the time Georg Christoph was 18 or 19 years old.

Georg Christoph Brenzighofer

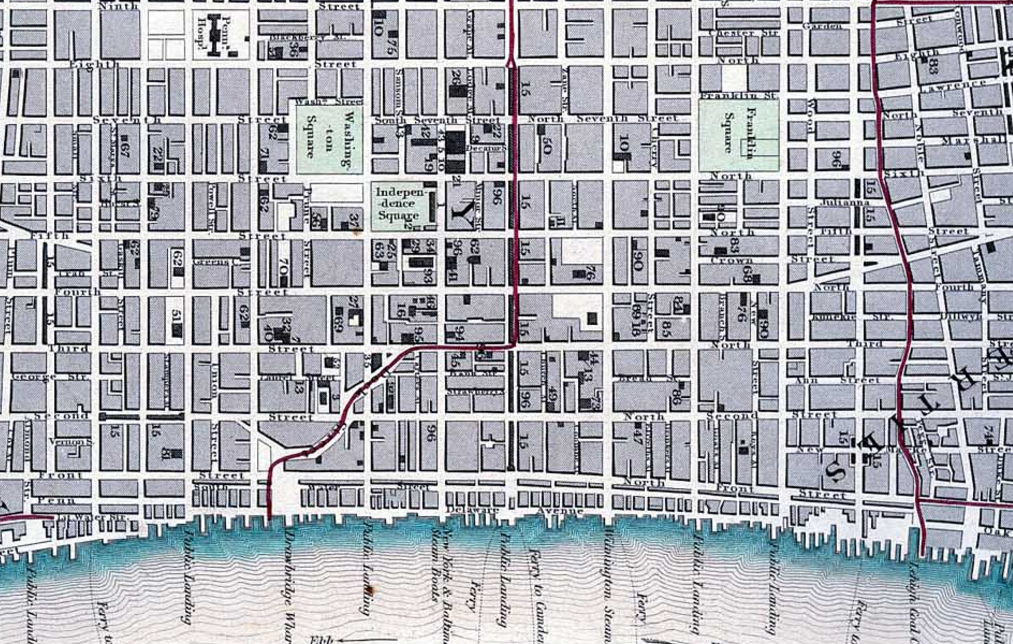

From his listing in the 1806 Philadelphia directory, we know that Jacob Friedrich was a coachmaker at 64 Sassafras Street – it’s now called Race Street because it was used as a racetrack in the 19th century. Georg Christoph may have been an apprentice to his older brother because he doesn’t have his own directory listing until 1810, when we find him coachmaking on his own near 39 Crown St – now called North Lawrence St. They worked briefly as coachmakers, mostly as wheelwrights, and they were the first to use the spelling ‘Brintzinghoffer’ – though it didn’t entirely stick.

On DEC 10, 1807, Georg Christoph ‘Prinzikofer’ married Catherina Meinecke. She was born in Philadelphia to Anna and Gottlieb Meinecke on DEC 22, 1788 and baptized on Christmas Day, probably at Zion Church, where her sister was baptized. We know very little about her parents, except that her father passed away in a yellow fever epidemic in the fall of 1793, when she was 5 years old.

Georg Christoph and Catherina had 7 children.

Their eldest, Elizabeth, was born in 1808 but died as an infant. Anna Margaretha Catharina or ‘Margaret’ was born in 1810 but never married. She lived with her brother Georg Christian, or Charles. Charles was born in 1811 and had 5 children with his wife Mary. He never left Philadelphia. Georg Andrew, or George, was born in 1814 but died at the age of 10.

Their 5th child, my 3rd great-grandfather, was Washington Andrew Brintzinghoffer, born FEB 22, 1816. Wilhelm Heinrich, or Henry, was born in 1818 but died unmarried at the age of 35. The youngest, John, was born in 1823.

The brothers ‘Brentzeghofer’ were both living in the North Mulberry Ward of Philadelphia until at least 1810. Sometime after that, Georg Christoph’s older brother Jacob Friedrich moved to Oley Township in Berks County. ‘Fred’, as he was known, is buried at Friedens Church Cemetery as “Jacob Frederick Brenzenghofer” with his wife and children.

The timing of Georg Christoph’s own death, however, is a mystery. Though cemetery records were kept in Philadelphia from 1803, there is no record of his death. My guess is that he was incapacitated or maybe dead by 1820, and certainly dead by 1824.

He was alive in 1818 when his son Henry was conceived. He had a wheelwright business in the Philadelphia directory at the same address from 1817-1822. But in 1820, Catherina is listed by name in the census and only heads of family were named in that census – all others were counted by age group. So if Georg Christoph were alive and well in 1820, he would be the head of the family and named in the census, but no man of his age is even counted with the family. So something happened to him in 1820.

His son John was born in 1823 and his military paperwork lists Georg Christoph as his father. But in 1823, the business moves to a less central address and in 1824 it disappears from the directory altogether. There is no further trace of Georg Christoph. If he died in this period, as I think he did, then he died during an epidemic when burials were more hastily performed. A ‘fever’ originating at the Schuylkill River struck Philadelphia in 1820 and spread nationwide from there, lasting until 1823. That may explain the missing records but, in truth, I just don’t know.

Catherina died of a stroke on NOV 25, 1876 at the age of 88. She was buried 4 days later in the family plot at Monument Cemetery, Philadelphia. In 1956, when Temple University took over the cemetery, they were able to document – through headstones or records – 2 Meinecke and 5 Brintzinghoffer family members buried in that plot. There were probably others – quite possibly Georg Christoph, but his grave was not marked.

Of the 28,000 bodies removed and reinterred at Lawnview Cemetery in Montgomery County, only 300 of them – those for whom living family members could be found – were reburied with their original headstones. The remaining headstones and statues were dumped in the Delaware River at the foot of the Betsy Ross Bridge to reinforce the shoreline against erosion. The Meineckes and Brinztinghoffers were not among the lucky 300.

Washington Andrew Brintzinghoffer

Washington Andrew Brintzinghoffer was born in Philadelphia in 1816 on FEB 22 – George Washington’s birthday. He’d lost his father by the time he was 8 and his older brother George drown on the 4th of July that same year. His mother, Catherina Brentzenghoffer, never remarried and raised her family at 8 Sassafras Alley in Philadelphia until he was at least 17 years old.

Sassafras Alley ran north to south between Sassafras Street – now called Race Street – and Scheibell’s Alley. Scheibell’s Alley ran east from the east side of 6th street between Race and Vine. Both alleys were torn down in the 1920s to create access for the Ben Franklin Bridge but, essentially, the family lived directly east of Franklin Square Park, under what is now Monument Park and the Ben Franklin on-ramps.

He was probably fluent or conversant in German and may have spoken it at home with his parents. Later in life, when he advertised for a housekeeper, he noted that English or German was preferred, and several of the family’s obituaries were published in German as late as 1898.

He got his feet wet in the tobacco business with the help of an uncle who had an interest in “one of Philadelphia’s leading establishments” but precious little else is known about his time there. His life after Philadelphia, on the other hand, is chronicled minute by minute in the pages of Newark, NJ’s daily newspapers. Like so many of his forefathers, Washington Andrew left his hometown to make his fortune elsewhere.

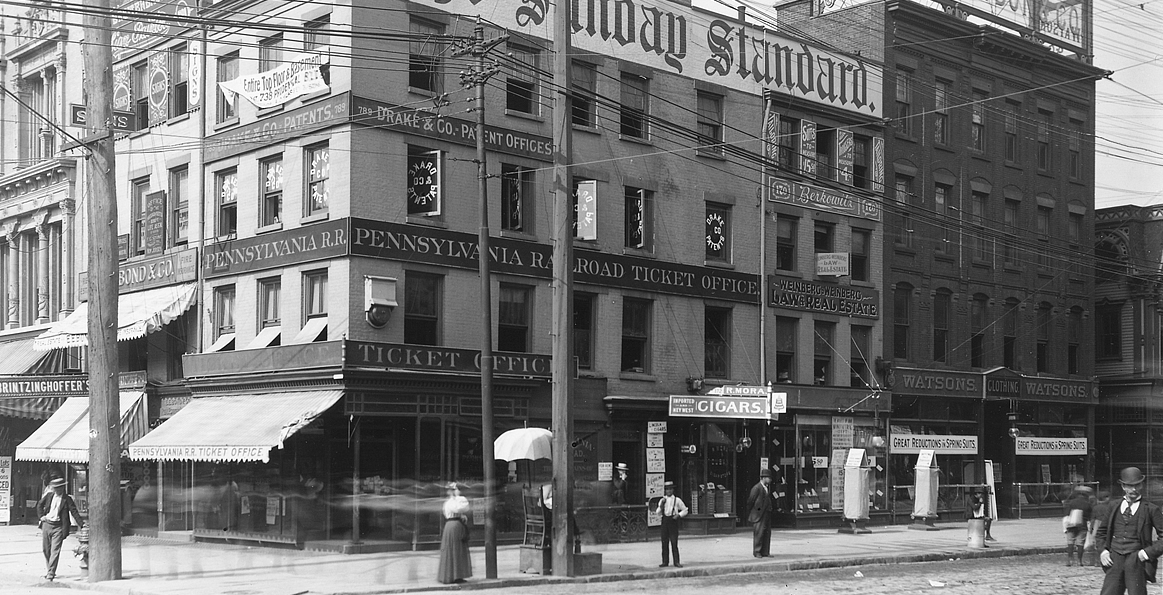

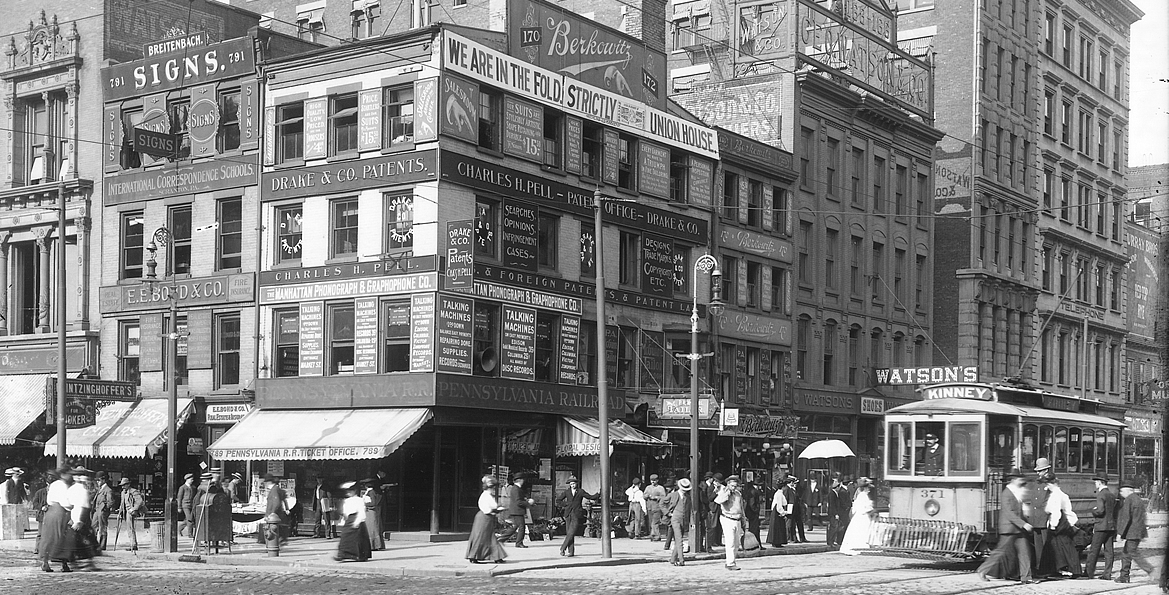

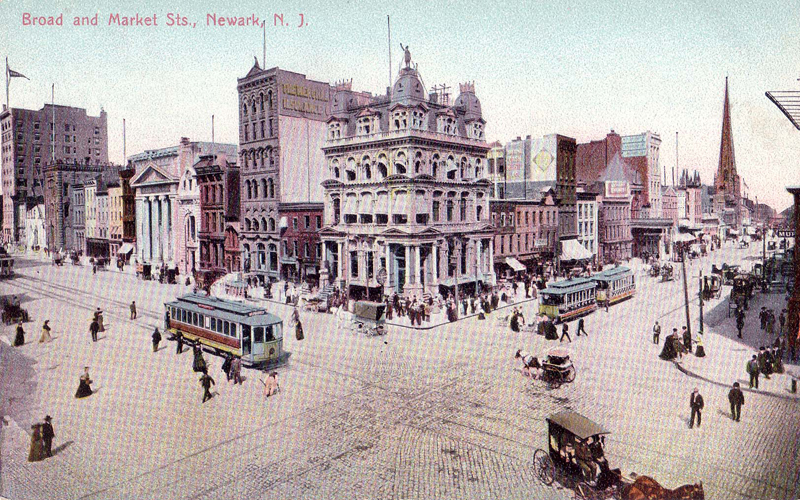

In 1837, at the age of 21, he took a job in Newark, but within a few months decided to found his own cigar & tobacco shop. It was initially located at 356 Broad St but later moved to 374 Broad where it operated until 1868. The first building is gone now, but the later still stands. In 1869, it relocated to 883 Broad St, briefly encompassing 881 as well, and for a time the factory and shop were jointly located there. Neither building remains. After 1887, the factory continued at 883 Broad, but the shop moved to 791 Broad St, near the corner of Broad & Market, and it seems to have stayed there until his death in 1906, but the business did not survive him.

In 1872, 35 years after it’s founding, it was described as employing 50 people with a weekly payroll of $600 and a yearly product of cigars valued at $100,000. In 1882, 45 years after it’s founding, the official history of W.A. Brintzinghoffer & Son was included in a published overview of NJ industries.

W.A. Brintzinghoffer & Son, Manufacturers of Fine Cigars, Jobbers in Leaf, Manufacturer Tobacco, Cigarettes, etc. Nos. 881 and 883 Broad Street – The cigar and tobacco industry of Newark forms a large branch of her manufacturing trade and one of the oldest leading firms in this line is the house of W.A. Brintzinghoffer & Son. In 1837 the senior member founded the establishment on a small amount of capital borrowed at a heavy interest, and so rapid was the increase of the trade he was able to very greatly increase his facilities. The premises occupied are a fine 5-story building 25×75 feet in extent, in which the factory for the manufacture of cigars is located. The first floor is used for the packing office and salesroom, the second for the stock and packing room, the third and fourth for the manufacturing rom and the fifth for drying. Thirty-eight hands find constant work in all the departments of the house. The cigars manufactured by the firm are equal to any manufactured in this country, and among the noted brands made special mention may be of “Brintzinghoffer’s” five-cent straight cigars, which are made up with a clear Havana filler and the best Connecticut wrapper. The stock carried is an extensive one and embraces a large assortment of cigars of favorite brands, smoking and chewing tobacco, smokers’ fancy articles, etc. A large jobbing trade is done and 2 wagons are kept on the road in this business, the sales made being at the rate of $150,000 to $200,000 per annum, and cover the best part of the State of New Jersey. The firm is composed of W.A. Brintzinghoffer and his son Henry, who was admitted to the partnership 3 years ago. The father is a native of the city of Philadelphia, and has served as Alderman of the Third Ward of Newark, where he has been a resident for over 44 years. His son Henry is a native of Newark.

On 19 MAR 1838, a year after founding his company, Washington Andrew married a hometown girl named Margaret Hays in Philadelphia, probably at the German Evangelical Lutheran Church of Saint John – a congregation splintered off from the Zion Lutheran Church. She was the youngest daughter of Catherina Lambert and Addis Hays, Sr, a carpenter in Philadelphia who’s long family history in Burlington and Bergen counties needs a story of it’s own.

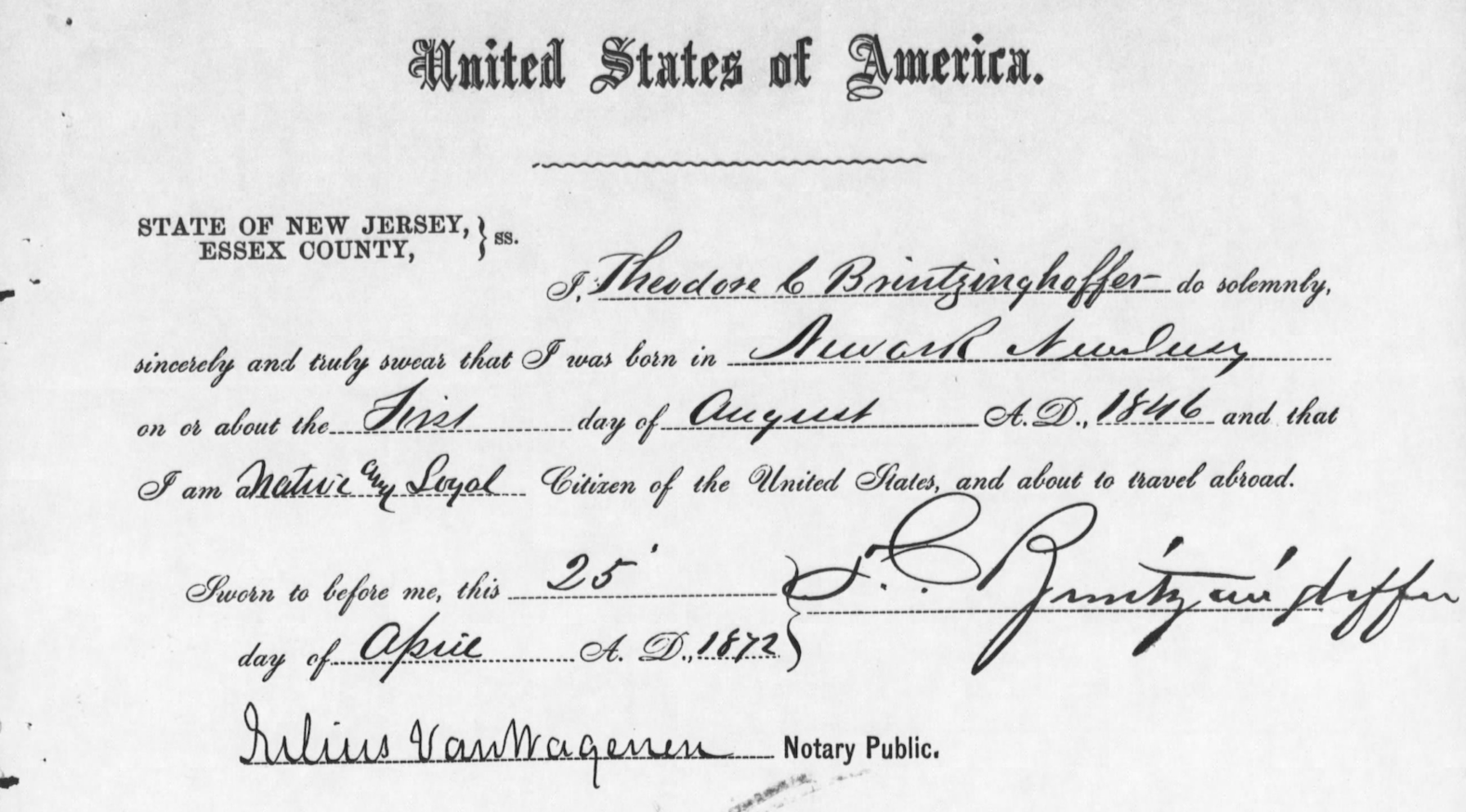

Washington Andrew and Margaret weren’t married long. She died of tuberculosis at the age of 29 on SEP 21, 1847, leaving 3 children behind: Adelaide born in 1838, Margaretha born in 1843, and my 2nd great-grandfather Theodore Canfield Brintzinghoffer born 1 AUG 1846. He was 13 months old when she died.

Two years later, Washington Andrew remarried to Mary Logan Briggs of Philadelphia, at the Moravian Church in New York City. Together, they had 4 boys and 1 girl but only 2 surviving children: Henry born in 1850 and Washington Andrew Jr. born in 1854.

His home address was first recorded in 1838 at 377 Broad St. By 1851, he was at 25 Orchard. From at least 1855 to at least 1868, he lived at 512 Broad across from Washington Park. This last house made the papers for a basement window robbery in MAY of 1855. Apparently, the robbers applied liquid rubber to the glass before breaking it, in order to dampen the noise. Suspicion fell on two Germans seen in the neighborhood that night and the robbers came away with $25 in jewelry and a coat. That same house was robbed again in SEP of 1868. Once again, they broke in through a basement window but this time the thieves came away with nothing.

By 1871, Washington Andrew was living at 21 Clinton Ave. Then, in 1885, he moved and spent 4 years at 37 Clinton Ave. Both homes bordered Lincoln Park, then called South Park, on the fringe of the 3rd Ward. He passed a very short time in 1890 at 1148 Broad St and spent most of the 1890s at 256 Clinton Ave. At the turn of the century, he moved to 900 Broad Street where he later died.

Remarkably, he never purchased a home and not one of the homes he rented is still standing – the majority are now parking lots or empty fields.

The first newspaper mention of Washington Andrew is a lost-and-found ad posted by him in 1851, offering to return a sum of found-money at his shop – but his shop was often in the papers after that. You could place an order for ice there with a 3rd party vendor, or purchase tickets for the next ball or boating excursion. He probably created quite a lot of foot traffic for his business in the process.

The only scandal to ever tarnish his name came on JAN 5, 1854 when he was 37 years old. He and a friend, Matthias Clintock, were racing their horse-drawn sleighs down Broad Street, and Washington Andrew was winning. In an effort to overtake, Matthias collided with a pedestrian who tripped trying to get out of the way. The pedestrian, Beach Vanderpool, was very badly injured by the blades of the sleigh. You’ll be pleased to know Mr. Vanderpool lived to die of something else 30 years later but at the time the op-ed section of the paper was calling for the arrest of the 2 drivers.

Street Racing. There is a point where endurance ceases to be a virtue. Our well disposed, orderly, lawfully minded citizens have arrived at that point and if our city authorities, be they Alderman, City Counsellor, Attorney or Marshal, do not do their duty in preventing fast driving, or at least arresting those horsemen who so openly, and flagrantly, and wickedly, violate the law, the people will take the law into their own hands.

In the decades that followed, Washington Andrew was an upstanding, involved and civic minded citizen. In OCT 1856, he ran for, and won, the 3rd Ward Alderman seat on the Democratic ticket. He served on Newark’s Common Council under Mayor Moses Bigelow from 1857 to 1858 and his cohort of Alderman rewrote Newark’s City Charter. The Council proceedings, including his voting record, were regularly published.

At some point in 1857, a group of Broad St businessmen, including Washington Andrew, formed the Antiquarian Knickerbocker Base Ball Club (AKBBC). Unlike the Knickerbocker Club of New York – who’s regulations established the rules of modern baseball – the AKBBC played old-fashioned base ball, sometimes called town ball. There was no limit to the number of players fielding for a team, the bat looked more like a board or an oar, and the ball itself was made of solid India rubber. There was a ‘ring’, not a diamond, and it had no fixed size. The teams would agree on how big to make it, given the space available to play. Fielders threw the ball directly at the runner and the runner was out when he was hit by the ball – no tagging.

In 1858, when a 130 year old tree was cut down on the corner of Camp and Broad, Washington Andrew had it carved into a large pipe, engraved it, and presented to the Club. AKBBC baseball was played in Newark until about 1865 and at a few exhibitions thereafter.

For the first half of the 1860’s, Washington Andrew sat on the board of the Fireman’s Insurance Company, which was founded in 1855 and existed at least until 1982. It did well enough to build a truly impressive headquarters at the corner of Broad & Market.

He was a charter member of the first Odd Fellows lodge in Newark – Howard Lodge #7 – formed in 1841. He was the Vice President of the Tobacconists National Association in 1866 and, a year later, the Essex Director of the NJ Agricultural Society. He organized conferences in his industry and took a particular interest in supporting the local foster home. His own sons attended Nazareth Hall, an exclusive English and German language Moravian boarding school in Nazareth, PA – and the school published his name as a reputable reference.

He was a charter member of the Road Horse Association and led the procession at its annual parade. He owned several locally famous horses, including one called Prince who won first prize at the Waverly State Fair and sold for $1500 – a bit over $40,000 in today’s money. He was an avid horseman well into his old age, but his skills as a driver might be questionable given one comment in his obituary. (Those of you who know my grandfather, Washington Andrew’s great-grandson, will see an apple falling not far from its tree.)

Mr Brintzinghoffer was never averse to displaying the animals’ good points, and many’s the tale told among local horsemen of the brushes they have had with Mr. Brintzinghoffer on the road.

It would be wrong to talk about Washington Andrew without mentioning his baby brother John who migrated with him to Newark – Brintzinghoffers always seem to travel in pairs. John would have been 14 when the shop was founded and he certainly worked there for most of his life. He was also a Captain with the Columbian Rifles, a unit of the National Guard. Before the Civil War, he organized military parades for the town, with after-parties sometimes hosted by his older brother. During the War, he served as a Captain with Company A, 1st Regiment, and his military service continued with the National Guard well into old age. His paper trail includes service on courts martial, the organization of military balls and parades, pallbearer duties, election as treasurer of the NJ Militia and election as 2nd assistant engineer of the Fire Brigade. He was a member of the Knights of Pythias and he also played ball with the AKBBC.

It’s clear they were very much in each other’s lives and so John’s death – which was likely protracted – probably affected him deeply. John died in 1890 at the age of 66 at the Essex County Asylum for the Insane of organic dementia. Washington Andrew lost his wife Mary Logan Briggs 5 months later after 41 years of marriage.

The last mention I find of his business is from a 1903 article in Tobacco Leaf, Vol. 40 describing a window display for Egyptian Arabs Cigarettes, No. 1 and No.3.

For the past ten days, there has been a display in the window of W.A. Brintzinghoffer’s Sons…which has been drawing big crowds. The centerpiece is a life-size Arab. He sits at ease on a packing case, turns his head and eyes, moves his arms and his mouth and smokes for all the world like a real live man.

Washington Andrew worked into his 90th year. He came in early and stayed late, and was said to be in such good health he never even needed glasses. He operated his business for 69 years, first as W.A. Brintzinghoffer’s, then as W.A. Brintzinghoffer & Son, and finally as W.A. Brintzinghoffer’s Sons.

But, at the end of his life, Washington Andrew had only 2 surviving sons and neither inherited the business. He sold it 12 hours before he died to Jacob Weist of New York.

His namesake, Washington Andrew Jr., made a trip back to Germany at 17, and distinguished himself at the age of 21 by getting the NJ Assembly to incorporate the Triton Boat Club, becoming it’s chairman in 1875 – a promising beginning. But only 4 years later, he was trading on his father’s name in a series of product testimonials. Between 1879 and 1883, he was in ads for Ely’s Cream Balm published as far away as NY, PA and VT, more or less implying that he was his better-known father. He later served prison time for defrauding people by actually claiming to be the owner of the company. He died 9 years after his father in Manhattan.

His son Henry became a partner in the firm in 1879, but his opinion of Henry’s abilities may have been more pragmatic than fatherly. Two years after Washington Andrew’s death, a Madison Avenue cigar dealer named David Reschofsky was bankrupted – 80% of his unsupportable debt came from endorsing an accommodation paper for Henry. Henry defaulted on a debt worth about $109,000 in today’s money and Reschofsky was left holding the bag. He was ruined by it. Henry spent the last 6 years of his life at a Home for Incurables in Philadelphia after suffering paralysis on the left side of his body. He died in 1920 at the age of 70.

Washington Andrew lived to be 91 and died of old age at 4am on 31 MAR 1906. He was buried at Mount Pleasant Cemetery and outlived 5 of his 8 children.

Theodore Canfield Brintzinghoffer

Theodore Canfield Brintzinghoffer was born to Washington Andrew Brintzinghoffer and Margaret Hays on 1 AUG 1846. His mother died when he was still an infant and his father quickly remarried – so his memories of a mother would be of Mary Logan Briggs, his father’s second wife. He had 4 siblings – 2 boys and 2 girls – and the short version of his life is that he was groomed for great things, but never lived to see them.

His formal education was at Nazareth Hall, founded in 1749 for the sons of Moravian parents, but it eventually expanded to accommodate students of other Christian faiths. He was in the class of 1860 and received a classical education in English and German, including board for $50 a quarter. He might also have studied music and painting, but there was an extra charge for that. The halls he walked still stand, but the school itself closed in 1929.

If this school never served any other purpose, it certainly taught some rising Americans the value of order and discipline. At meals the boys had to sit in perfect silence; and when they wished to indicate their wants, they did so, not by using their tongues, but by holding up the hand or so many fingers. The school was divided into “rooms”; each “room” contained only fifteen or eighteen pupils; these pupils were under the constant supervision of a master; and this master, who was generally a theological scholar, was the companion and spiritual adviser of his charges. He joined in all their games, heard them sing their hymns, and was with them when they swam in the “Deep Hole” in the Bushkill River on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons, when they gathered nuts in the forests, and when they sledged in winter in the surrounding country. – History of the Moravian Church by Joseph Edmond Hutton

Attending Nazareth Hall would have allowed Theodore Canfield to rub elbows with the best and brightest and it’s probably through those and his father’s connections that he later became a Freemason at Kane Lodge, #55 in Newark, NJ. He clerked for his father as a young man and became the first ‘Son’ in W.A. Brintzinghoffer & Son in 1871, at the age of 25.

He applied for a passport the following year and from that we get a description of Theodore Canfield himself – 5’6″ tall, a high forehead, dark hair, dark eyes, a round chin, a proportional nose, a fair complexion and a full face.

On 27 MAY 1874, he married Catherine Forman of New Brunswick, NJ. She was 21 at the time, and he was 27. She’d been given a rocky start in life, but a good family name – her Puritan and Dutch ancestors dated back to the 1620’s. Despite his family’s very strong Moravian faith, they married in her faith at the Episcopal Church of St Stephens (1867-1940) on the corner of Clinton and Elizabeth streets.

The wedding ring that Theodore Canfield bought and engraved for Catherine is the same ring that was given by his grandson James to his wife Elizabeth Wiggans in 1942 – and it’s the same ring that I still wear now.

Catherine and Theodore had 2 children together: my great-grandfather Theodore Clarence Brintzinghoffer born 19 SEP 1876, and William Halsey Utter Brintzinghoffer born 7 FEB 1878. ‘Utter’, if you’re wondering, was the married name of Theodore Canfield’s older sister Adelaide – they must have been close.

On New Year’s Eve 1878, Theodore Canfield died suddenly of pneumonia leaving his 25 year old wife with a toddler and an infant. He was buried at Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

Theodore Clarence Brintzinghoffer

Theodore Clarence Brintzinghoffer was 2 years old when his father died suddenly of pneumonia. He would lose his only brother 4 years later in April of 1883 to pseudomembranous croup – an airway obstruction caused by a bacterial infection.

After his father’s death, the family moved from their home at 28 Chestnut St to 452 Washington St in Newark. They lived very briefly with his grandfather, Washington Andrew, when his little brother was ill and his brother died, in fact, at his grandfather’s home. Within 2 years they were back at 452 Washington St, and moved at least 7 more times before 1900.

In 1904, when he was 27 years old, his mother married for the second time and moved to Philadelphia. Theodore Clarence remained in Newark, working as a clerk at his grandfather’s shop on Broad & Market. He took room and board just down the road at 899 Broad St and when the business was sold in MAR of 1906, he found himself without of job. He worked, at least for a time, as a tobacconist at 827 Broad, boarding at 900 Broad – his grandfather’s last address.

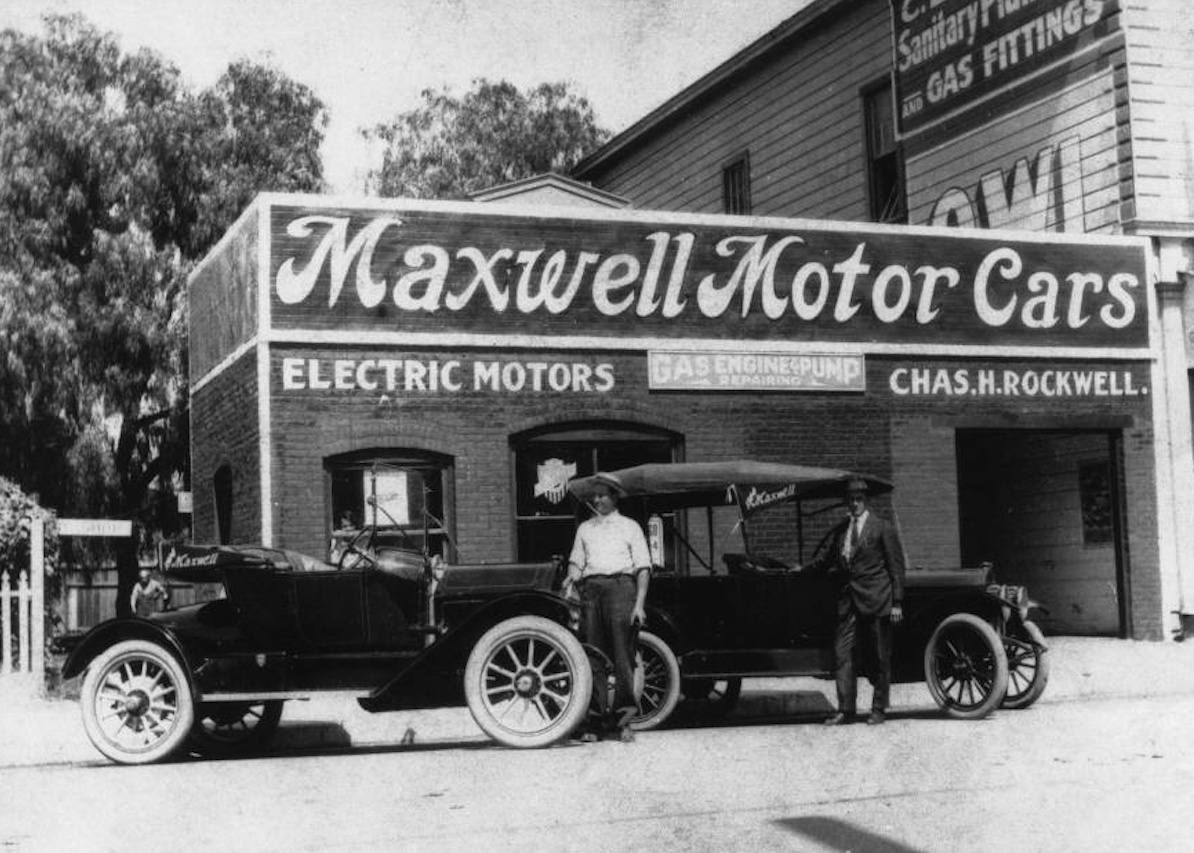

By 1910, he was working as an auditor for the Maxwell Motor Company which was headquartered in Tarrytown, NY. Founded in 1904, it was the first car company to market specifically to women. In 1909, it generated huge publicity by sponsoring the first woman to drive across America.

Theodore Clarence was still living in Tarrytown on 1 JUN 1910 when he married Adelaide Beatrice Hassett at Our Lady of the Valley Catholic Church in Orange, NJ. She was said to tower over his smaller frame and though they were both described as very kind, he was the more mild mannered of the two.

She was 32 years old when they married and he was 33. At the time, women married on average at the age of 21 and men at 25 – so they had a later start than most. She was the daughter of immigrants, a Catholic, and a student of painting at Cooper Union. More importantly, she had at least 10 years experience as a bookkeeper before they married, so they may have met through work.

On the 21 AUG 1912, their eldest son James Henry was born in Orange, NJ. The following year, Theodore Clarence lost his mother to a stroke at the age of 60, and Maxwell Motors relocated the family to Detroit.

Maxwell had joined a partnership of automotive companies in 1910, but by 1913 only Maxwell Motors remained profitable – so the partnership went under and the assets were sold. When the company reorganized, it moved its headquarters to Highland Park, MI where Theodore Clarence eventually became comptroller. For the next 7 years the Brintzinghoffers lived a kind of dual life between 128 Maidstone St in Detroit and 69 Chestnut Street in Orange – the home of Adelaide’s mother.

Their daughter, Catherine Adelaide, was born in Orange, probably at her grandmother’s home, on 6 DEC 1914.

Maxwell Motors continued to market specifically to women and was so strongly aligned with the suffrage movement that in 1914 it hosted suffragettes at its promotional receptions and vowed to hire an equal number of women as men. For a while, it was one of the top 3 car makers alongside GM and Ford, but it over extended itself and collapsed under debt in the post WWI recession. In 1921, Walter Chrysler bought the company and ran it as Maxwell Motors for a time. But, in 1925, he rolled those assets into the newly minted Chrysler Corporation and phased out the Maxwell brand.

Family lore has it that Walter Chrysler offered Theodore Clarence a role in his new company – auditor or treasurer – but that he turned it down because his family wanted to return to NJ. Around 1920, he accepted a job as an accountant with the Sinclair Oil Company, then headquartered in New York City. He worked there for more than 25 years before retiring with a pension in JUN of 1946.

When they first moved back to NJ in 1920, they lived with Adelaide’s mother at 61 Mitchell St in West Orange. Soon after, and certainly by 1924, they purchased a home at 543 Lincoln Ave. Adelaide’s mother and sister joined them there sometime after 1925 and before 1930. His family comfortably survived the depression thanks to his job with Sinclair, but sometime between 1940 and 1944 he sold his home and began an unexplainable financial decline.

At first, they rented a home at 496 Scotland Road and his grandchildren still remember this house. The phone number was OR.6-2867 and Theodore kept a garden there with corn and tomatoes. There were Concord grape vines and Adelaide put up mason jars of jelly every season. There was brick fireplace with a cooking grill, and an enclosed back porch which they used as a pantry. There was a front porch and a terrace in the front yard with many steps down to the street. The kitchen was large and was heated by coal delivered through a chute down into the basement. At night, Adelaide would bank the furnace and in the morning stoke it to make the heat come up. There was a dining room and living room downstairs and 2 bedrooms and a glass sunroom upstairs. It was quite close to the Lackawanna train tracks and you could hear the trains rolling by at all hours. There were paintings by Adelaide covering the walls and they had a television set before almost anyone else. In the yard, were the remains of a garage foundation where they burned leaves and old furniture.

Sometime later, Theodore, his wife and her sister Genevieve rented one half of a duplex on Tremont Ave, owned by the Mahoney’s at 474 Tremont Ave.

Theodore Clarence died there on 26 AUG 1952, at the age of 75, from a bleeding ulcer. He is buried at St. John’s Cemetery in Orange, with his wife Adelaide, her parents, her sister Genevieve and their daughter Catherine. They rest under a single headstone bearing the name of his father-in-law, Patrick Hassett.