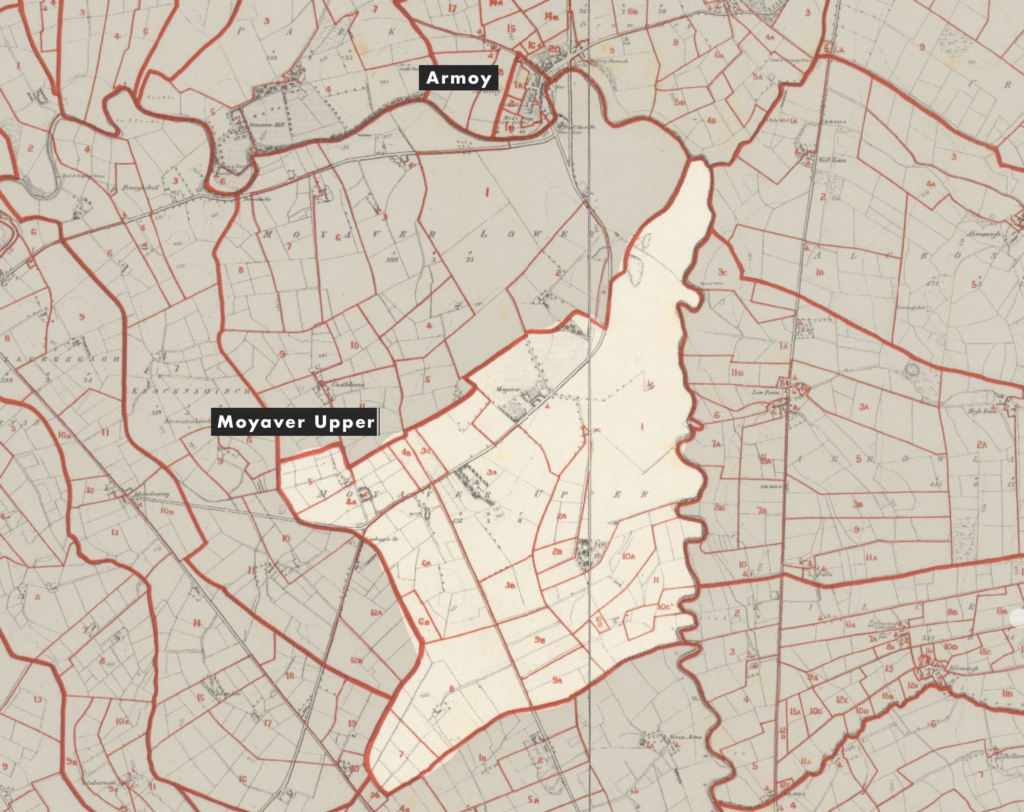

My 3rd great-grandfather, Patrick Scally, was born in Moyaver around 1791. Though his life largely predates Catholic parish registers, we can piece a lot of it together from census and property documents.

An agricultural census shows that his father, Daniel Scally, was working in Moyaver as a farm labourer in 1803. Pension records show that all of Patrick’s children were born in Moyaver in the 1820s. His whole family was still there in the 1841 census and tax records keep him there until his death in 1866.

So it looks as though Patrick Scally lived his whole life within the 574 acres of Moyaver Upper and didn’t have a patch of ground to call his own until he was almost 60 years old. Even then, it was rented land and only made available by extreme tragedy.

I know the Scallys didn’t have a farm prior to the Great Famine. People of all faiths occupying more than 1 acre of land were obliged to pay tax to the Church of Ireland for the provision of social services. The Tithe Applotment books for 1823 and 1837 show NO Scallys, which means the Scallys lived – and feed – off less than 1 acre of land, if they had any land at all.

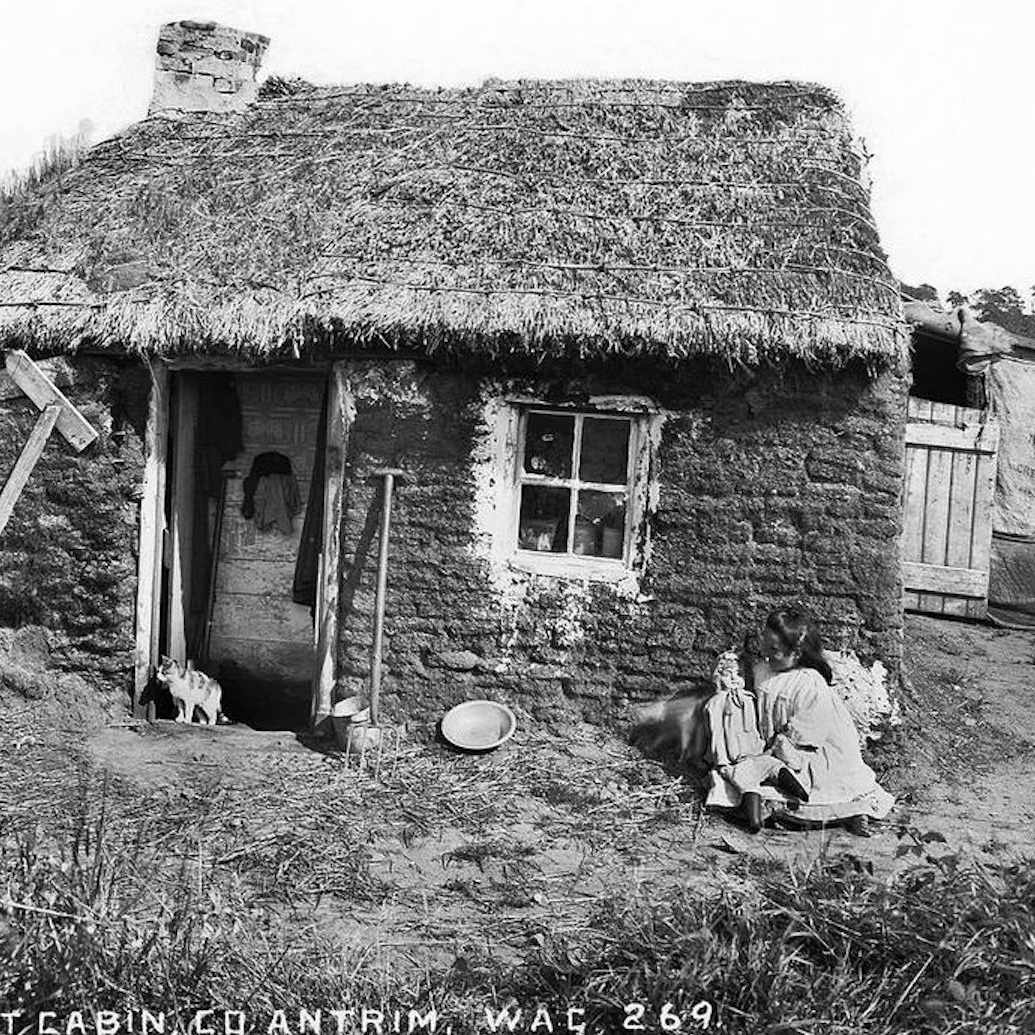

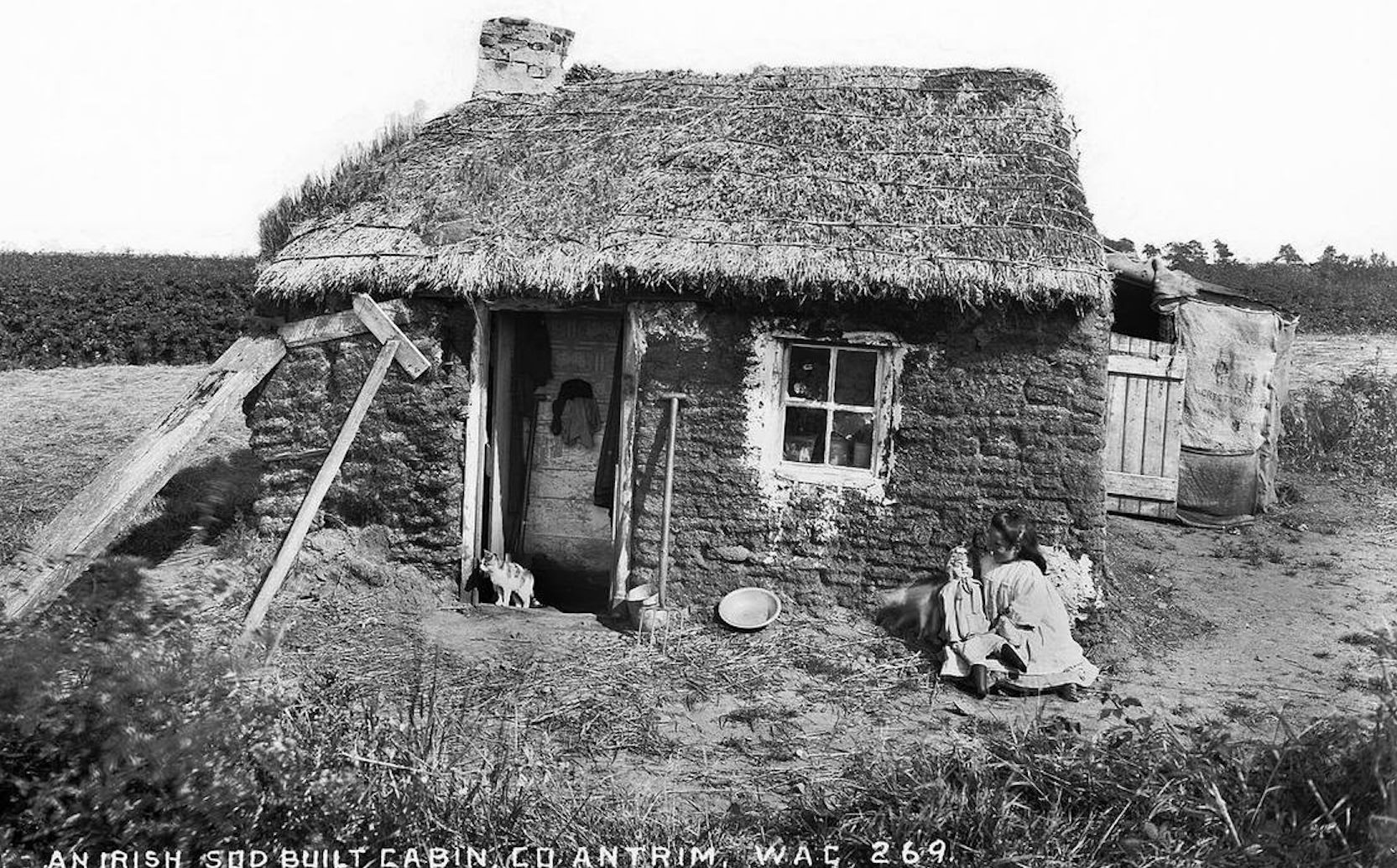

That would put the Scallys squarely in the cottier class. Cottiers typically had a one-room, sod-brick cabin on an acre of land for subsistence farming. They usually paid their rent in labour – as much as 200 days per year. They had very limited rights. Rent could be changed and tenants evicted at almost any time.

More than half of cottiers were completely dependent on the potato – eating an average of 8 pounds per day. If that sounds foolish, it wasn’t. Potatoes are nutritionally dense, easy to grow and yield 17 million calories per acre. Wheat yields just 6 million. Beef just 1 million.

The cottier class was largely wiped out by the Great Famine because it wasn’t a generalized famine – it was a potato blight. So those most dependent on the potato were the most affected by the famine. Other crops had good yields during the famine – bumper crops even – and the rate of food export to England remain relatively unchanged, in spite of widespread starvation. The principle difference was that food was exported under military guard.

The famine lasted for 7 years between 1845-1852 with Antrim losing 15-16% of its population to starvation, disease and emigration. Other counties lost more than 30%. It’s conservatively estimated that 1 million people starved to death country-wide but that figure doesn’t take into account the death rates of Irish fleeing the famine. Emigrating Irish died onboard the coffin ships at an average rate of 20%. Some northern routes were as high as 50%.

So why did Patrick’s family survive when others did not? I don’t know. Maybe he chose to plant some part of his acre with oats or flax, instead of potatoes. That would have given him a viable food source and good seed for planting. Maybe he had a secondary income from spinning, smithing or weaving. I’d love to know, but I just don’t.

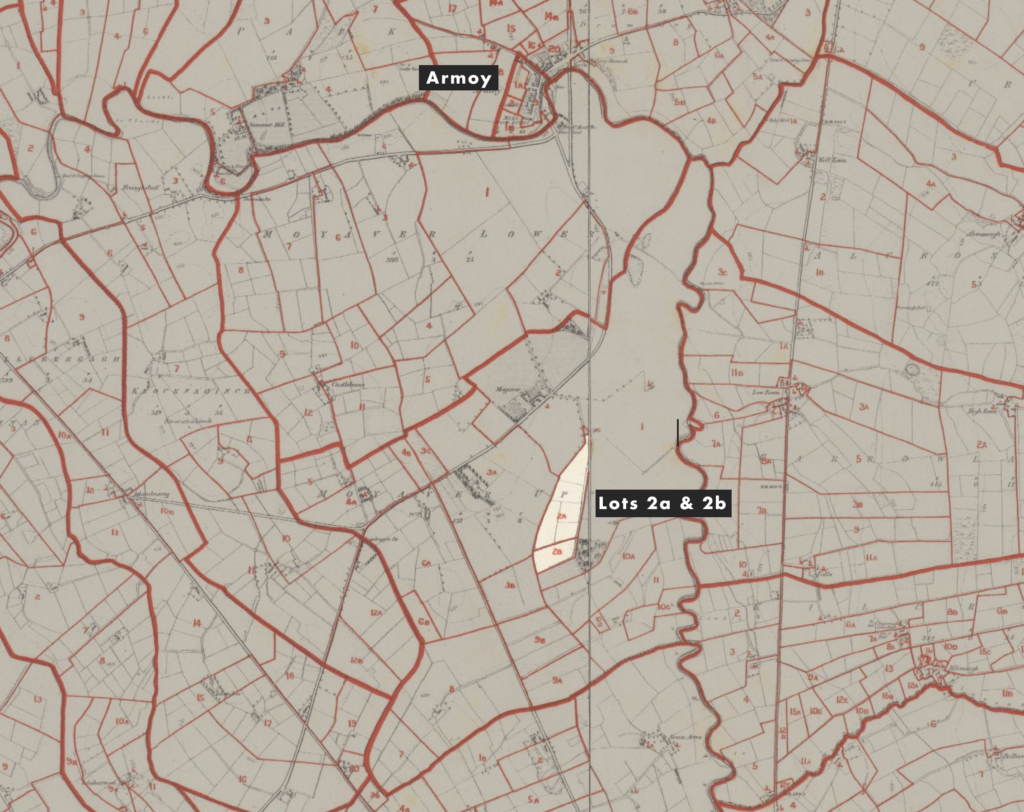

What I do know is that the famine made land available. As people died, fled or were evicted, land became available. The first record I have of Patrick leasing a farm is from near the end of the famine when he shows up in the 1851 Householder Index for Moyaver. He would have been 60 years old at the time.

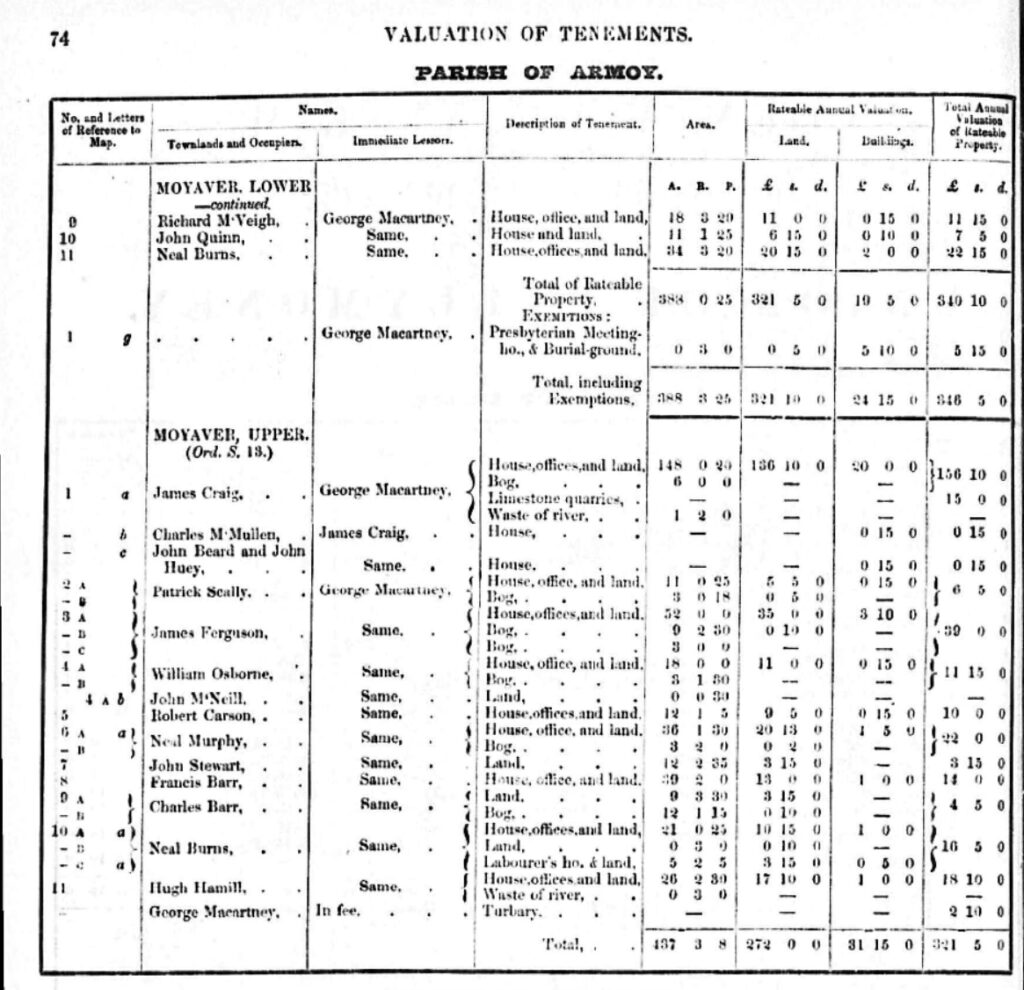

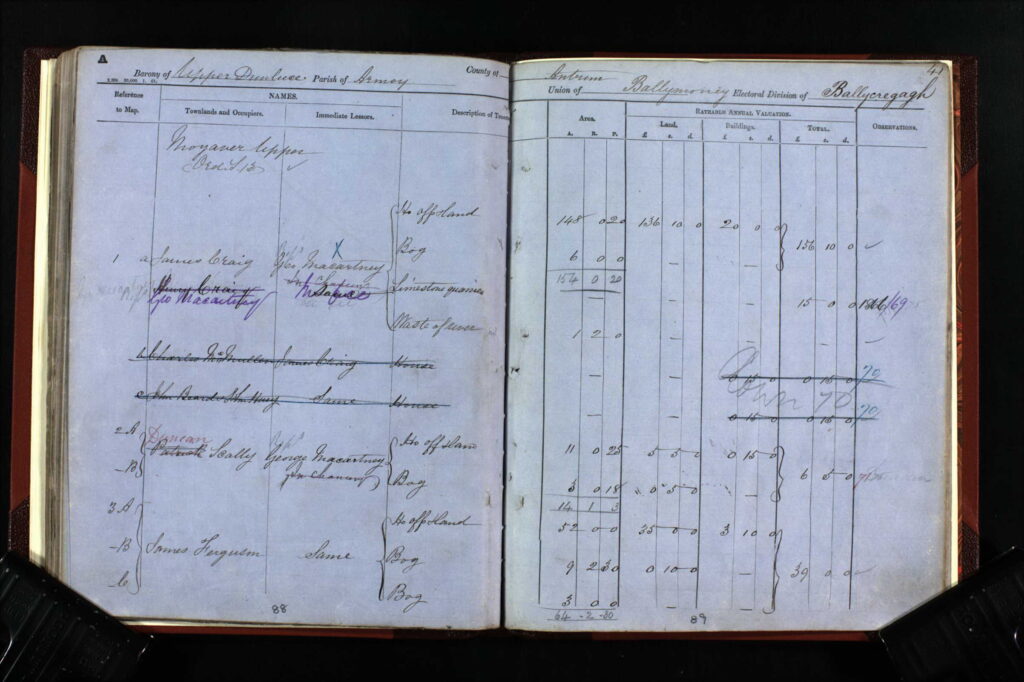

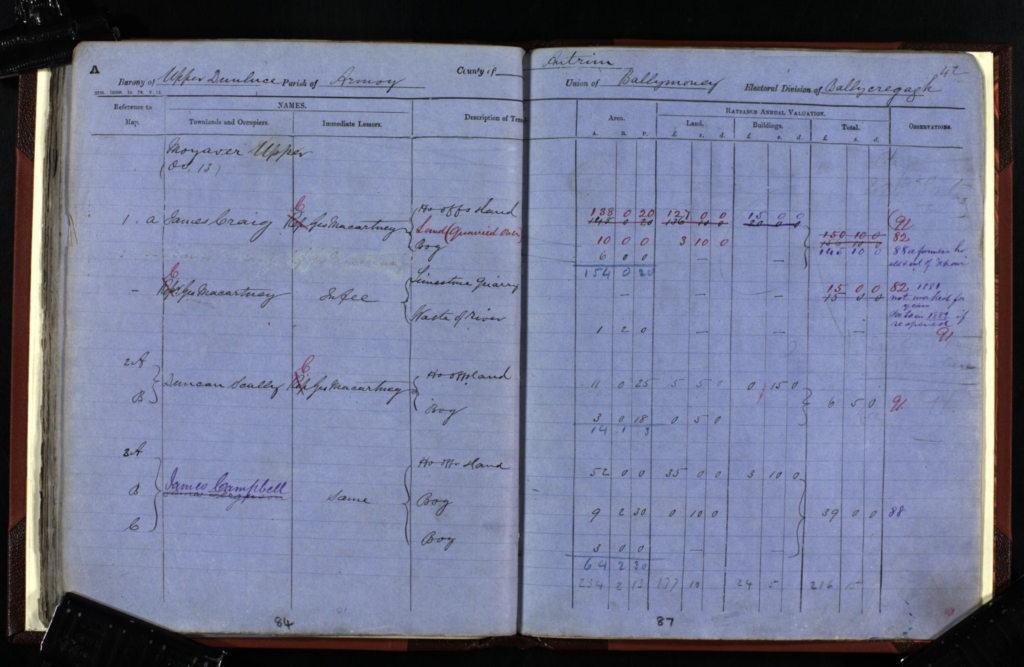

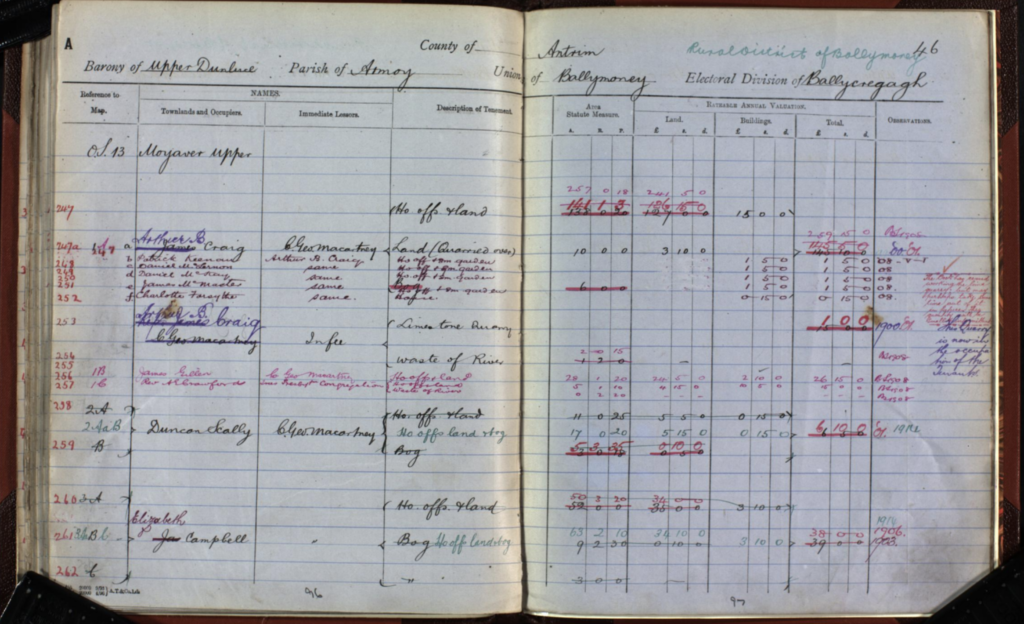

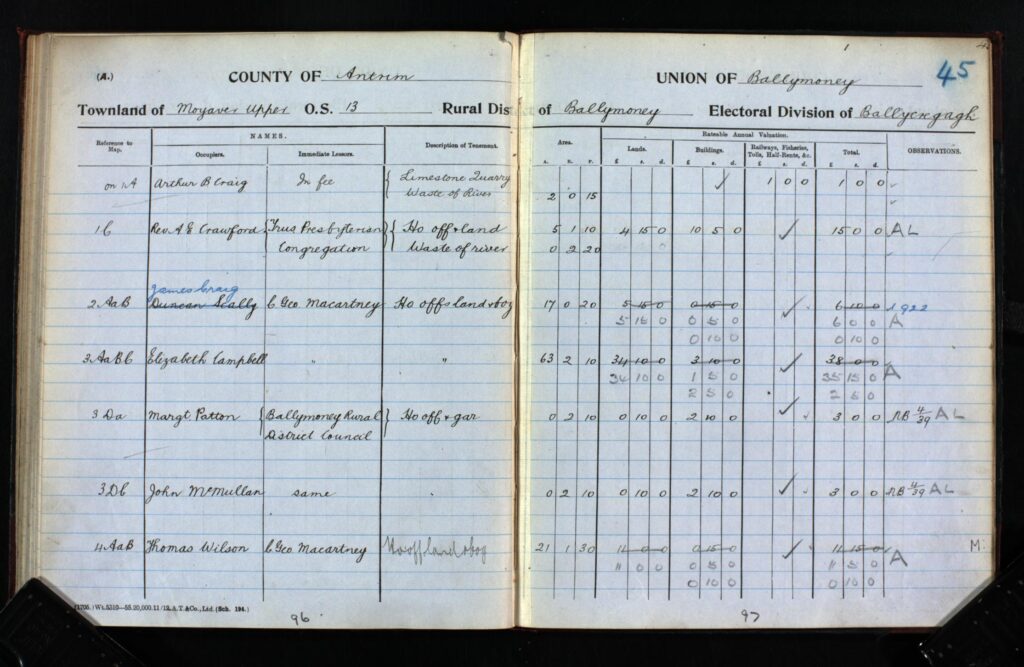

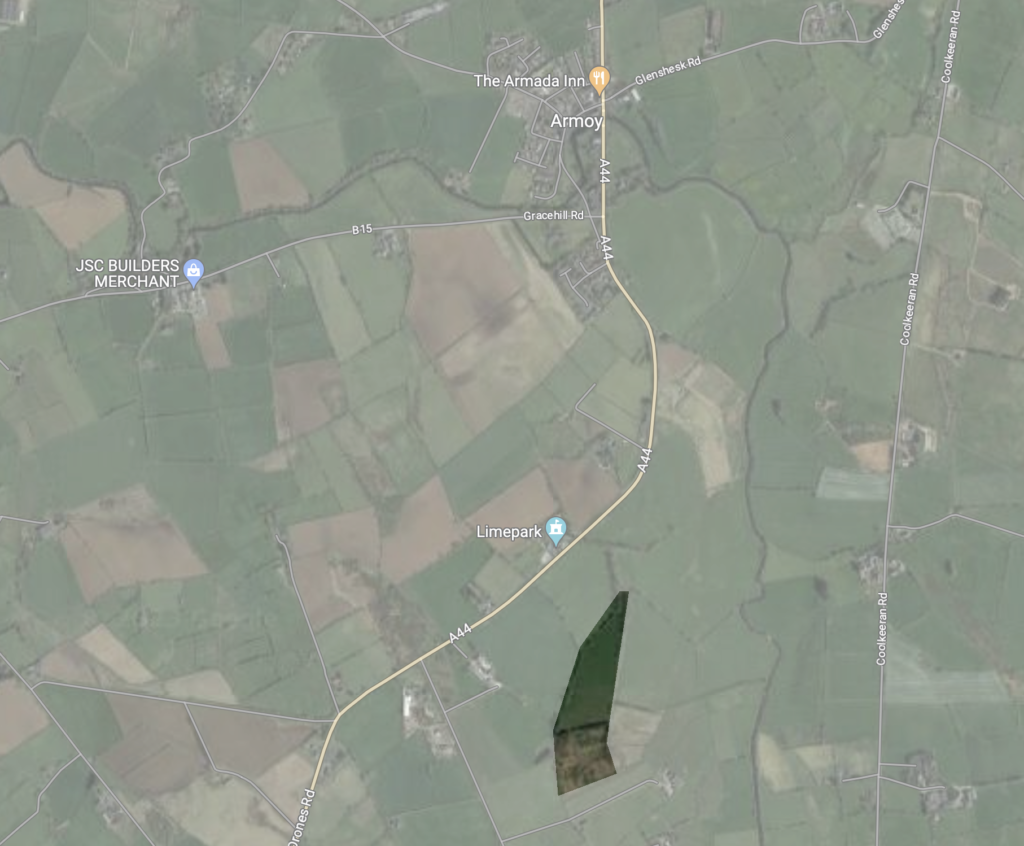

According to the 1861 Griffith’s Valuation and all subsequent Valuation Revisions, Patrick Scally’s leasehold was for a farm on Lots 2a & 2b. It came with a house and 15.8 acres of land, including a bog. The census record tell us the house had stone walls, a thatched roof, 2 windows in the front, and between 2 to 4 rooms. It was categorized as a 3rd class structure, but nothing of it survives there now – but the field boundaries are unchanged.

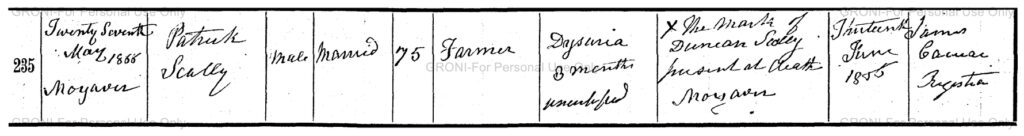

When Patrick died of dysuria in 1866, the lease passed to his son, my 3rd great-uncle, Duncan. It passed out the family entirely when Duncan died unmarried, without heirs, in 1916. The Craigs, just across the road at Limepark, took over the lease.