Elizabeth Irene Wiggans ← James Wiggans (Elizabeth Rooney) ← John Wiggans (Sarah McIntyre) ← John Wiggans (Dinah Baker) ← James Wiggans ( Alice Sumner) ← John Wiggans (Nancy) ← James Wiggans (Jane Hindle)

The Wiggans surname was brought to England by the Normans after the Battle of Hastings in 1066. It is derived from the personal name “Wuicon” or Wigand – meaning high or noble – and it was first recorded in the Domesday Book as “Wighen” in 1086, in Cambridge. Wiggans is the patronymic form of the name, as in “son of Wigand”.

The earliest verified Wiggans traced on my family tree is my 6th great-grandfather, James Wiggans, born around 1730. He was married to a woman named Jane, probably Jane Hindle. More documentation is needed but it’s likely I can trace the Wiggans/Wygan family a further 5 generations back to James Wygan born around 1520 in Chorley, Lancashire and, in fact, there are several farmsteads named Wiggans that show up in the record of the area.

What I do know is that James, my 6th great-grandfather, lived in Eccleston and was described a yeoman – an archaic term for a man holding and cultivating a small landed estate – a freeholder. Most land in England was held by lease, so if James owned the land, he would have been better off than most.

His son John was born in Eccleston on the 15th of May, 1756 and baptized at St. Michael and All Angels in Croston on January 12th, 1759. He was a husbandman – an archaic term for a farmer. The baptismal records of his children tell us that his wife’s name was Nancy and that they probably married sometime around 1780, more or less.

But the story comes into sharper focus when we look at their son James.

Sarscough

James was born on May 9th and baptized on May 31st, 1786 at St John’s in Preston. He was the second James born to John and Nancy, so the first – born a few years before in Alton – must have died as an infant. In the census, James repeatedly said his birthplace was Grimsargh – but it wasn’t. He was actually born in Ulnes Walton and his younger brother Thomas was born in Grimsargh. He had to rely on memory, we can check the parish register.

He married Alice Sumner on February 27th, 1810 at St. Mary the Virgin, in Eccleston. She was born in Euxton to Thomas and Ann Sumner and baptized at St. Andrew’s in Leyland on the 19th of October, 1787.

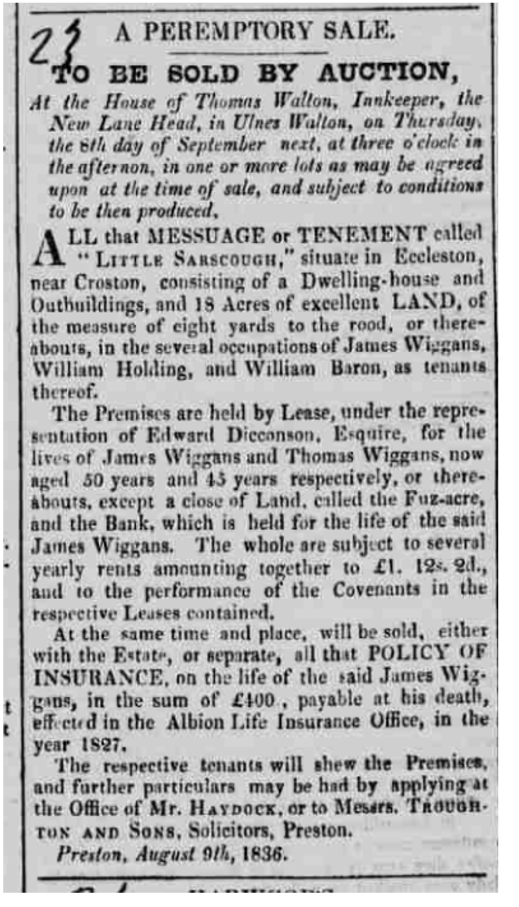

From at least August of 1836, and probably long before, James and his brother Thomas had a leasehold on a property called “Little Sarscough.” There is no Little Sarscough on the map now but we know it was in Eccleston, near Croston, between New Lane and Row Moor – which places it solidly in Ulnes Walton.

They didn’t own the property, they owned a lifelong right to use the property – so long as they paid their rent. In addition, James held a life lease in his own name on 2 other plots – Fuz-acre and the Bank. We know all this because the property was auctioned off in 1836, along with a life insurance policy on the 50 year old James. Essentially, it offered the new buyer a guarantee of money, in lieu of rent, should James unexpectedly die.

James described himself as a gardener (1841), a nurseryman (1851) and sometimes a farmer. But he must have also been an ambitious man, because he progressively enlarged his holdings over the years. In 1836 – he was 1 of 3 tenants on 18 acres. By 1851, he was working 36 acres himself and he largely held that land through the end of his very long life.

Beginning in the early 1840s and continuing through at least the late 1850s, James competed in the Leyland, Eccleston, Penwortham, Haigh, Preston and Ormskirk Floral and Horticultural shows. For 20 years straight, year after year, each and every fall, he appeared in the Preston Chronicle winning prizes for his floral arrangements – most especially for his dahlias. He occasionally competed in vegetables, once winning for the heaviest onion, and once for the best 2 stalks of red celery. There are too many clippings to included them all here. I found 23 articles without trying very hard to find anything at all.

James and Alice finished their days at Sarscough. Alice lived to be 85 years old and was buried October 24th,1871 at St. Andrews. James outlived her by a year, passing away at the age of 86, and was buried beside her on May 17th, 1872.

The Last Farmer

John was born in Eccleston on September 24th, 1810 to James and Alice Wiggans. He was baptized 4 days later at St. Mary the Virgin, and the oldest of perhaps 11 or 12 siblings. This John was the last to make his living off the land, but he calls himself a farm labourer, not a yeoman, not a husbandman. So that implies he was never in possession of a leasehold.

As the oldest son, he was probably working at his father’s farm in Sarscough and hoping to take on the property after his father’s death. His father’s lease was for life only but landlords could and did contract with continuing generations. Unfortunately, John died 2 years before his father, at the age of 59, and did not live to work his own land.

Like James, John competed in local agricultural shows. He didn’t win the top prize as often as his father but there was probably more competition in the vegetable categories he entered. He won 3rd prize for a Mangelwurzel – I had to Google that one, it’s a beet – and 2nd prize for a stand of white celery.

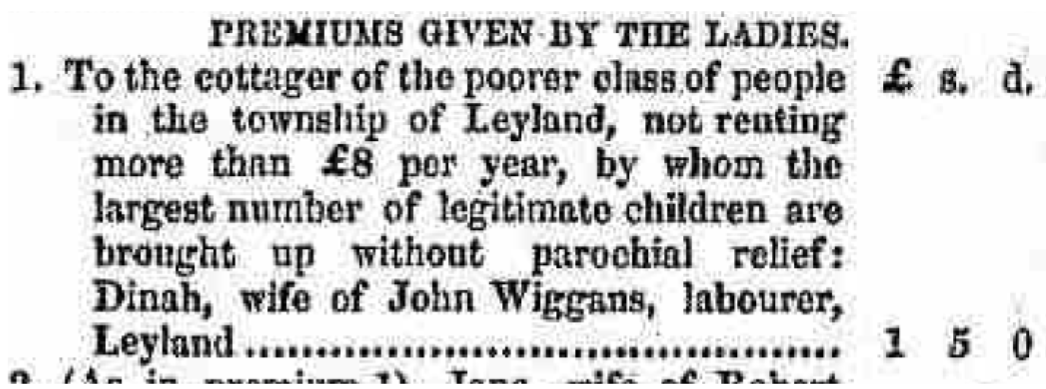

My favorite award went to neither James nor John, but to Dinah Baker – John’s wife. She won a prize for the mother of the “poorer classes” raising the largest number of legitimate children without resorting to parish welfare. Good on you, Dinah!

John married Dinah on October 4th, 1831 at St. Mary the Virgin and together they had at least 10 children, eight of which entered the mill. In mid-century, the new infrastructure of canals and railroads combined with industrial innovations in textile manufacturing and transformed the Lancashire economy. Only 2 of their children did not go into the textile industry, one became a dressmaker, the other a gardener like his grandfather.

John died on the 4th of August, 1870, and was buried 2 days later at St. Andrews. His wife Dinah survived him by 9 years.

The Clamper

John Wiggans was born the son of John Wiggans (1810) and Dinah Baker and was baptized at St. Andrew’s in Leyland on May 20, 1848 – the church pictured at the top of this article.

By the age of 12, he was working in the Leyland bleachworks – which started out as a crofters in the 1790s and first took off under the name Fletcher’s, and later as John Stanning & Sons Bleachworks.

He may have been as young as 6 when he started working there. We don’t know what his job was at that time, but children were frequently employed to run under machines to remove lint which would otherwise have been a fire hazard. The machines would have been operational during this process, and accidents can and did happen. Nothing much changed in 1870 when the government made education compulsory to the age of 12. The mills simply hired children to work the after-school shift.

John may have met his wife Sarah McIntyre in the bleachworks – they were both cotton bleachers around the time of their marriage. She was a Scot from Lanarkshire, formerly a lace tambourer, and they married at St. Andrews on the 14th of March 1868. He was just 19 and she was 24, but claimed to be 22.

They moved in with his parents, John and Dinah, and stayed on to live with his mother after she was widowed in 1870 at 91 Towngate in Leyland, very near the factory.

Looking at the birthplace of his children, we know he left Leyland and moved to Chorley in 1875 or 1876. By 1881, age 32, he had 3 children and they were living on their own at 19 Eaves Lane.

There were too many mills in Chorley to take a guess about where he worked but we do know he was a finisher at a calico factory. There were a number of finishing techniques applied to cotton after it was dyed – some enzymatic, some mechanical.

By the age of 42, he was a clamper at a bleachworks and I haven’t been able to sort out exactly what that was – although it may have been the application of clamps to create patterns in the dying process. I do know it was considered a dangerous job even by the government of the time because they investigated the employment of boys in clamp rooms where high temperatures and lack of ventilation were a known hazard.

John lost his wife in 1909 and in 1911 he was still living with his 29 year old son James – a mangler at the bleachworks – and his 27 year old daughter Dinah Baker Wiggans – a lace tambourer. His son James emigrated to America in 1912, and John lived out his days in Chorley, dying at age 72, at 87 Bolton St. His body was brought home to Leyland for burial at St. Andrews on the 10th of March, 1921.

The Last Englishman

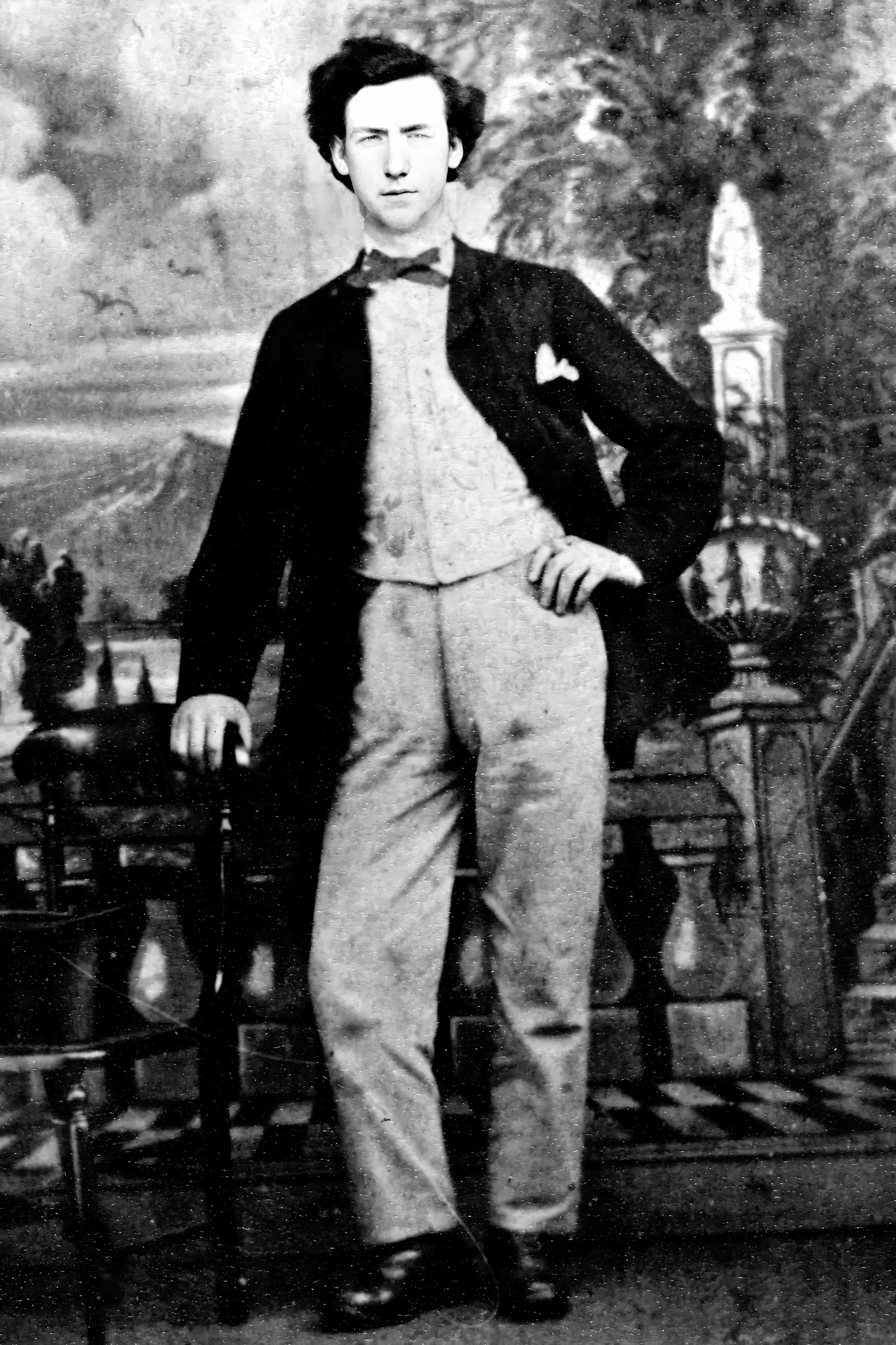

James Wiggans was born to John Wiggans (1848) and Sarah McIntyre on August 1st, 1881 at 19 Eaves Lane in Chorley.

He was their 4th surviving child. Their first, Isabella, had died in infancy and that may explain why they waited until the 6th of November to baptize him at St. James Church. There were 10 siblings altogether but only 5, and maybe fewer, lived into adulthood.

We know that he was still in school at the age of 8 – school was compulsory by then for children under 12. But we don’t know if he was working after school.

Sometime before the age of 19, he followed his father into the bleachworks as a mangler – a mangler is a roll press machine operator – and he stayed on in that profession until he left England more than 10 years later.

There is a family myth that James had a ticket to sail on the Titanic but missed the boat because he was watching a horse race. That story is not entirely untrue – just very, very embellished.

The Titanic sank on April 15, 1912, and James was booked to sail on the Baltic just a few weeks later – on the 23rd of May. He did, in fact, miss the Baltic and his name appears on the manifest with a line through it and a notation of NOB – Not On Board. He actually left for America a week later on the Cedric, departing on May 30th, and arriving in New York on June 8th. He passed through immigration at Ellis Island.

We can’t know for sure if his love of the ponies delayed his departure but he did take his daughters to the races every Sunday so we can be certain he had a real fondness for the track.

His immigration record tells us he was 29 years old, literate, of the English race and born in Chorley. He was 5′ 8.5″ with light brown hair and blue eyes. There was a vaccination mark on his left arm and a burn mark on his right leg. That would be a common injury at a bleachworks. His father, his next of kin, was living at 136 Eaves Lane, Chorley and he was heading to the home of his friend James McIntyre’s at 23 Claremont in Jersey City. He later roomed with his friend Frank Redden at 76 Peshine Avenue and, after settling into a job, he sent for his childhood sweetheart, Elizabeth Rooney.

She was a Chorley girl who – along with her 2 sisters – followed James to America. A year after arriving, he married Elizabeth at Blessed Sacrament in Newark, NJ on the 6th of April, 1913.

His WWI draft record categorizes him a declarant alien – a person who had officially declared his intention to become an American citizen before a court of record. Naturalization was generally a two-step process that took about 5 years to complete. After living in the US for 2 years, an alien could file a declaration of intent. Then, after 3 further years, he could petition for naturalization. James himself was naturalized on the 26th of July, 1921 at the Court of Essex County, which means he had probably become a declarant alien around the time of his draft registration.

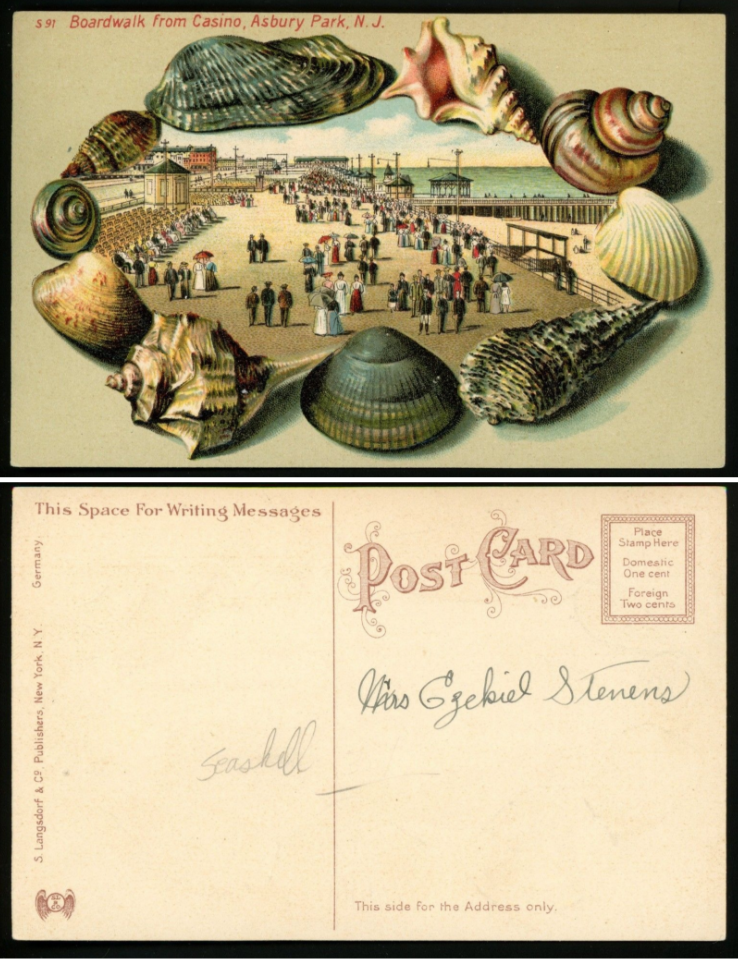

His machine experience in the Chorley bleachworks served him well in America. He started as a die presser in 1914, and by 1918 was an assistant foreman with S. Langsdorf & Company at 72 Spring Street in Manhattan – a German postcard publisher.

By 1920, he was working as a pressman in a celluloid factory. Newark had become the celluloid manufacturing capital of the world, and celluloid had become the go-to material for billiard balls, cuffs, collars, brushes, napkin rings, and anything that might have otherwise been made from tortoise shell or bone before the invention of plastic. Unfortunately, celluloid was also highly explosive. Over a 36 year period, there were 39 fires/explosions, 9 deaths and 39 injuries in just the Newark factory alone.

By degrees the plastics industry shifted to less flammable materials and on the eve of WWII James was working as a dye mixer for the E. I. DuPont de Nemours Company on Schuyler Ave, near North Arlington in Hudson, NJ. He finished his career with DuPont and retired in 1950.

By all accounts, James lived a very happy life with his wife and 2 daughters on 290 Peshine Ave in Newark until 1932 when he suddenly lost both his wife and his sister-in-law in a matter of weeks over the summer. He soldiered on raising his daughters alone through the Great Depression and by all accounts was a loving and wonderful father.

He lived to see at least one great-grandchild born and passed away at the age of 83 on the 16th of January, 1965 at St. Mary’s Hospital, in Orange, NJ. He was buried beside his wife Elizabeth in Holy Cross Cemetery on the 20th of January.