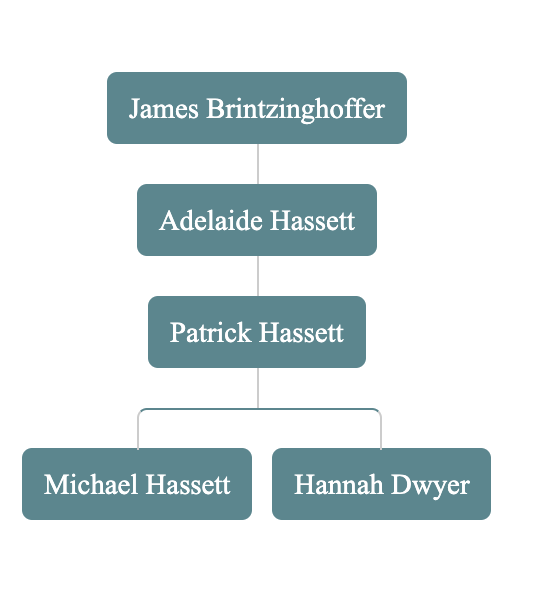

Patrick Hassett, my 2nd great-grandfather, was born around 1840 to Michael Hassett and Hannah Dwyer in County Clare, Ireland. We can piece that together from a handful of American church records, but we don’t know which of the 46 parishes he called home. Records began too recently to include him in 24 of those parishes and there is no trace of him in the other 22. Odds are, based on the prevalence of the surnames Dwyer and Hassett, he’s from somewhere near Killaloe.

The population of Clare doubled in the 50 years prior to his birth. It peaked the year after he was born in 1841 – 286,394 souls. By the time he was 10, 50,000 of them would be dead from famine, or the diseases that spread with it. During the worst years, a third of the population was on relief and the rate of forcible transportation doubled, mostly for theft of food. Seventy-five percent, Patrick included, were illiterate and by the time he left for America, one quarter of Clare’s population had already emigrated.

Immigration

I believe Patrick crossed on the Harvest Queen from Liverpool to New York City – probably via Queenstown / Cobh – and arrived in April of 1860.

The Harvest Queen was an American packet ship of the Black Ball line, built in 1854, and principally designed to carry mail and passengers. Wind and weather dictated the journey, but a westbound passage averaged 35 days, and could take as long as 57. A fix amount of staples would be provided – oatmeal, rice, molasses, tea – but the passengers had to cook it themselves, and passengers in steerage had to provide their own bedding. They would eat, sleep and pass the day in the same interior space, which they often shared with cargo.

Civil War

He may have landed in New York looking for sanctuary but Patrick found a country on the brink of civil war. Within 6 months of his arrival, Lincoln was elected to the presidency without even appearing on the ballot in the deep south. Just before Christmas, South Carolina seceded from the Union and demanded that the US Army abandon its post in Charleston Harbor. A struggle to resupply Fort Sumpter ensued and when Lincoln was inaugurated on MAR 6, he notified the governor of South Carolina that he would be sending ships. The Confederates replied with an ultimatum – Evacuate! The Battle of Fort Sumpter lasted 34 hours. Outmanned and outgunned, US forces surrendered Fort Sumpter on APR 14. Lincoln immediately called for 75,000 volunteers.

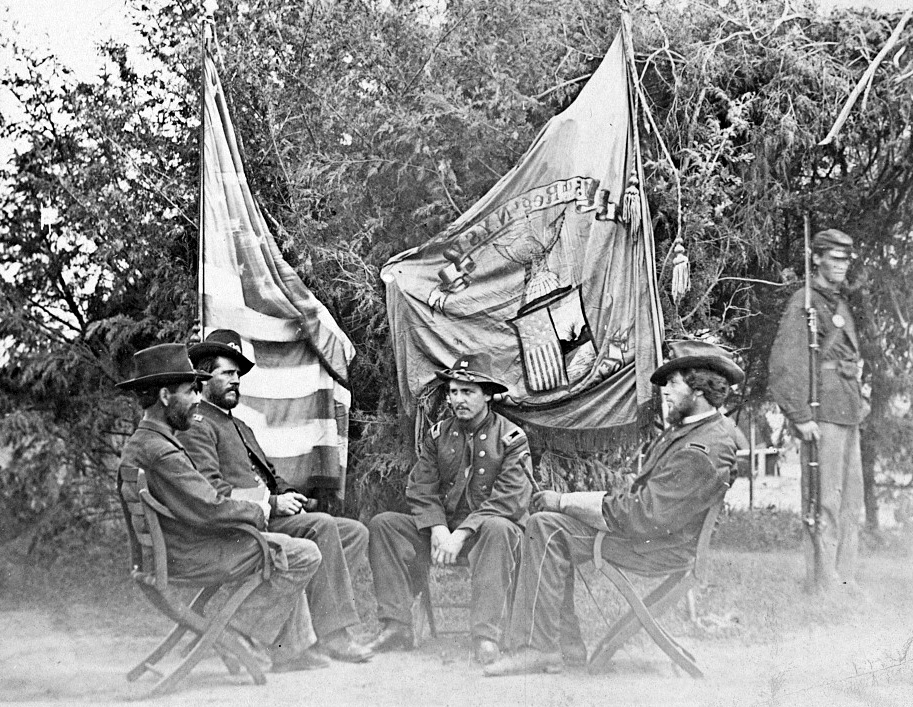

9th MAY 1861 – Enlistment

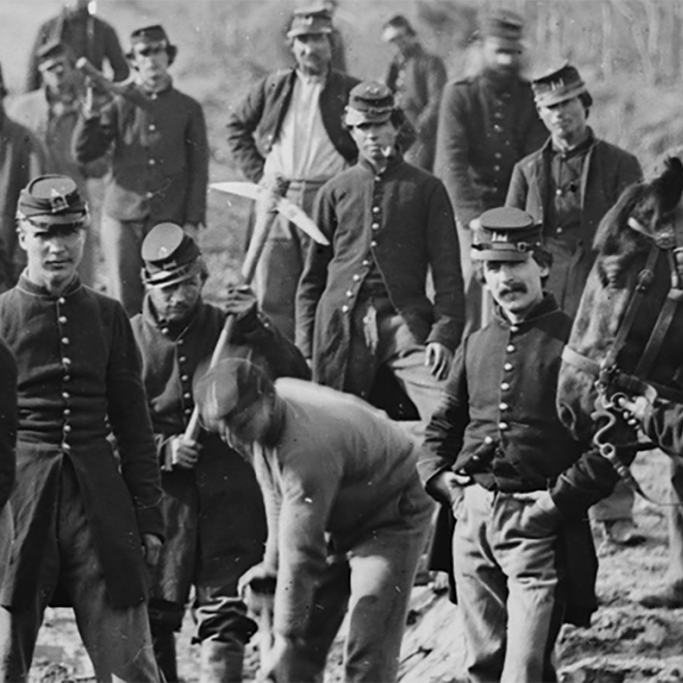

Patrick answered the call and enlisted in the 15th Regiment, NY Infantry for a 2 year term of service in a sappers and miners unit. Sappers are combat engineers tasked with every kind of construction or destruction required to move troops around or defend them in position. His company, Company D, was recruited from New York City, Brooklyn, and New Jersey. Patrick enlisted in New York – Brooklyn was not yet a borough of the city.

23 MAY 1861 – Fort Schuyler

The 15th initially gathered at Fort Schuyler in the Bronx. It was dedicated in 1856 and designed to protect New York City from a naval attack through the Long Island Sound. It housed a military hospital with a 2000 bed capacity and would eventually serve as a POW camp. Patrick’s regiment was outfitted and began their military training there.

3 JUN 1861 – Willet’s Point

Willet’s Point was purchased by the US government in 1857 to defend the naval approach to New York City – in tandem with Fort Schuyler, directly across on the East River. But there was still no fort in place on JUN 3, 1861 when Patrick’s regiment was ordered there. Their initial task was to help construct what became Camp Morgan. It would be more than a year before construction of a Fort would begin in earnest – ironically, from a design by Robert E. Lee.

The 15th Regiment was still a state militia at that time, and it had to be mustered into national service. Companies A, B, E, F, G, H, I, and K were mustered in on JUN 17, 1861, and Companies C and D on JUN 25, 1861 – but records are often misdated JUN 17, 1861.

Patrick served under Captain Julius C. Hicks, a native of Rutland VT and a builder by trade. It was Hicks who later signed his discharge paperwork. The captain’s brother Charles – a testament to the complexities of civil war – was a confederate officer and a spy.

29 JUN 1861 – Washington DC

Patrick went to war with the 15th regiment on JUN 29, 1861. They traveled by steamship from Willet’s Point, across the Arthur Kill to ElizabethPort, NJ. From there, they continued by train on the Washington Branch of the Baltimore & Ohio Line – transiting Trenton, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Annapolis Junction. They arrived in Washington between 6:30 and 7pm on JUN 30, 1861.

They were there to defend the capital and they spent a month encamped on Pennsylvania Ave.

21 JUL 1861 – Episcopal Theological Seminary

In high summer, they were deployed to the peninsula, and traveled by steamship to Alexandria where they were assigned to McCunn’s Brigade. They were encamped at the Episcopal Theological Seminary where they were transferred to Franklin’s Brigade on AUG 4 and Newton’s Brigade on SEP 26.

For most of the summer and into the fall they were on picket duty in and around Fall’s Church, Bailey’s Crossroads, the Seminary, and Cloud’s Mills – all suburbs of Alexandria. A picket – if you’re wondering – is a soldier, or small unit of soldiers, placed on a line forward of a position to provide warning of an enemy advance.

25 OCT 1861 – Training in Alexandria

Though the initial intention was for the 15th to be a sappers and miner’s unit, they had been working as regular infantry with the Army of the Potomac until the War Department reclassified them on OCT 25, 1861, and placed them in the Engineer Brigade under Lt. Col. Barton S. Alexander. In November, they were ordered to Alexandria to recieve engineering training and stayed until late MAR 1862.

22 MAR 1862 – The Peninsula Campaign

Major General George McClellen’s intended to quickly end the war by capturing Richmond – the capital of the Confederacy. He sailed with the Army of the Potomac, including the Engineer Brigade, to Fort Monroe in Hampton, VA on MAR 22, 1861 to begin the Peninsula Campaign. First step, take Yorktown.

5 APR – 4 MAY 1962 – The Siege of Yorktown

The 15th Regiment marched from Fort Monroe to Yorktown with the Army of the Potomac – a distance of 25 miles – and on arrival immediately began building siege materials.

By the time Confederate forces evacuated a month later, the Engineer Brigade had constructed over 5000 yards of roads, 3 ponton bridges, 2 log crib-work bridges, and 1 floating raft bridge over the Black & Wormsley creeks. They built innumerable gabions and fascines, and Battery #4 on Moore’s Plateau.

MAY 1862 – Advance up the Peninsula

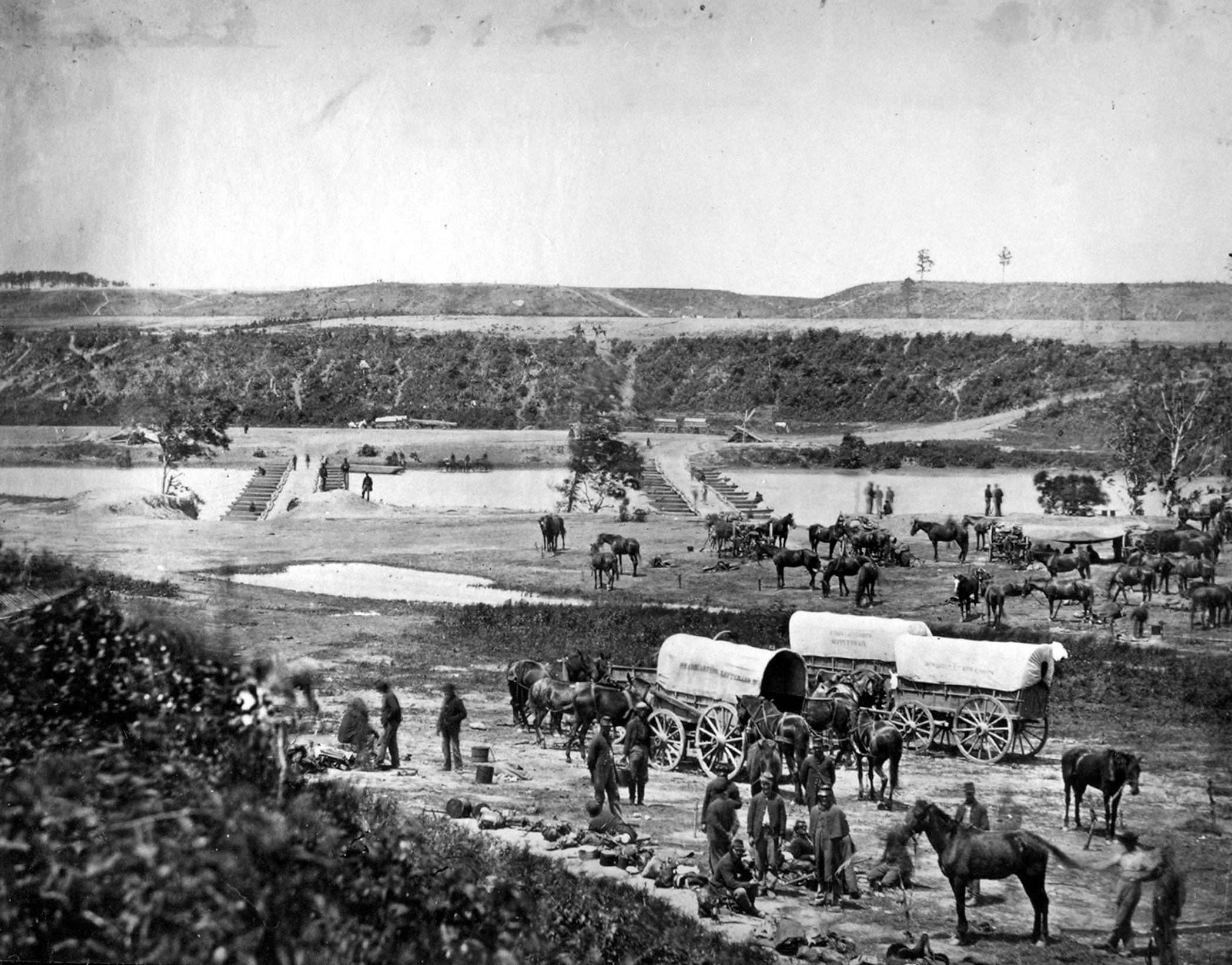

When Confederate forces evacuated, Franklin’s Division chose to land further inland at West Point, instead of at Gloucester Point across from Yorktown. The 15th Engineers were sent to assist in the landing.

They tied canal barges together and covered them with decking, then used these makeshift rafts to ferry heavy artillery to shore. At the shore, the rafts were tied to a planked bridge allowing the artillery to be wheeled off the ship and up the beach without ever being mired down in sand. The rafts were then tied together and grounded at the shore to create a wharf reaching 220 feet into the river, which could then be used to unload cargo. They moved 8000 men and all their equipment from ship to shore in just 3 hours.

Between MAY 16 and JUN 27, the Engineering Brigade built 12 bridges over the Chickahominy river to facilitate the Army’s advance up the peninsula. The goal was to take Richmond.

25 JUN – JUL 1 1862 – The Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles are a series of 6 major battles fought over 7 days east of Richmond which ended with the Union army in retreat.

Robert E. Lee saw the large and well supplied Union army advancing up the Chickahominy towards Richmond and this forced him to rethink his tactics. Instead of a defensive posture, he adopted an aggressive, offensive posture which immediately halted McClellen’s advance and then reversed it.

The 15th Engineers were at Seven Pines, White Oak Swamp and Charles City Cross Roads, mostly building or rebuilding bridges and keeping roads open for retreating Union forces. But when McClellen had the advantage of higher ground, he made a stand at Malvern Hill and there he used the 15th Regiment as regular infantry.

Lee ordered thousands of Confederates to storm Malvern Hill, against a seemingly hopeless barrage of artillery fire. One Confederate officer later said, “It was not war, but murder.” Lee was willing to “spend” the men in a way that was unnerving to McClellen, and it won him the day.

The casualties and loses were extreme. All in, it cost the Confederacy 20,000 men or 22% of their engaged forces. The Union lost just under 19,000 men, just over 16% of their engaged forces. There is a notation in the Union Engineer Battalion records that this retreat was the most disappointing march of the entire war.

1 JUL – 16 AUG 1862 – Harrison’s Landing

Patrick and the 15th engineers retreated to regroup at Harrison’s Landing with the Army of the Potomac.

Abraham Lincoln traveled there to meet McClellen and inspect the troops on JUL 8, 1862. Demoralized from the defeat, with his army huddled on the north bank of the James River and defended by Navy gunboats, McClellen handed Lincoln an unsolicited letter suggesting that the goal should be a reunion with the southern states, leaving slavery intact. Lincoln, on the other hand, believed the savagery of the Seven Days Battle was a license to expand the scope of the war to include emancipation.

We can’t know if Patrick Hassett saw President Lincoln at Harrison’s Landing – they were certainly there at the same time – but we can be sure he was present for the first playing of ‘Taps’. In July, while at Harrison’s Landing, Brigadier General Daniel Butterfield rearranged an old tune – once called the ‘Scott Tattoo’ – and began using it to signal light’s out instead of the French bugle call they had been using. Butterfield’s bugler, Oliver Wilcox Norton was the first to sound the new call and within months “Taps” was used by both Union and Confederate forces. It was officially recognized by the United States Army in 1874. (SRC)

10 AUG – 1 SEP 1862 – End of the Peninsula Campaign

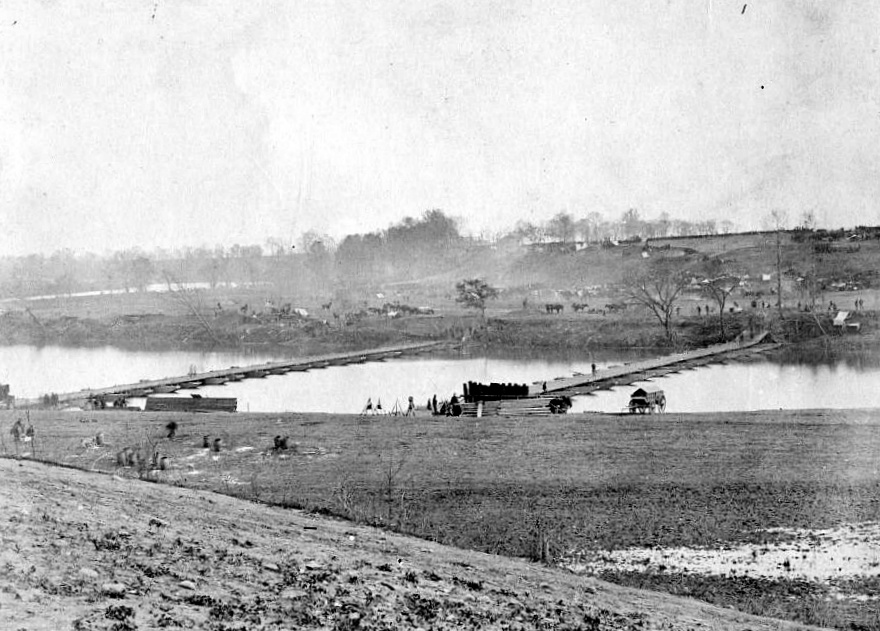

On AUG 10, the Engineer Brigade was ordered to build a bridge near the mouth of the Chickahominy. Company D went overland to Barrett’s Ferry – the intended site – but the materials had to be sent from 60 miles away at Fort Monroe and they arrived at dawn on AUG 13. Work began immediately and by 9:30am the next morning, the bridge was completed – 1,980 feet long, with 5 spans of trestles and 96 boats. The entire Army of the Potomac, it’s gear and artillery, crossed over by 10 am. By 3pm, the bridge was dismantled and the materials were on a steamer returning to Fort Monroe.

The Army of the Potomac, the 15th Engineers, and Patrick Hassett were back safe in Alexandria, VA by SEP 1, 1862. The Peninsula campaign had ended.

4-27 SEP 1862 – The Antietam Campaign

Robert E. Lee knew that the north could outman and outgun the south. So he pinned his hopes for southern independence on the morale of the northern people. If they were demoralized, if the cost was too high, if he could make keeping the south more trouble than it was worth, the Confederacy would stand – and he wanted the northern people to reach that conclusion before the November elections.

Lincoln had called for 300,000 new volunteers, there was a crisis of confidence in military leadership, and Union forces were trying to regroup at Washington. At that moment, with the north still reeling from the loss of the Peninsula Campaign, Lee decided to press his advantage by invading Maryland. Confederates began pouring over the border on SEP 4, 1862.

McClellen intercepted Lee’s orders, so he knew that Lee’s forces would be split with Stonewall Jackson attacking the garrison at Harper’s Ferry, and Lee continuing north into Maryland. By SEP 7, the Engineer Brigade was on the march to Antietam with McClellen’s forces – facilitating the transport of over 100,000 men through passes in the South Mountains and building 2 fords across Antietam Creek. McClellen’s advance was delayed by the Battle of South Mountain on SEP 14, but he met Lee’s consolidated forces at Sharpsburg on SEP 17. It was the single bloodiest day in American military history – 22,000 casualties.

On SEP 18, outnumbered 2 to 1, Lee pulled back across the Potomac. There were some additional skirmishes by Lee’s rear guard in retreat, and McClellen could have pursued the Confederates to press his advantage – but chose not to. By SEP 20, both the Maryland Campaign and McClellen’s military career were at an end. He was replaced by Ambrose Burnside as head of the Army of the Potomac.

On SEP 19, the Engineer Brigade was deployed to Harper’s Ferry which had fallen to Stonewall Jackson. They were to clear a path for the returning Army of the Potomac after Antietam. From the SEP 21-25, they re-raised a ponton bridge across the Potomac that had been burned after the surrender of Harper’s Ferry and on the SEP 27th they laid another bridge across the Shenandoah River. They left the Harper’s Ferry area on NOV 3 for Warrenton, VA.

Lincoln wanted Burnside to be aggressive and, like McClellen, Burnside proposed to take Richmond. He would cross the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg and race to the Confederate capital before Lee’s troops could stop him. When Lincoln approved this plan in mid-NOV, the Engineers were moved to Falmouth – across the river from Fredericksburg – to start building bridges.

But the first of the pontons needed for bridge construction arrived a week after Burnside’s forces. They had been ordered on NOV 7 and were to be sent overland and by river to Falmouth. On NOV 14, the pontons were ready to go, but the 270 horses needed to move them were missing. When Burnside arrived at Falmouth, most of the pontons were still on the Potomac. On NOV 25, there were enough pontons for a single bridge, and though their crossing would be opposed, only half of Lee’s forces were at Fredericksburg and not yet dug in. Burnside chose to wait for the remaining materials – and it would cost him. That delay allowed Lee to reunite his forces and entrench at Fredericksburg.

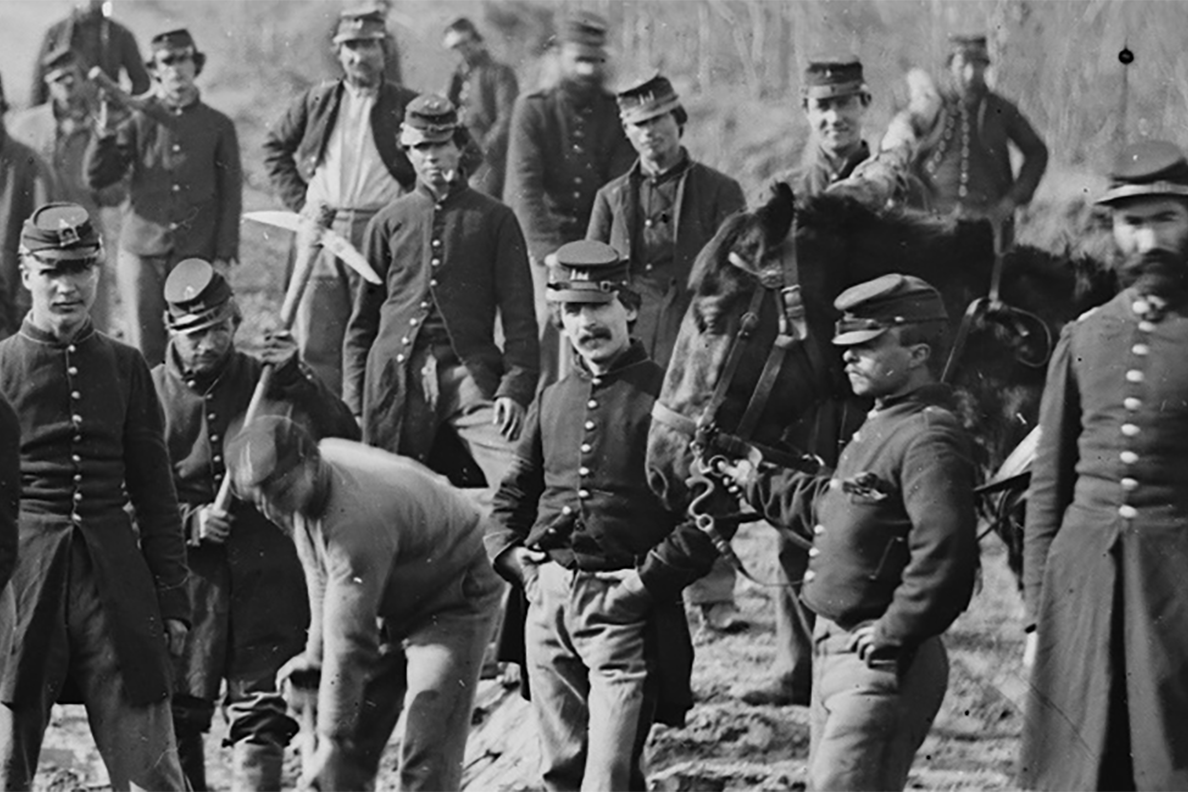

The remaining pontons arrived at 3am on DEC 11 and 6 bridges were to be completed by dawn. The 15th Engineers completed their bridge at the lower end of town by 9am, in spite of incessant sniper fire, and then turned to help the 50th and the battalion complete theirs as well. But construction was slowed all along the river by Confederate sharpshooters so Burnside order the bombing of Fredericksburg. He leveled it. He then sent troops across the river in ponton boats to route the sharpshooters and provide cover for the unarmed engineers.

What followed is an object lesson in urban combat. Despite repeated frontal assaults and superior numbers, Burnside failed to take Fredericksburg and withdrew his army on DEC 15, 1862. The Engineer Brigade stayed to dismantled the bridges on DEC 16. Lee suffered 4201 casualties – about 5% of his men. Burnside, now known as the “Butcher of Fredericksburg” suffered 12,653 casualties – almost 10% of his men. Miraculously, there were only about 4 civilian casualties.

17 DEC 1862 – APR 26 1863 – The Mud March

Humiliated by his loss at Fredericksburg, Burnside immediately began plotting another crossing further down the Rappahannock. Two of his generals had so completely lost faith in him, they took leave, traveled to DC, met with Lincoln and told him that the Army of the Potomac was in such a terrible state that any new campaign would likely tear it apart. Lincoln telegrammed Burnside that no troop movements should be made without approval. Burnside changed his plans only slightly and tried to cross further up river at Banks’ Ford.

The engineers were suppose to build 5 bridges at dawn on JAN 21, but overnight it began to rain. The weather had been unseasonably warm and the ground wasn’t frozen. The banks turned to mud. As the first bridge was nearing completion, the rain continued, and Burnside began moving his artillery, caissons and wagons towards the bridge. They mired down in mud. By the 22nd, Lee’s forces were assembling across the river – it was still raining – and sharp shooters began sniping at Burnside’s troops. Rather than face another defeat, Burnside gave the order for the army to retire.

After the ‘Mud March’, morale was at an all time low and desertions at an all time high. Burnside was replaced by Major General Joseph Hooker on JAN 26, 1863 who proved to be an effective administrator. He used the winter of 1862-63 to reorganize the military bureaucracy in a way that improved diet and sanitary conditions for the men – it made him popular. Hooker’s army, the 15th included, wintered over at Falmouth, directly across the river from Lee’s army not far from Fredericksburg.

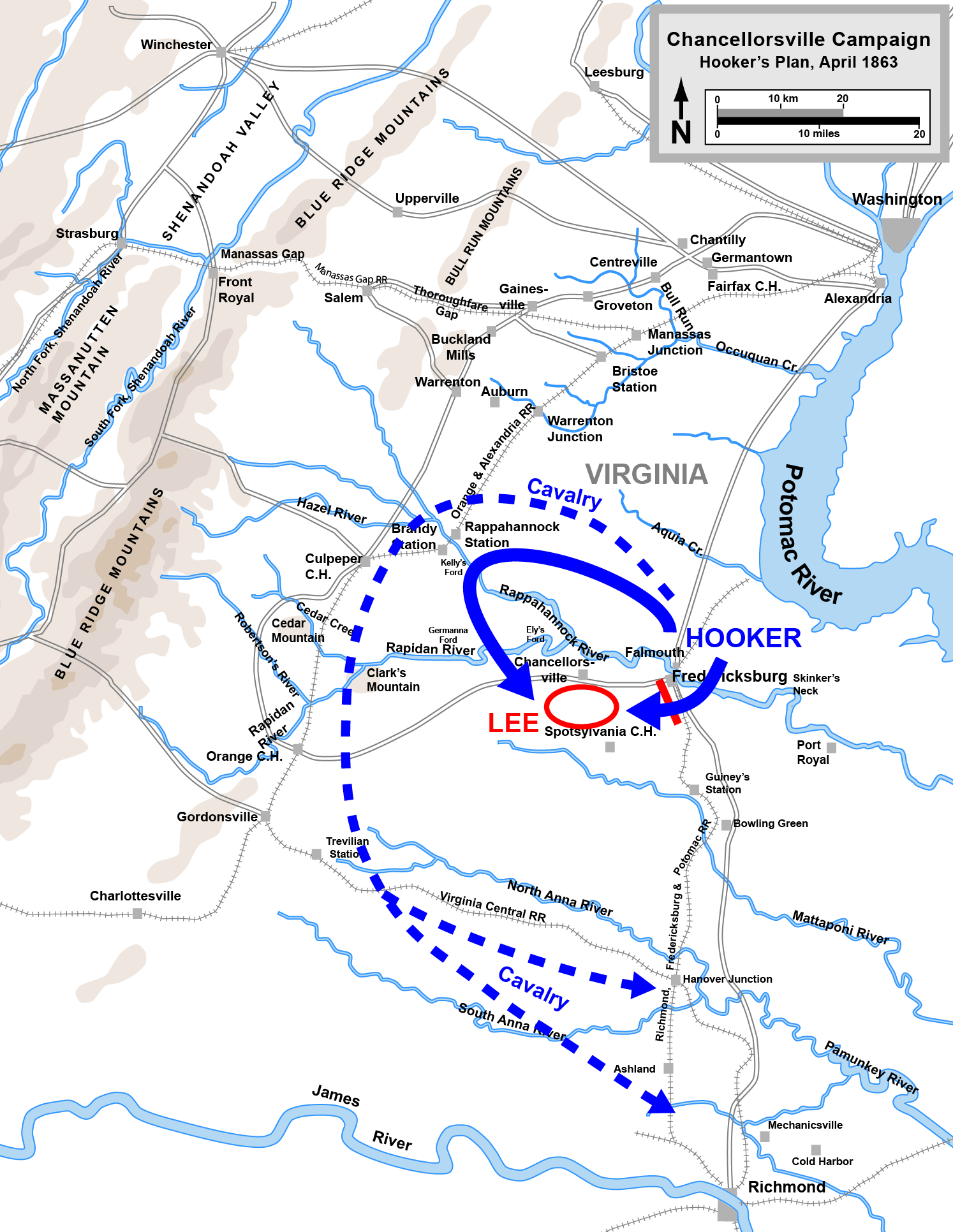

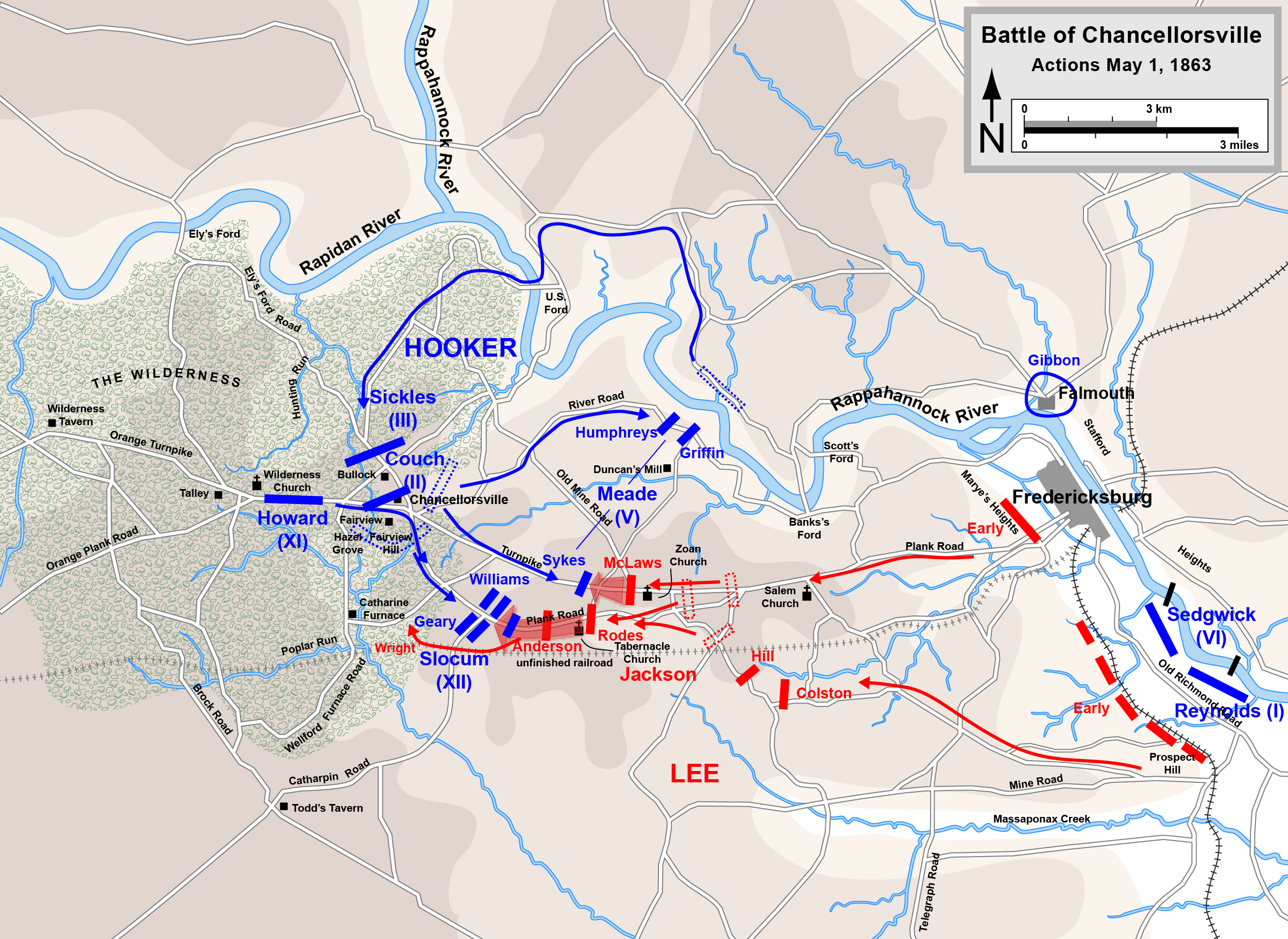

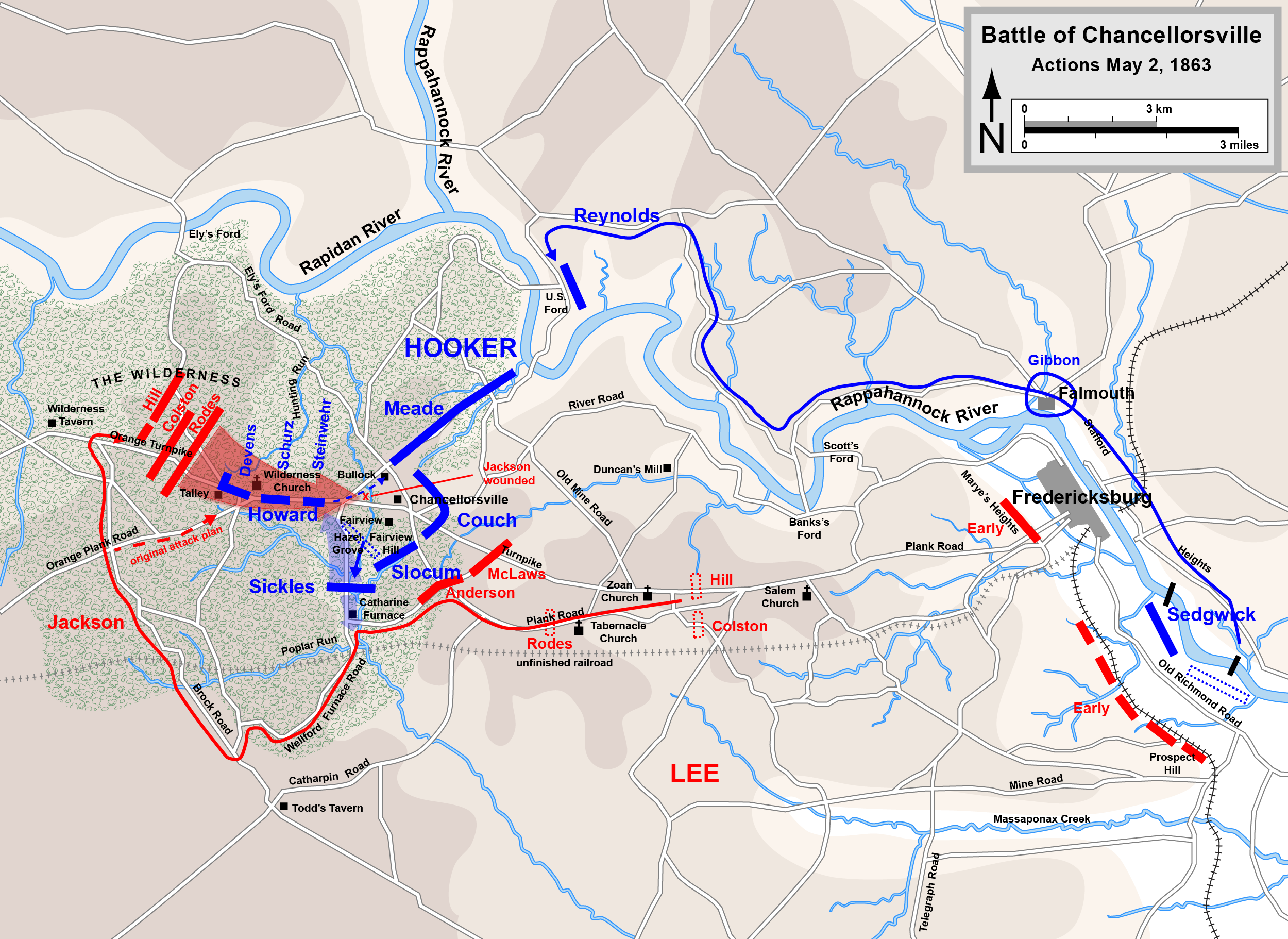

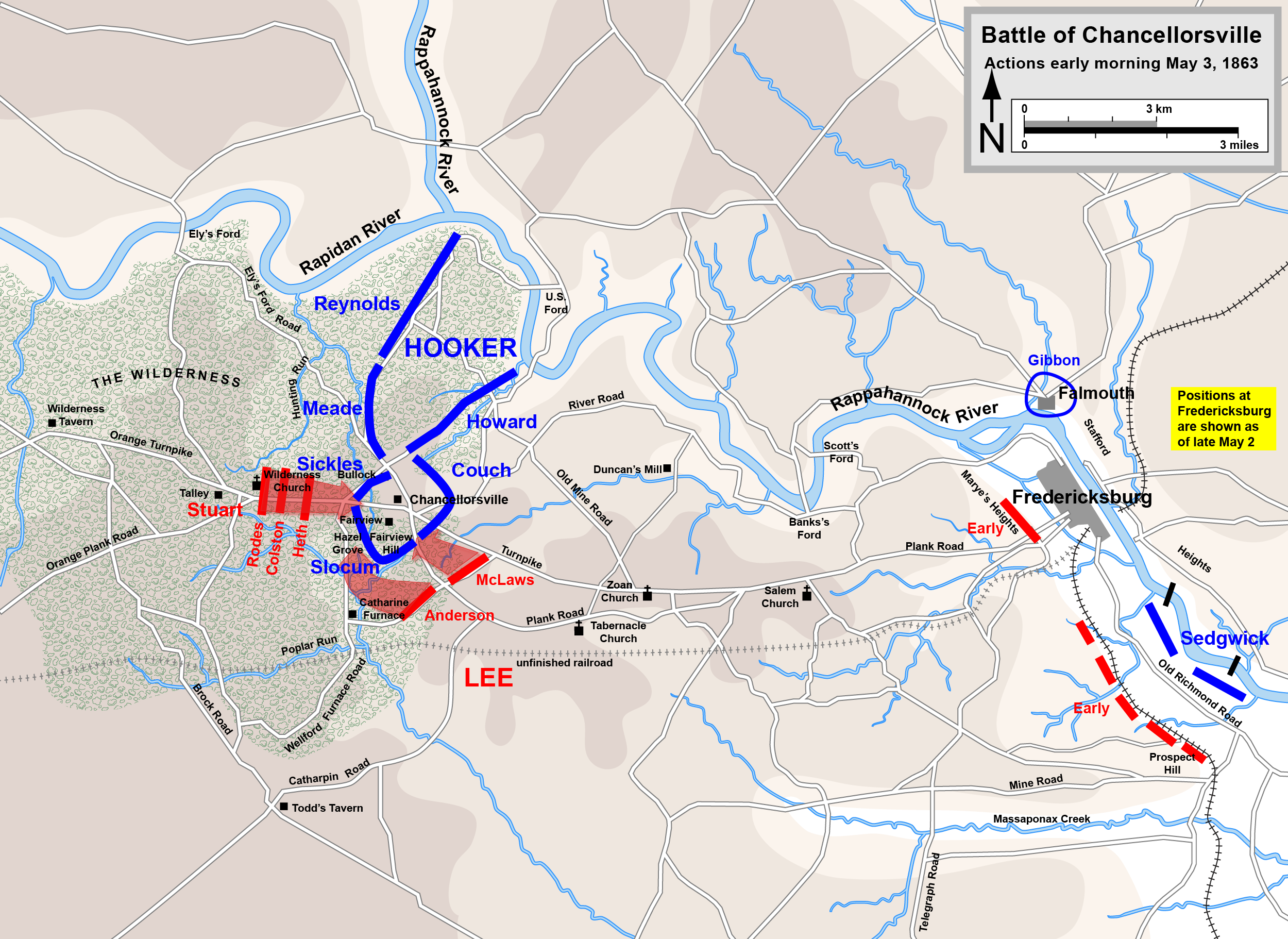

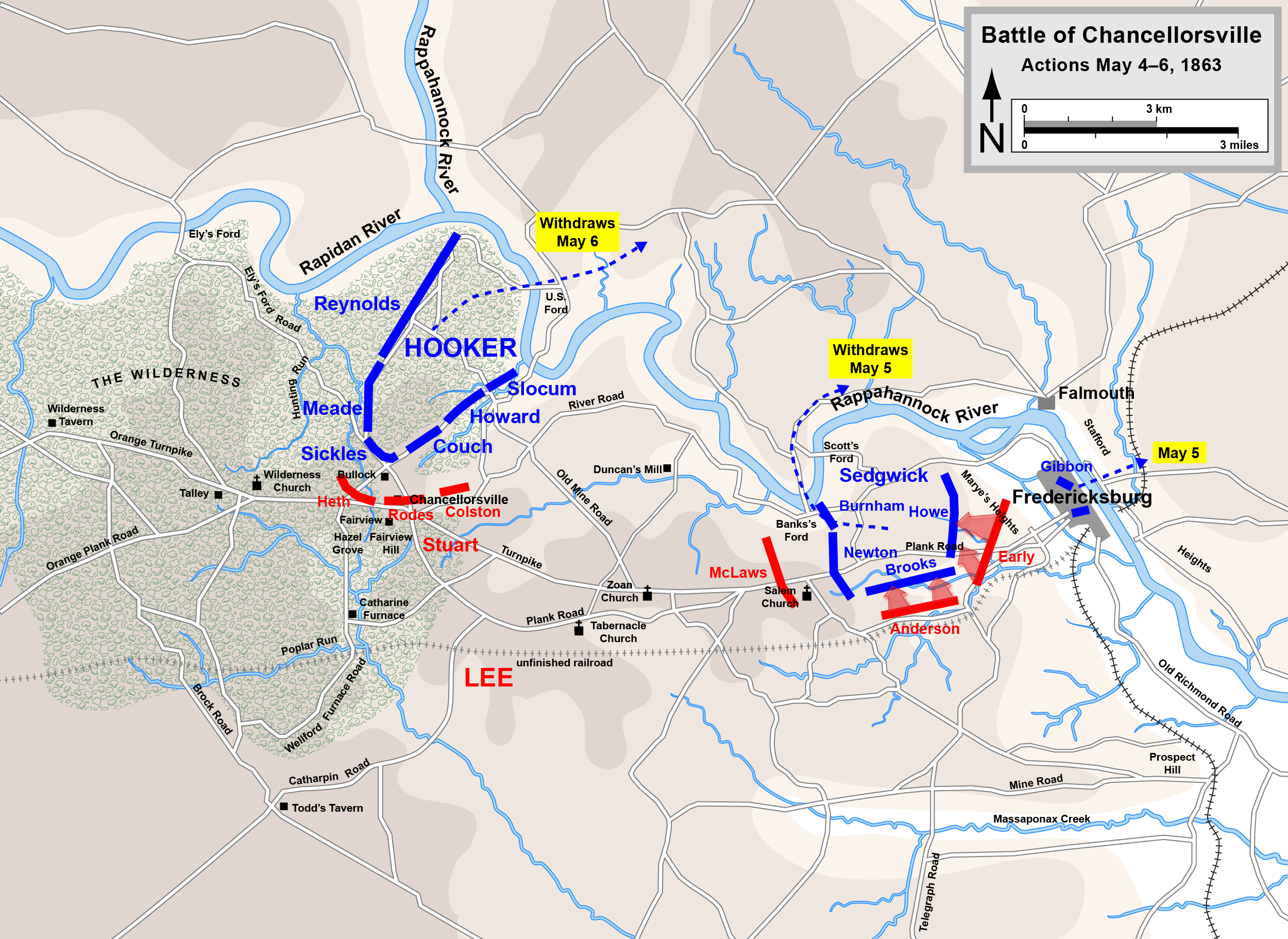

APR 27 – MAY 6, 1863 – The Chancellorsville Campaign

Hooker’s army was in good shape that spring and he intended to attack Lee on multiple fronts. He would send troops to circle behind Lee, attacking Confederate supply lines, and cross his troops at 2 points on the river to flank the Confederate army on 2 sides. In the face of a much larger, better supplied army, Lee chose – surprisingly – to divide his forces and ended by outflanking Hooker instead. The Army of the Potomac was once again driven back across the Rappahannock. It’s considered Lee’s greatest victory.

The Chancellorsville campaign consisted of 3 battles and a cavalry charge – all of which occurred over a small area of Spotsylvania. The Engineer Brigade, including the 15th Regiment, constructed and dismantled 16 bridges across the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers as part of this campaign.

Hooker suffered 17,287 casualties – about 13% of his forces. Lee suffered 13,303 casualties – about 22% of his forces, including the loss of Stonewall Jackson who died of friendly fire.

The Plan vs The Battle (Wikipedia)

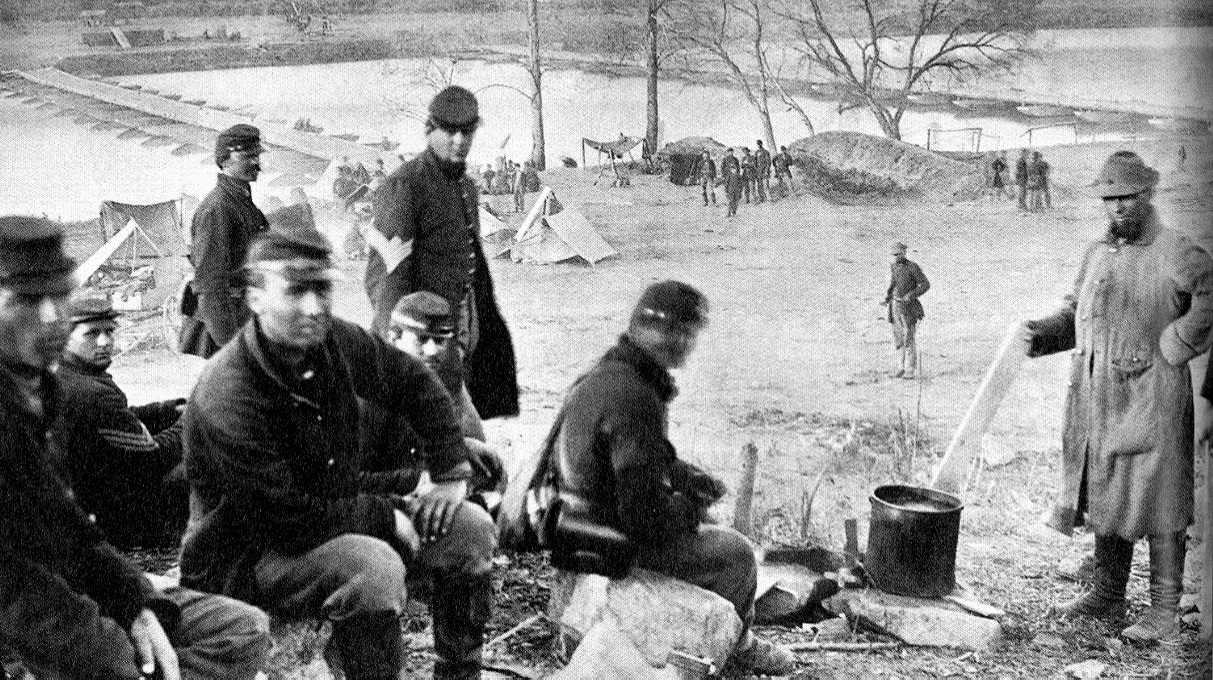

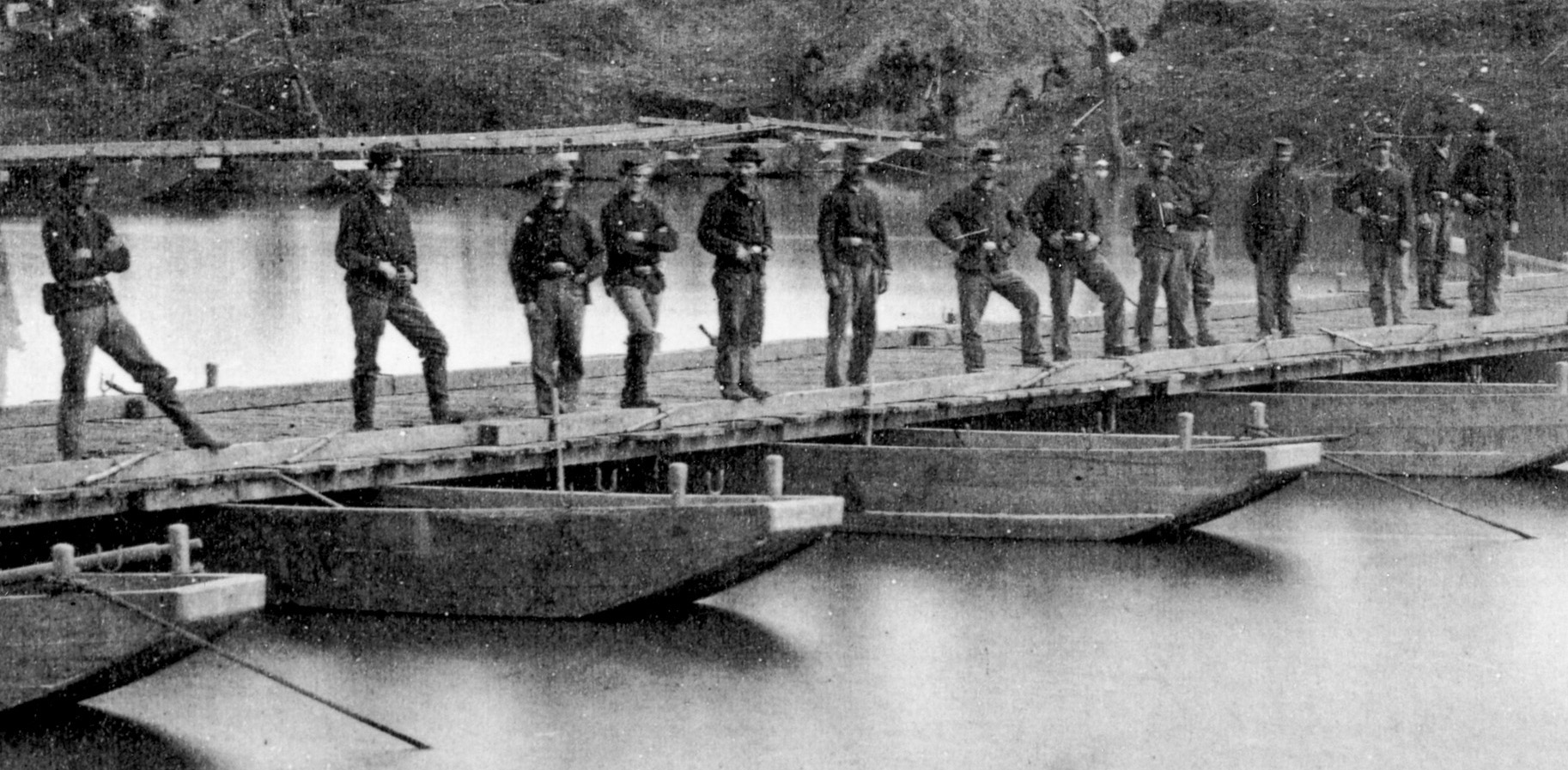

5-13 JUN, 1863 – Battle of Franklin’s Crossing

The Battle of Franklin’s Crossing took place near Fredericksburg and was basically a reconnaissance mission turned skirmish. Union troops crossed the Rappahannock to determine the position of Lee’s army and were pushed back by Confederate forces. The Engineer Brigade did service in this battle – probably the bridge you see below. This very small conflict is generally regarded as the first action in the Gettysburg campaign but it was also the last action in Patrick Hassett’s war.

25 JUN 1863 – Mustering Out

Patrick was a private, once promoted to private 1st Class, but at some point busted down again. He spent the war as a rank and file sapper, and for him the war was over. Those who volunteered or were drafted after JAN 1862 had 3 years terms of service, but Patrick and other early volunteers were only committed to 2 years and the 2-year men of the 15th Regiment were returned to New York on JUN 18. They mustered out on JUN 25, 1863 – just a week before the battle of Gettysburg, where 50,000 men died in 3 days.

There is a monument to the 15th & 50th NY Engineers on the battlefield at Gettysburg. Over the course of the war, the 15th Regiment had 4 men lost or killed in action, 1 dead from wounds recieved in action, and another 129 dead from disease.

More than a year after Patrick enlisted, Congress saw fit to reward the sacrifice of its immigrant soldiers.

“Any alien, of the age of twenty-one years and upwards, who has enlisted, or may enlist in the armies of the United States, either the regulars or volunteer forces, and has been, or may be hereafter, honorably discharged, shall be admitted to become a citizen of the United States, upon his petition, without any previous declaration of intention to become such; and he shall not be required to prove more than one year’s residence.” (Act of July 17, 1862, 12 Stat. 597, section 21)

Patrick was now an American.

Marriage

We don’t know how Patrick met his wife, Catherine McAllen, but it was probably through work. Patrick was a hatter and Catherine, a hat trimmer. She was born in Westminster, London – to Irish parents – who emigrated with her to Orange, NJ by 1850.

Orange was a huge center of hat making with over 30 manufacturers in and around the city. Brooklyn was likewise full of factories – most notably Knox Hat Works. It may be that Catherine moved to Brooklyn for work, or that Patrick visited Orange for a related reason – but somehow they met and married in Brooklyn on JUN 2, 1869.

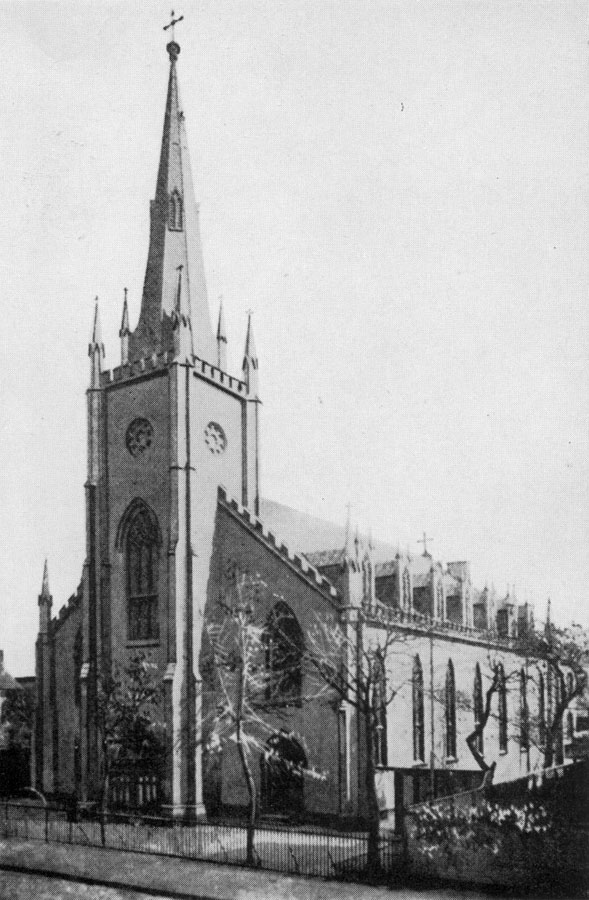

It was a first marriage for both them. He was 29 and she 24. They were living in Brooklyn at the time and their civil marriage record was signed by a Catholic priest named John Fagan who was living at 42 3rd Street in Williamsburg. Quick work with a map and a diocese directory shows that Father Fagan was with The Church of St. Peter and St. Paul – an immigrant church and the first ecclesiastical design by Patrick Keeley. It was dedicated in 1848 but nearly burned to the ground by anti-immigrant Know-Nothings in the 1850’s. The Mayor of Brooklyn saved it.

There were lots of Hassetts in the congregation – Maria, Margaret, Michael, Hannah, Catherine, Lizzie, Timothy, Ann, James, Bridget, Ellen – and the witnesses at Patrick & Catherine’s wedding were William and Mary Flannery, née Hassett. William Flannery was a hatter and mentioned in the papers as a member of the Finisher’s/Maker’s Association. I’d hazard a guess that Mary was Patrick’s sister.

So the chances are when Patrick came to America, he had some family in Brooklyn and he may have had some help getting started as a hatter. But the young family wouldn’t stay in Brooklyn long, their first child, Josephine, was born 3 months later on SEP 12, 1869 in Orange, NJ.

Home & Family

In 1900 and 1910, Catherine told census takers that she and Patrick had 6 children – 3 surviving. But, in fact, there were 8 children – 3 surviving – and all born in Orange, NJ.

- Josephine, their eldest, was born SEP 12, 1869. She died in 1878, at the age of 9.

- John, their eldest son, was born around 1870. He survived well into old age, working as a grocery store manager and janitor. He married a woman named Anna Finneran and had at least 5 children: John, Bernard, James, Thomas and William.

- Thomas F. was born Nov 17, 1871 and died at the age of 4, on Feb 3, 1876.

- Mary E. went by her middle name – Emma – and was born OCT 14, 1873. She died at the age of 25, on MAY 2, 1898.

- James was born SEP 19 1875 and was a hatter, like his father. He died at the age of 20, on Mar 11, 1896.

- Adelaide Beatrice, my great-grandmother, was born FEB 27, 1878 and baptized at St. John’s Catholic Church in Orange, NJ. She worked, like her mother, as a milliner, and married Theodore Clarence Brintzinghoffer, a protestant, on JUN 1, 1910 in the rectory at Our Lady of the Valley. They had 2 children – James Henry and Catherine – and she lived to be 87 years old, passing away on JUN 3, 1965.

Genevieve was born on FEB 16, 1880 and, like her sister, was baptized at St. John’s. She never married but had a long career with Hahne’s Department store and later worked at a clothes pin factory. She passed away JUN 18, 1957.

Mary, the youngest, was born in 1881, but died by the age of 2 on MAR 5, 1883.

Patrick settled with his family at 10 Burnside St. in Orange, at least as early as 1880. Maybe it was close to the hat shop where he worked. When he died at Burnside just 6 years later, the family stayed on. Catherine was able to draw a pension from his military service and her widowed father came to live with them until about 1891.

She lived at 78 Tompkins for a time and, in 1893, at 63 Nassau. In 1904, she moved to 69 Chestnut and stayed there, more or less, until 1925 – with a brief stay at 41 Mitchell around 1916.

She continued to live with her children until the end of her life, and was still living with Genevieve in 1930 at 543 Lincoln Ave. Orange, NJ. She passed away in August of 1931 and is buried at St. John’s with her parents and her husband Patrick.

Taps

Patrick died a young man, just 55. He developed pleuropneumonia – essentially pneumonia complicated by an inflammation in the lining of the chest cavity. Having survived the Great Famine, having survived a war where 650,000 men died – two-thirds of them from disease – having survived 3 of his own children, he was felled by a viral infection.

He was ill for just 6 days when passed away on APR 27, 1886. He was buried at St. John’s Catholic Cemetery.