I wear a wedding ring that was previously worn by my grandmother, Elizabeth Irene Wiggans, but she was not the first to wear it. It’s inscription reads ‘TCB to KF May 27, 1874’ and it was originally made for my 2nd great-grandmother, Catherine (‘Kate’) Forman. It took six years to piece together Catherine’s story and this history will focus on just the line of her Forman ancestors.

The Forman surname comes from an Old English word for ‘farm manager’. It pre-dates the Viking invasion and goes back unchanged for at least 700 years in Lincolnshire. The earliest surviving reference is a land grant for Ralph Forman dating to 1316.

The first ‘Forman’ in America is an Englishman named Robert Engle Forman who arrived with his wife, Johanna Pore, in 1645. Robert and the 12 generations that follow him are well documented and undisputed – but the 4 preceding English generations are a bit in question. For centuries, it’s been contended that Robert Engle Forman was descended from an illegitimate son of Sir William Forman of Lincolnshire. The trouble is – I can’t prove it.

So if you’re curious to explore the contents of a 300 year old rumor and the life of Sir William, read on. But if you’d prefer ‘just the facts’, skip ahead to Robert Engle Forman.

James Brintzinghoffer ← Theodore C. Brintzinghoffer ← Catherine Forman ← William Spencer Forman ← Robert Forman ← William Forman ← Lewis Forman ← Aaron Forman ← Samuel Forman ← Aaron Forman ← Robert Engle Forman ←? William Forman ←? Robert Forman ←? William (illegitimate) ←? Sir William Forman. 1508-1546

Sir William Forman. 1508-1546

If rumors can be believed, my 15th great-grandfather is William Forman, a yeoman from Gainsborough in Lincolnshire, born at the end of 15th century. We know about him mostly through his son, Sir William Forman, who made a name for himself at the court of Henry VIII.

Sir William was a wealthy commoner, born in 1508 in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire. He was a haberdasher by trade and it seems likely that his trade took him London sometime in the 1510’s. He became an Alderman for the Cripplegate Ward of London in 1529 and served until his death in 1546. He was knighted by Henry VIII on October 18th, 1537 – just after his service as Sheriff of London in 1534, and just before his service as Lord Mayor in 1538.

If you’re wondering how a simple haberdasher could draw the attention of an anointed King – it all comes down to money. William and the tradesman of his age had money – Henry did not. He spent well beyond his means – borrowed heavily, taxed heavily and demanded that Parliament forgive all his debts. The Reformation in England and the Dissolution of the Monasteries that followed brought a fortune to the Crown but, even so, Elizabeth I inherited a debt not even Parliament could forgive. At the start of her reign the Crown owed £227,000 at 14% to the Antwerp Exchange – about £78,700,000 or $111,396,426 in today’s money.

Tradesmen, like William, made loans to the King and forgave his debts on an almost constant basis. It was the cost of doing business and for their trouble they were rewarded with various titles and positions. Sir William together with other tradesmen leased Tollsworth Manor from the Crown in 1544 and, a year later, made a loan of £900 against the security of 3 other estates in Surrey. It’s not clear any of them ever intended to live in Surrey.

Even Sir William’s brief stint in Parliament in 1545 was tied to Henry’s spending. His friend William Roche, a woolen exporter and member of Parliament, was sent to prison for balking at a new tax in front of the Council. Sir William was elected to replace him and as soon as Roche was released from prison, Sir William quickly stepped down, citing ill-health.

There is one description of Sir William that survives. As Lord Mayor, he mustered 15,000 troops for Henry and marched them in procession to Westminster where they were reviewed by the King. He made such a show if it, we still know what he wore.

They marched from Mile end to Whitehall, and from thence to Leadenhall, Sir Wm. Forman Knt., Lord Mayor was in bright harness, whereof the curass, the maynsers, gaunteletts and other parts were gilt upon the crests and bordures, and with that he had a coat of black velvet with a rich cross embroidered, and a great massy chain of gold about his neck, and on his head a cap of black velvet with a rich jewel, he had a goodly jennett richly trapped, with embroidery of gold set upon crimson velvet. About him attended 4 foot men all apparelled in white satin hose and all puffed over with white sarcenet.

8 MAY 1539. Records of the Corporation, Journal 14, folio 166

But here’s where the English Forman line goes a bit fuzzy. Sir William died on 13 JAN 1547 and was buried at the Church of St. George, Botolph Lane, in East Cheapside, London. At the time of his death, he was married to Dame Blanche Palmer, a thrice widowed heiress, and they had no surviving children. His only legitimate surviving heir, by an unknown wife, was a 9 year old girl named Elizabeth.

Additional sons are mentioned in several histories, but not in his will. So if they existed, they were not legitimate. The eldest of these rumored sons, William, became a merchant in London and then retired to Lincolnshire. He had a son, Robert, who had a son, William, who became a vicar in Buckinghamshire. This Reverend William Forman is said to be the father of Robert Engle Forman who arrived in America in 1645.

Robert Engle Forman. 1605-1671

Robert Engle Forman, my 10th great-grandfather, was born about 1605 in England and he was a Separatist. Neither Catholic nor Church of England, Separatists felt the Reformation should have gone further and they were quickly outlawed. In 1606, Archbishop Tobias Matthew was tasked by James I with driving Separatists and Catholics from the country – and he did a spectacular job of it.

Robert’s branch of Separatistism was based in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire – the same city where Sir William was born a century earlier. They worshipped for a time in Gainsborough Old Hall, but the congregation grew too large to continue meeting safely, so they split in two.

But after these things they could not long continue in any peaceable condition, but were hunted & persecuted on every side, so as their former afflictions were but as flea-bitings in comparison of these which now came upon them. For some were taken & clapt up in prison, others had their houses besett & watcht night and day, & hardly escaped their hands; and ye most were faine to flie & leave their howses & habitations, and the means of their livelehood.

William Bradford, Governor, Plymouth Bay Colony

The Scrooby Congregation, eventually migrated to Leiden where they more or less merged with the Puritans, and finally emigrated to found Plymouth Bay Colony. The remaining Gainsborough Separatists, under Reverend John Smyth, made their way to The Netherlands in 1607 or 1608, where they became Anabaptist. Robert was part of this later group.

He migrated to The Netherlands, mostly probably with his parents and most probably around 1608. We believe he landed in Vlissingen because a 19th century biographer claimed to have seen his name and the name of his wife, Johanna Pore, in a parish register there – but Vlissingen was fire-bombed in WWII, so there is no remaining record to prove it.

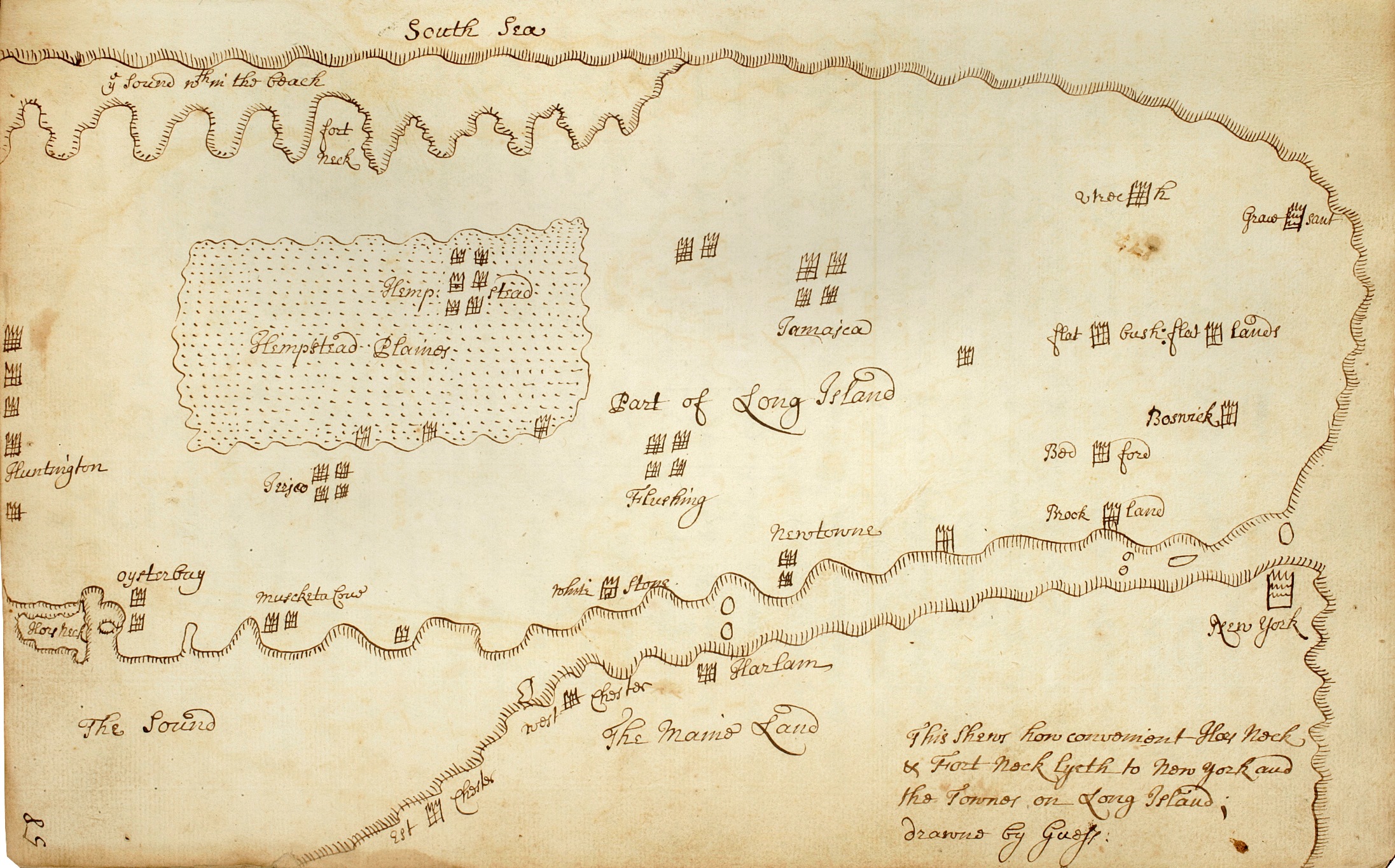

What we know for sure is that Robert Forman showed up in New Amsterdam – now New York City – with 17 other mostly English men on 10 OCT 1645 asking the Dutch Governor for a patent to form a settlement on Long Island.

Know all men, whom these presents may any wayes concerne, That wee William Kieft, Esquire Governor General of the Province called the New Netherlands, with ye Councill of State there Established, by Vertue of a Commission under the hand and Seale of the High and Mighty Lords, the Estates General of ye United Belgick Provinces, His Highnesse, Frederick Hendrick, Prince of Orange…

The Flushing Patent. 10 OCT 1645. Read more…

They wanted to call it Vlissingen – Vlissing for short – in honor of the Dutch town that gave them refuge. Their Anabaptist beliefs made them unwelcome in Plymouth Bay colony, but New Netherlands was more permissive in matters of religion. They would not be allowed to form congregations in Vlissing – you would know it as Flushing – but they would have ‘freedom of conscience’.

Their timing, however, was exceptionally bad.

The Dutch West India Company had been pressuring Governor Kieft to make the New Netherlands project profitable so, against the advice of his council and without the support of colonists, he tried to extract tribute from the Lenape. When they resisted, he launched an unprovoked attack to compel compliance but he only succeeded in unifying all the Algonquin tribes against him and kicking off a 2 year conflict called Kieft’s War (1643-1645).

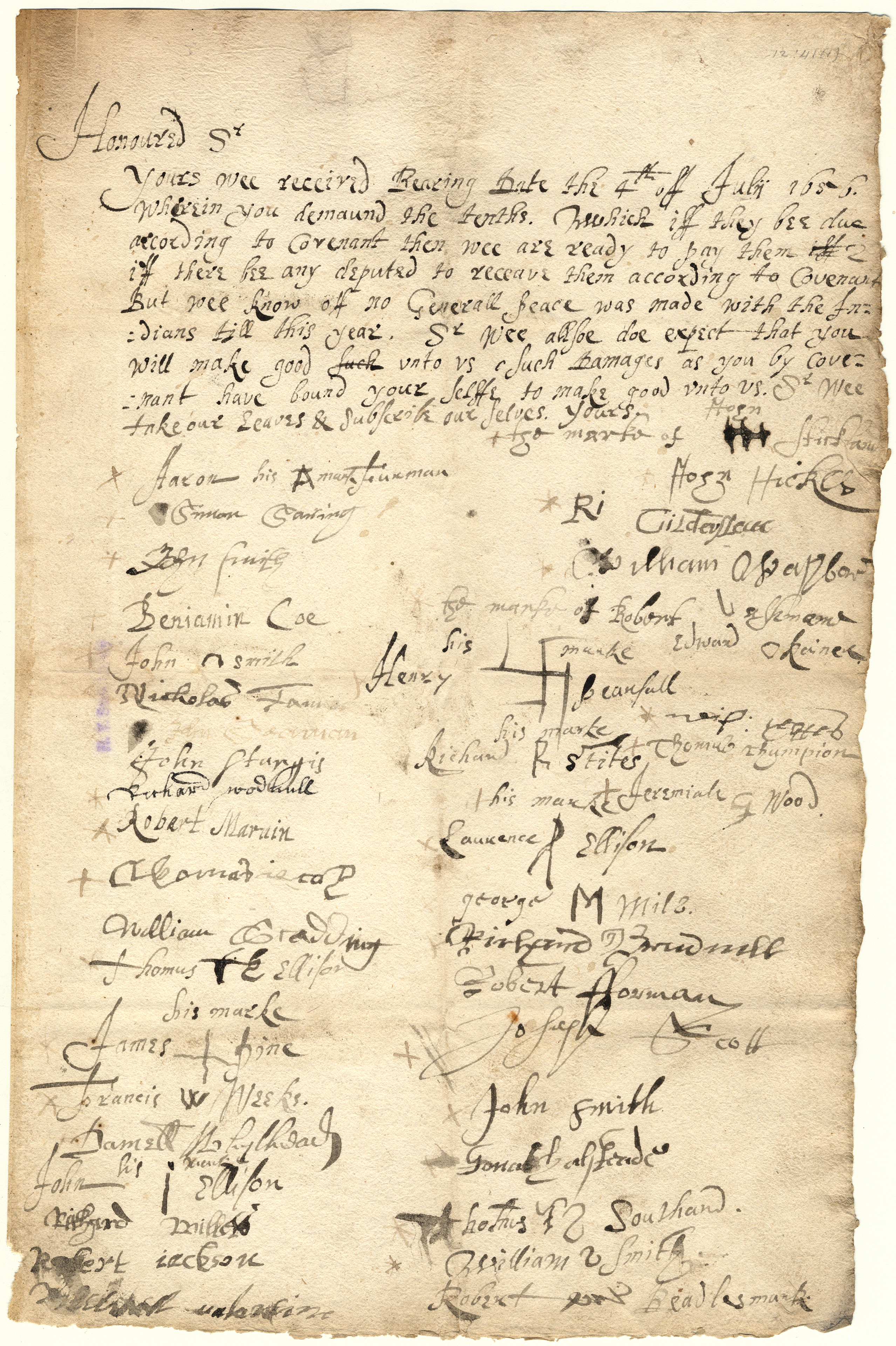

He was replaced by Pieter Stuyvesant in 1647 but the reprisals against colonists continued. Early Flushing records were destroyed in a fire – but we know that Robert didn’t stay long. By July 1656, he was living in Hempstead where he signed a letter that suggests the hostilities were ongoing. Responding to Governor Stuyvesant’s request for tithes, the settlers of Hempstead argued that none were due because New Netherlands had not met its obligation to provide peace, protection and compensation for damages.

Most of the Hempstead records related to Robert are heavy on references to grazing, acreage and cattle but the more interesting records begin in April, 1658 when Robert agreed to serve as an Assistant Magistrate in a trial against 2 Quaker women.

If you’re thinking that those who found religious freedom in the New World would be quick to offer it to others, you’d be wrong. New Netherlands offered ‘freedom of conscience’ to other Protestants, but it did not give them the right to form congregations and, in this period, it had no tolerance for Catholics, Jews or Quakers.

Foreasmuch as Mary Schott the wife of Joseph Schott together with the wife of Francis Weekes have contrary to the Law of God and the laws established in this place not only absented themselves from public worship of God but have profaned the Lord’s Day by going to a conventicle or meeting in the woods where there were two Quakers the one of them as named the wife of Francis Weekes being there and the other being met with all near the place who upon examination have justified their acts saying they did know no transgression they had done for they went to meet the people of God be it therefore ordered that each party shall paye for this offence twenty guilders and all costs and charges that shall arise therefrom.

Trial Of Mary Shott Under Robert Forman, Magistrate

Francis Weekes and Mary Schott were accused of congregating for the purpose of Quaker worship, found guilty and fined 20 guilders, plus costs. To make matters worse, Mary Schott was Robert’s next-door neighbor and tensions must have been high. Within weeks of the trial, Robert and Joseph Schott were ordered to erect a fence between their houses and threatened with fines if they didn’t have it completed within 10 days.

If that seems excessive, it wasn’t. In 1657, the year following this trial, Pieter Stuyvesant had a Quaker publicly tortured in New Amsterdam, and made it a crime to harbour a Quaker in your home. In Boston, a Quaker named Mary Dyer was hanged for the same offense.

In Flushing, some of the settlers – none of them Quaker – found the persecution of Quakers so offensive, they challenged Pieter Stuyvesant on his policies. It’s a beautiful document called the Flushing Remonstrance and it’s widely considered to be the basis of our constitutional right of religious freedom. It was signed by another one of my ancestors, Robert Field.

The law of love, peace and liberty in the states extending to Jews, Turks and Egyptians, as they are considered sonnes of Adam, which is the glory of the outward state of Holland, soe love, peace and liberty, extending to all in Christ Jesus, condemns hatred, war and bondage… our desire is not to offend one of his little ones, in whatsoever form, name or title hee appears in, whether Presbyterian, Independent, Baptist or Quaker, but shall be glad to see anything of God in any of them, desiring to doe unto all men as we desire all men should doe unto us, which is the true law both of Church and State… Therefore if any of these said persons come in love unto us, we cannot in conscience lay violent hands upon them, but give them free egresse and regresse unto our Town, and houses, as God shall persuade our consciences, for we are bounde by the law of God and man to doe good unto all men and evil to noe man.

Final paragraphs of the Flushing Remonstrance. 27 DEC 1657

Stuyvesant responded by jailing the authors and designating 13 MAR 1658 a ‘Day of Prayer’ for the purpose of repenting from the sin of religious tolerance. More to the point, he removed elected officials that he considered questionable and replaced them with more ‘reliable’ men. It may be that Robert’s willingness to serve on a Quaker trial made him seem like a ‘reliable’ man.

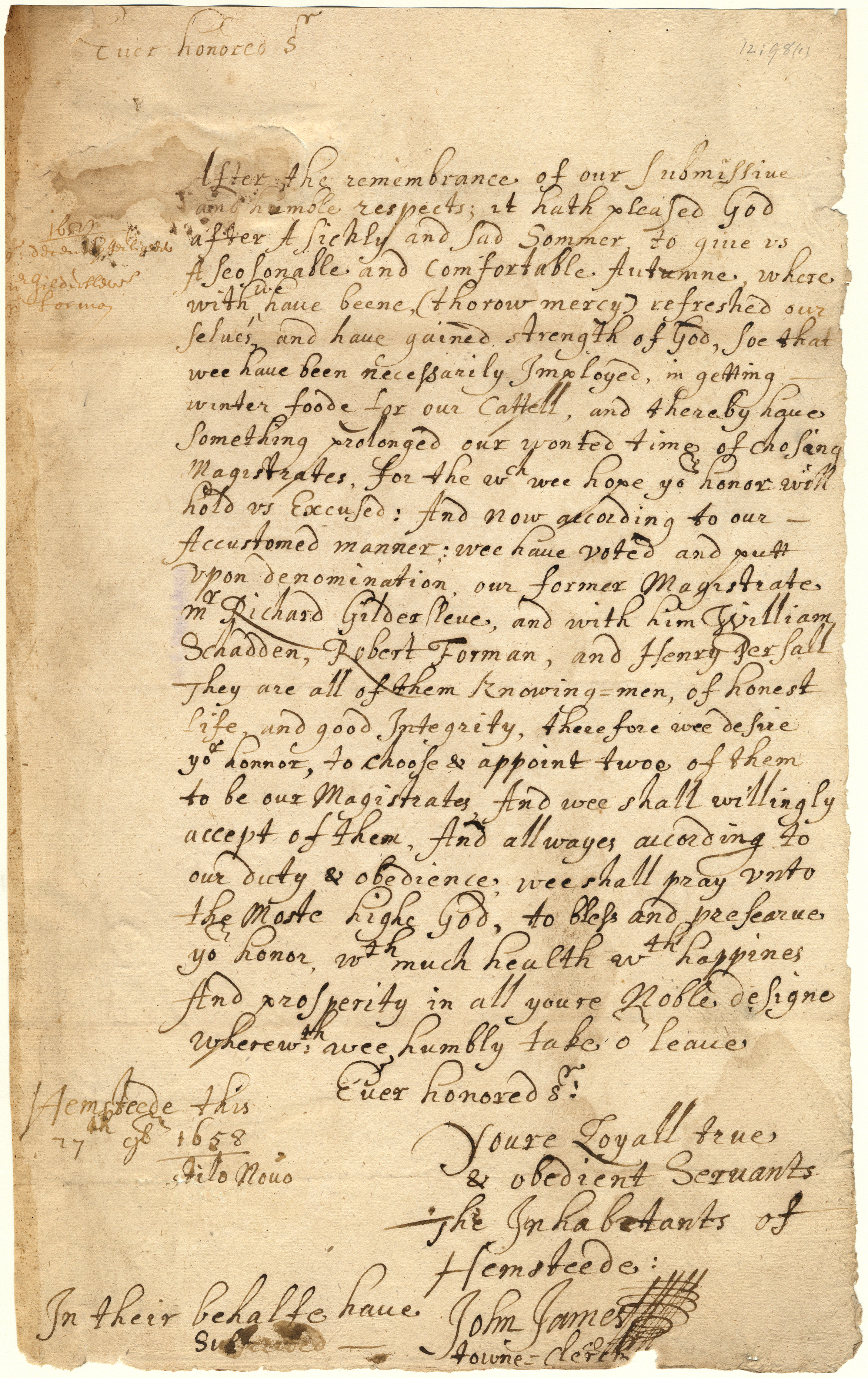

On 27 NOV 1658, Robert and 3 other men – ‘all of them knowing-men, of honest life and good integrity’ – were nominated to serve a one year term as Magistrate for 1659. Their names were sent to Pieter Stuyvesant for approval, and he selected Robert and Richard Gildersleve to serve.

But a year after his service as Hempstead Magistrate, Robert was living in Oyster Bay, Long Island. Oyster Bay was on the border of the Dutch and English colonies. The Dutch governed the area around Cold Spring Harbour, and land to the west. The English governed the area around Oyster Bay, and land to the east. Robert was living on the English side of the boundary in an area that had become a haven for Quakers fleeing the Dutch. The first record of Robert in that town is from the 1 FEB 1661, when he and his neighbors agreed to provide a widow with corn for the following year.

I found 16 records altogether – mostly related to property – but probably the most interesting is a deed for land bought from Robert Williams, a man he had known in Hempstead.

If ye said Robert fforman shall hapen to be disturbed, or Mollested Concerning ye befor Specefied fower Accers, of broaken up lands, or theare aboutes, which in ye term, of two yeares, after ye date heereof, Either by Indians, or any other person, or persons, whatsoever yt then ye said Robert Williams, is to geive in Lew thereof, fower Accers of his owne Manured hollowes.

Title insurance clause in a deed for land bought off of Robert Williams.

We have to assume Robert had troubles in his prior land dealings because in this particular transaction, he built in the old-fashioned equivalent of title insurance – he made Robert Williams agree to compensate him if he should be hassled by anyone for any reason over his right to the property within 2 years of the deal. And he must have been hassled because on 12 JUN 1662, Robert Williams had to swear before witnesses that he got the land from ‘Mohenas ye Indian ffreely’ and yet another record from 2 FEB 1668 shows Robert being compensated as the original deed prescribes.

We also know that he was made Magistrate again – this time in Oyster Bay, and this time by the English. His appointment, on 12 MAY 1664, came just 3 months before the English invasion of the Dutch colony. Three hundred English soldiers landed on Long Island on the 18 AUG 1664, seeking aid from English settlements en route to Brooklyn. In exchange for their surrender, The British allowed settlers to “peaceably enjoy whatsoever God’s blessing and their own honest industry have furnished them with and all other privileges with his majesty’s English subjects.”

When they reached New Amsterdam, Stuyvesant wanted to resist but he got no support from the merchants and settlers, who perhaps hoped the British would be better governors. The terms of surrender allowed the Dutch to keep their land, upheld religious freedom and kept the pubs open. (No, really – keeping the pubs open was listed 2nd on the terms of surrender- read it for yourself.)

Life went on as usual for the English on Long Island. As Robert’s life came to a close, his principle concern, as demonstrated in his will and the remaining town records, was to provide land to the 3 sons who had followed him to the new world – Aaron, Moses and Samuel.

On JUN 1661, just after moving to Oyster Bay, Robert bought and merged 2 home lots that became the core of his farm there. They must have been close to town because the council passed several rulings as to the width of the road passing through, and affirming the right of settlers to cross over on their way into Oyster Bay.

Then, in JUN 1665, he gave his sons Samuel and Moses 40 acres in Cold Spring Harbour. In DEC of that same year, Samuel bought out Moses and entered into a joint tenancy with his father on the Cold Spring Harbour property. That same day, Robert chose to re-partition his farm, giving one half to Moses on the condition he did not sell it in his parent’s lifetime. Aaron, probably the oldest and my ancestor, inherited the balance of the farm on his mother’s death. Robert Forman’s will is dated 7 FEB 1670, and he died 2 FEB 1671, leaving a long trail of records behind him.

First, I give to my loving wife my house, barn and orchard, and home lot, and the meadow at Matinecock, and all ye hollow at ye Plain Edge, and a hollow on ye Brushy Plains for my wife to dispose of as she see best for her comfortable subsistence, while she liveth, and if my son Aaron will undertake this for his mother, my will is that he shall do it, and improve ye aforesaid house and land for her, before any other, and at my wife’s decease, ye above mentioned house and land to be my son Aaron’s—to him and his [heirs] forever.

His wife, Johanna Pore, died the following year on 6 JUN 1672 and we know precious little about her. We know she was illiterate – she signed contracts with a mark. We know she was wealthy – we have an inventory of possessions taken on her death. But it’s frustratingly hard to research women in this period – often not even their name survives. In Johanna’s case, we got lucky.

Aaron Forman 1633-1698

Aaron Forman, my 9th great-grandfather, was probably born in Vlissingen and emigrated with his parents to Flushing when he was about 12 years old in 1645. He followed his father to Hempstead and by the age of 20 was keeping his own herd of cattle. In 1658, Aaron received a 15 acre land grant but most of the Hempstead records relate to taxes or the assignment of community labour.

The most interesting record came just after his land grant, when he was reprimanded by Pieter Stuyvesant himself. Aaron, 25 at the time, refused to pay a beer and wine tax and then heaped abuse on the tax collector – just 2 weeks after his father had been appointed Hempstead Magistrate.

The New Netherlands Council decided to respond with a hand-delivered warning. Two days before Christmas, Pieter Stuyvesant wrote a letter in English – clearly not his first language – gently telling the men to get their act together, or more serious charges would follow. Aaron complied.

Loving friends. What us and our Councell have forced to doe this message and Warrant unto the magestrates and other persons therein specified you fully may understand out the tenure of the mandement these feu lynes only shall serve to advys you if you will and kan take the good counsel of a friende and Governour that you and the Rest of your neighbours compose the differences with the Customer or his agent Ritehard Bridnel otherwise I feare that it will bread more disturbance to your one Charge and Damage Soo after my Love I shall Rest The 23d of Decemb Your well willinge friende A 1658 and Governour P Stuyvesant

Pieter Stuyvesant’s Letter to Aaron Forman over heaping abuse on the liquer taxman

He was married around this time to a woman named Dorothy – her surname doesn’t survive. And he was chosen by lottery on 26 FEB 1660 to serve on the town council. But other than writing an ordinance requiring damages for cattle grazing in the wrong field, nothing much more of interest is done by Aaron Forman in Hempstead.

His father Robert moved to Oyster Bay in 1661 but Aaron didn’t follow him there. He moved to Jamaica, Long Island – probably around 1665 when he gave away a piece of land in Hempstead. He was still living in Jamaica when his father died and, on 12 JUL 1671, he sold off the last of his Hempstead property.

Aaron probably moved to Oyster Bay when his mother Johanna died in 1672 and he inherited one half of his father’s 2-lot farm. His brother Moses, you’ll remember, was given the adjacent lot while their parents were still alive. Following the trail of deeds, we know that Aaron purchased more land in Oyster Bay in 1676 and sold off the last of his property in Jamaica in 1677.

Then in 1678, he fell out very publically with his brother Moses.

Moses lasted only 6 months in a joint tenancy with his other brother Samuel, and later abandoned his wife Hannah leaving the town in charge of his estate – so Moses was probably rough going as a partner. After 6 years of sharing the 2-lot farm, they could not see eye to eye. Two days before Christmas, a court ruled on the division of their father’s farm. Aaron was given 4 months to remove his barn from a portion of the property belonging to Moses, and Moses was required to pay for a fence between the properties because that was a condition of the original deed from his father.

And whereas Aron hath built a new barn upon Moses Lott as doth Apeare by ye line of divition ye Sd Aron hath liberty hereby to remove of ye said barne betwene this day & ye last of Aprill next Insuing ye date hereof upon his owne ground without hinderance or further trouble, & to pay satisfie & Cleare all ye Just Charges Accationed in ye prosecution in this sute, at ye Last Court of Sessions upon ye settlement or divition of these two Sd Lots managed & prosecuted by John Rogers for & in ye behalfe of Moses his wife & Children and further it is to be understood that it is fully agreed yt If the Sd Aron cannot with conveniancy remove his barne by ye time perfixt & Moses fforman his heires or Asignes hath A desire ye Sd barne should stand where itt now stands for his or theire use. yt then ye Sd Moses his heires Or Asignes shall pay for ye Sd barne as two honest men shall Judge itt being mutually chosen betwene then to be worth & as for ye fence yt Aron hath set up Upon his own Charge betwene ye two Lotts he hath liberty to remove but If Moses fforman hath A desire his heires or Asignes or John Rogers Now Concerned with ye Sd Moses Lands hath A desire to have part of ye Sd fence, to fence ye part or proportion betwene ye said two lotts according to their fathers gift or determination herein yt then ye Sd Moses his heires or Assignes or any man Consernd in ye Sd Lands of Moses shall satisfie for ye said part of fence.

Less than 10 years later, at about the age of 55, Aaron packed his bags and moved again – this time to Monmouth County, NJ. The county was established in 1683 and his sons Samuel and Thomas went immediately to settle in the area.

His namesake, Aaron Jr, stayed in Long Island and was given some of his father’s property in APR 1686. That deed was witnessed by Dorothy, who signed her own name, and Aaron Sr., who signed with his mark. Then on 11 APR 1693, Aaron ‘of the County of Monmouth and Province of East Jersey, planter’ cut his last tie to Long Island and gave his son Alexander his portion of Robert Forman’s farm.

I can’t find Aaron’s original deed in Freehold but other deeds reference it’s location off the Burlington Path – originally a Lenape trail and later a stagecoach road from Bordentown to Long Branch. All the Formans purchased property in and around what is now Rte 537, north-east of the city of Freehold.

Dorothy died sometime after 1693, Aaron in 1698 and they were likely buried in the Forman Burial Ground, where their sons and grandsons were buried – though no headstones have been documented for them. The cemetery sat roughly between 10 Hilltop Rd and 8 Longview Ave in Freehold and it remained intact for 265 years. In 1963, what remained of it was relocated to the Old Tennent Cemetery to make way for a housing development.

Samuel Forman. 1662-1740

Samuel Forman, my 8th great-grandfather, was born in Hempstead, Long Island in 1662, but his family moved to Jamaica, Long Island when he was just a toddler and then to Oyster Bay when he was about ten years old.

Before the invasion of New Amsterdam in 1664, Oyster Bay was the southern tip of British New England. It was a key port city and coastal trade with settlements to the north was an important part of its economy. Beyond that fact, I have no way to explain why Samuel Forman got married in Portsmouth, Rhode Island before the age of 22. He must have traveled there for work or trade, but I can’t find a record of it.

His wife, Mary Wilbore, was the daughter of Samuel Wilbore, Jr. and Hannah Porter. Their families – and some other like minded souls – were booted from Plymouth Bay Colony for deviating from accepted doctrine. Two of Mary’s grandfathers, my 10th great-grandfathers, signed the Portsmouth Compact on the 7 MAR 1638, establishing the city of Portsmouth, and breaking religious and political ties with England – but that’s a story for another day.

Shortly after their marriage, in SEP 1684, Mary’s father died and left them property in Narragansett country. They were living in Oyster Bay at the time, but the inheritance didn’t carry them back to Rhode Island. Instead, they moved south and bought land just outside of Freehold, in the newly formed county of Monmouth, in the Province of East Jersey.

Samuel must have put down roots in Freehold between 1685 and 1689, when a neighboring deed mentions his property along the Burlington Road. His brother Thomas joined him there and by 1693, so did his parents.

Samuel, his father, his siblings and his children all expanded their family holdings, buying up plots of land in and around Samuel’s farm – so much land, in fact, that the whole area was called Forman’s Neighborhood.

Samuel was named High Sheriff of Monmouth County on 29 NOV 1695. The office dates back to Saxon England when a ‘Shire Reeve’ was appointed each year to maintain law and order on behalf of the Crown. In fact, a High Sheriff is still appointed every year in every county of Great Britain, though it’s become a ceremonial honor.

In Samuel’s day, the job still had teeth. During his 1 year appointment, he oversaw tax collection, peacekeeping, the lower courts, and elections of the General Assembly. He was given his appointment by Governor Andrew Hamilton, a merchant and immigrant from Edinburgh, Scotland. Remember his name – it comes up again.

The Governour and Proprietors of the Province of East New Jersey—to all persons to whom these presents shall come—Greeting.—Know yee that wee have Commissionated and appoynted and by these presents Doe Commissionate and appoint Samuell fforeman of ffrehold of the Countie of Munmouth—Gent. High Sherriffe of the said Countie of Munmouth for and during the time and terme of one whole yeare now next ensueing. And wee doe hereby in the King’s name, and by his Authoritie Comand all Justices of the peace, Constables and other officers—And all the freeholders and Inhabitants of the said Province to be Aiding and Assistant to the said Samuell fforeman, in all things as Sherriffe of the said Countie, which to his office doth belong and appertaine. Given under the Seale of the Province, this twenty ninth day of November, in the seaventh year of the Raign of our Soveraign Lord King William over England, Etc. Anno Dom. 1695. By order of the Governour, Andrew Hamilton. John Barclay, Deputy Secretary.

To understand the next 7 years of Samuel’s life, you’ll need to understand a bit about the colonial history of New Jersey.

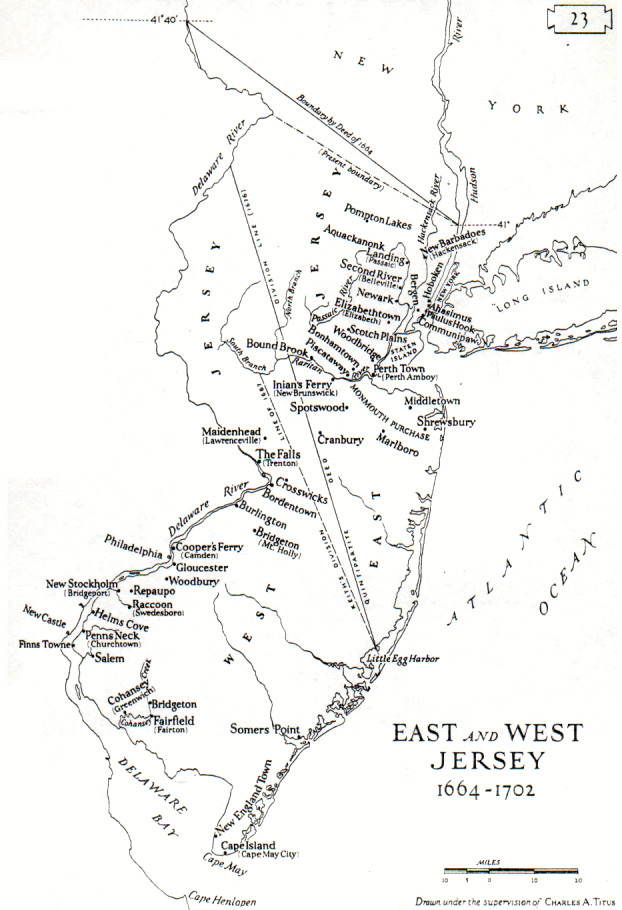

The southwestern portion was founded as New Sweden in 1638, and the northeastern portion as New Netherlands in 1614. The Dutch conquered New Sweden in 1655, and the English conquered New Netherlands in 1664. The Dutch continued to skirmish over New Jersey, briefly regaining control, and finally ceding it to the British in 1674.

Starting in 1664, the British Crown gave away parts of NJ, then reclaimed them, then gave them away again. And, of course, the Lenape nation was there before them all and sold property directly to the settlers. So one question plagued the colonial history of New Jersey – would property title be recognized by the next government to come along? It usually wasn’t.

Then, in 1675, a judgment in the bankruptcy of Edward Byllynge split the colony in two, creating East and West Jersey. Byllynge was a ‘Proprietor’ and the Governor of West Jersey for almost 7 years without ever having set foot in the province.

Proprietors derived their land rights from the Crown and were given the land, as well as the right to govern. They had the freedom to establish their own laws and their own terms of settlement. In exchange, they were suppose to turn colonization into a speedy, cost-effective corporate venture. But this proprietary right was not always recognized by the Crown, and there was some question as to whose terms of settlement would be honored at any given time.

Samuel Forman arrived in the mid-1680’s when property title and governance were so mismanaged that over 200 settlers – Samuel and his 2 brothers among them – petitioned the King to abolish proprietary rule and send them a competent Governor. If you read the whole letter, you’ll see they have 3 primary complaints against the Proprietors – all related to land ownership, and the hostilities arising from a failure to honor land ownership.

The settlers bought land directly from the Lenape and they were originally told they would own it outright. But the Proprietors randomly re-claimed, re-sold or gave away land purchased by settlers, and they tried to charge tax or rent on purchased land. Worst of all, they antagonized the Lenape by surveying their land without permission and selling their land without buying it first. Then, after provoking Lenape attacks, they failed to provide the military protection that was promised in the terms of settlement.

In a bit of 17th century pandering, the settlers closed their letter to the king with an attack on the Scottish-born Governor. The King was plagued by uprisings and Parliament had just passed a law prohibiting Scots from holding public office. In a bid to gain the King’s sympathy, they made their support for his Scottish policy apparent, and also accused the Proprietors of failing to respect it – about 1/2 of the 24 Proprietors were Scottish.

On 25 MAR 1701, when Governor Hamilton was in court at Middletown questioning a self-confessed pirate, a man stood up in the gallery and shouted that the Governor and Justices had no authority to hold court. He called for a drummer to drown out the proceedings and then 32 named men – Samuel Forman among them – freed the pirate and took the Governor, Attorney General, Justices, Under-sheriff and Court Clerk into custody. In an act of defiance against the Proprietors, the officials were held for 4 days and then released. Their supposed crime? Holding court while Scottish.

Later that summer, they sent a second petition to the King but it fell on deaf ears. The Proprietors were not removed from government until 17 APR 1702 when Queen Anne unified East and West Jersey under a Royal Governor named Edward Hyde, 3rd Earl of Clarendon.

But Hyde was no improvement – he was recalled within 6 years for accepting bribes and embezzling funds. He was also reportedly a cross-dresser – which would have been shocking at the time. In what can only be described as an act of genius, he claimed it was his way to more effectively represent the Queen. The New York Historical Society and the Dallas Art Museum both have portraits presumed to be of him in full dress.

With the coming of a governor, the East Jersey Board of Proprietors lost it’s right to govern, but it still owned land and it existed as a corporation until 3 SEP 1998 – dissolving after 314 years in business.

There’s not much more in the record for Samuel after the age of 40, though he lived to be 78. He bought a bit of land, he bid on an auction here and there – but mostly he carried on at the farm in Freehold.

Body of Mary Forman wife of Samuel Forman who died ye 13th day of March 1728 in ye 62d Year of her Age.

Here lieth the body of Samuel Forman who died ye 13th day of October 1740 in ye 78th year of his age

Mary Wilbur died on 18 MAR 1728 and Samuel 12 years later on 13 OCT 1740. They were originally buried in a family plot on a hill overlooking their farm, near what is now 10 Hilltop Rd and 8 Longview Ave in Freehold. But that cemetery – even that hill – are gone now. Whatever remained of the Forman graves was consolidated under a single headstone at Old Tennent Cemetery in 1963.

In a nod to karma, Samuel Forman – who arrested Governor Hamilton for holding court while Scottish – is now resting in a church founded by Scottish Presbyterians in 1692 – the same year that Andrew Hamilton was appointed Governor.

Aaron Forman. 1699-1741

Aaron Forman was born on his father Samuel’s farm in Freehold on the 22 MAY 1699. He was 1 of 9 children, and his siblings seem to have inherited none of the religious intolerance of the preceding generations. His brother Ezekiel married a Quaker and was buried at the Old Yellow Meeting House in Upper Freehold. Others married into the Old Brick Dutch Reformed Church in Marlboro. Aaron himself married a Scottish Presbyterian and his children were all given religious education at the Old Tennent Church in Manalapan, where he rented pew #29.

He married on 30 APR 1724 and his wife, Ursula Craig, was the daughter of Archibald Craig who immigrated as a child from Perth, Scotland. I’ve transcribed 3 of Archibald’s deeds and amazingly his farm is still intact. The Craig House, built by his son, enlarged by his grandson, and briefly owned by Archibald himself, was occupied by the British in the summer of 1778 – so now all of it is preserved as Monmouth Battlefield State Park. But thats a story for another day.

Aaron was a merchant and did business in Matawan and Freehold, but the most salient aspect of his life is that it was heartbreakingly short. The majority of what we know about him comes from his last will and testament, which he wrote at the age of 53 as he lay dying, preparing to leave his young wife and 7 children.

Principally & first of all, I Give and Recommend my Soul to Almighty God my most merciful Creator, trusting for Salvation in and thro His alone Merits of my Ever-Blessed Redeemer Jesus Christ. And for my Body, I recommend it to the Earth to be Decently Interred at the Discretion of my Executors hereinafter named; nothing doubting but at the Resurrection I shall receive this Same again by the Mighty Power of God.

Read Aaron’s transcribed will

He wanted most of his possessions sold to raise capital for the maintenance of his children, and for his family to stay on at the farm until his eldest son came of age. He planned for all of his children to be educated up to the age of 14 – including his daughters – and made provision for the continuing education of his sons, if they wanted to pursue it.

His sons were to be set up in professions and all his children were to receive some money when they came of age. He parcelled out his wealth, in fractions of 19, planning for every conceivable contingency, including what his wife should or should not inherit or control, when and if she should remarry. Unusually for the time, he asked for Ursula to be one of his five Executors, and the courts allowed it.

Here lieth the body of Aaron Forman, who died the 13th of January, 1741, in the 53d year of his age.

He died on 13 JAN 1741, exactly 3 months after his father Samuel, and was laid to rest in the Forman Family graveyard on Samuel’s farm. Ursula was only 37 when her husband died, and she never did remarry. She lived for 27 more years, first at the farm and then in Middletown with her son Lewis, who was only 10 when his father died.

She ultimately bought her pew outright in Old Tennent Church and held it all her life – it was sold by Lewis after her death to a member of the Craig family for £11 s10. All 7 of her children survived to be named in her will, and Aaron must have provided well because she still had some wealth when she died. Her first bequest forgave loans to her eldest son George and her daughter Priscilla’s husband – but other than some clothing, she gave them nothing further. The remaining 5 children – Lewis, Andrew, Robert, Lydia and Phebe – inherited her entire estate.

Son George, the bonds I have of him. Son-in-law, George Walker, bonds due to me from him. Daughters Priscilla, Lydia and Phebe, my apparel. Son, Lewis, Bible. Rest of my estate to my sons Lewis, Andrew and Robert, and to my daughters Lydia and Phebe. Executors – son, Lewis.

Ursula Craig Forman’s Will. 16 MAR 1768

She died on 4 APR 1768 and was laid to rest beside her husband in the Forman Family graveyard. They were the last in my line to be buried there.

Here lies interred the body of Ursula, wife of Aaron Forman, who departed this life the 4th of April, 1768, in the 64th year of her age.

All of those graves were moved to Old Tennent Cemetery in 1963, and whatever remained is memorialized under a single headstone. Some of the dates on that new stone – particularly the birth years for Ursula and Aaron – appear to be wrong. Perhaps the original epitaphs were too worn to read in 1963. For this research, I use birth years derived from the epitaphs on their original headstones, as recorded by Burtis in 1890, and Paxton in 1904.

Lewis Forman. 1730-1805

Lewis Forman, my 6th great-grandfather, was born on the 24 NOV 1730. He was a merchant and lived in Freehold until the age of 23, and married Affey Van Emburgh in Middletown at the age of 25.

Affey descends from the founders of New Amsterdam, including Jesse De Forest, my 11th great-grandfather. Jesse petitioned both the English and the Dutch for the right to establish a colony in America – eventually sending 60 families, including his own, to settle what would become New York City. A monument in Battery Park calls him out by name – but that’s a story for another time.

Because Affey was just 2o, her parents Peregrine and Cornelius needed to consent to the marriage and they made Lewis pay a £500 marriage bond – about $15k today – to have the union officially sanctioned.

Before 1665, the colonies followed the European practice of reading Banns for several weeks prior to a marriage. This would allow anyone who knew of an impediment to step forward. If the couple were too closely related, or previously married or promised to someone else – the marriage would not go forward. But this system relies on knowing your neighbor’s history – and that just didn’t work in a nation of immigrants – so they switched to a cash bond. If the groom turned out to have a wife back in England, or if he just decided to skip town – the bond would be forfeit. This was incredibly expensive and so most marriages were not formally recognized in this way.

But Lewis was a wealthy man and by the age of 25 he was dabbling in real estate in Middlesex and Monmouth Counties, perhaps with the money his father left him. When his mother died in 1768, he and Affey left Middletown and set up shop in Manhattan – so they were in Manhattan, not Middletown, as the events leading up to the Revolutionary War unfolded.

In 1903, a genealogist named William McClung Paxton described Lewis Forman as a Loyalist without ever explaining why he believe that to be true, and for 115 years others have echoed that charge – but it turns out to be completely wrong. Walking step by step through his actions during the war, I found a mountain of evidence to suggest that Lewis Forman supported American Independence.

One month after the Boston Massacre, in APR 1770, Lewis baptized his son George at the 2nd Presbyterian Church in Manhattan. Later that summer, he joined a multi-colony boycott of British goods in retaliation for the Townshend Acts.

His daughter Mary was baptised at 2nd Presbyterian in DEC 1772, just one year before the Boston Tea Party. The Continental Congress began meeting in SEP 1774, and by the time the first shots were fired at Concord and Lexington, Lewis and Affey had fled back to Middletown, NJ.

On the 3 JUL 1776, the British seized control of New York City and held it until the end of the war.

To understand Lewis, you need to understand that in colonial Monmouth County, the Revolutionary War was a Civil War, and it was a bloodbath. Of the 12-15,000 residents, 10% died or went into exile, and 50% of all families suffered property loss, injury or death. A researcher named Michael S. Adelberg, was able to document the names of about 6,500 Monmouth County residents and identified the political leanings of 3,714 of them – thats about 25% of the total population.

- 627 were Revolutionaries and did military service for the Continental Army or NJ militia

- 1,270 were Whigs, who did not do military service but signed petitions or paid taxes in support of the militia.

- 866 were Loyalists and volunteered for the British forces, or fled behind British lines.

- 674 were Disaffected. They did not do military service for the British, but withheld support for the militia. They were not always political – Quakers were often in this camp.

- In Middletown, where Lewis lived, 10 of the 29 men who held office between 1770-76 became Loyalists.

The split is fairly even and the prevailing wind of war determined who was running the county. It didn’t stabilize under Whig control until 1779, and what we would now call civil rights violations and war crimes were rampant – and mostly led by Lewis Forman’s first cousin, David Forman.

- 1776. David Forman jailed 100 suspected Loyalists without trial.

- 1777. He sent armed men to the polls to compel votes for his preferred candidates, and beat people in the street.

- 1777. He was forced to resign his commission as Brigadier General in the NJ Militia because the NJ Assembly was investigating the election that got him his commission.

- 1777-78. He used soldiers to guard and work in his privately-owned saltworks. Washington removed him from his command in the Continental Army over this.

- 1779. 120 Loyalists estates were confiscated and auctioned – sometimes without due process, and sometimes at auctions rigged to benefit the confiscators.

- 1780. David Forman sent armed men to the polls for a second time, closed the polls early to block moderate voters, and beat and threatened people in the street.

- 1780. He led an unauthorized, vigilante group called the Association for Retaliation which deported, hanged and generally took revenge on suspected Loyalists, and he enouraged his group to go after their families as well. He was a Monmouth County Court Judge at the time.

Radical and moderate Whigs were split on the need for due process and the protection of individual rights, but they were allies in the fight for Independence so they tolerated each other until about 1780. The contempt for law shown by the Retaliators was eventually too much for moderate Whigs, and they joined with the Disaffected, in condemning David Forman and the radicals. David Forman left NJ after the war, and never returned.

So was Lewis Forman a Loyalist? No, he wasn’t. He signed petitions and paid taxes during the war which indicate he “zealously supported the cause” of Independence.

- On 25 FEB 1778, he petitioned for a better provisioning of the NJ militia. (National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution Library, File Cabinet, Folder: John Lloyd of New Jersey.)

- On 24 MAR 1779, he petitioned the NJ Legislature to address corruption by the Auction Commissioners entrusted with the sale of confiscated Loyalist properties. He wanted fair and impartial due process for those who would be deprived of their property,

- On 31 MAY 1779, he petitioned on behalf of Patriots targeted by the British and left destitute because of their service. He also complained that the burden of military service needed to be shared more equitably.

- In DEC 1881, he denounced his cousin David’s Committee for Retaliation and described it as “a Tyranny set up among us.” The petition describes violent acts of voter suppression, criminal assault and plunder done in the name of patriotic retribution. He asked the legislature to restore and uphold trial by jury and free elections.

In each petition, the state’s authority and the cause of Independence are affirmed, and he paid taxes to the state in 1778, 1779 and 1780, including the Supply Tax in 1779 and 1780 – a tax specifically intended to fund the war.

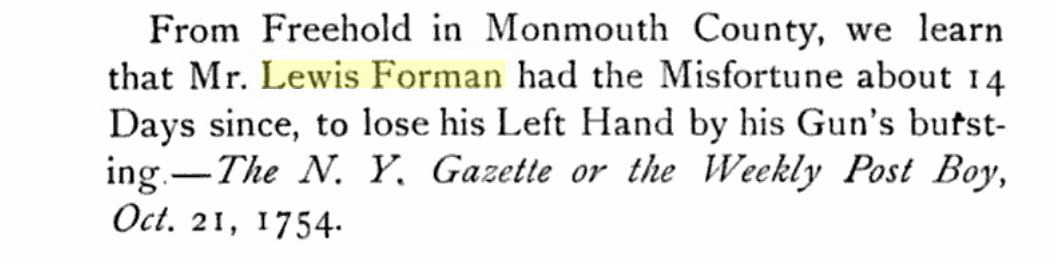

Paxton’s charge of Loyalism may stem from the fact that Lewis did no military service during the war. He was young enough to serve, members of his family did serve, and service was compulsory for able bodied men – but Lewis was not an able bodied man. A gun burst in his left hand when he was just 23, and he lost the entire hand. The accident was so exceptional, it made the papers as far away as New York City. So I would bet his lack of military service had less to do with his political principles, than his inability to load a musket.

All in, including his participation in the 1770 boycott of British goods, Lewis Forman took 10 documented actions which demonstrate his support for the cause of Independence. Given his injury, we can’t make much of the fact that he didn’t serve in the militia. But, at a time when Loyalists were fleeing to New York City to fall behind the British lines, Lewis Forman fled to Monmouth County and didn’t return to New York until after the war.

Paying the Supply Tax even once would enable his descendants to join the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution – Lewis paid it twice. I can’t tell you that Lewis Forman was unconflicted, but I can tell you that William McClung Paxton got it wrong – Lewis Forman was not a Loyalist.

The battle ended for most of the country after Yorktown in OCT 1781, but it raged on in Monmouth County for a full year more. The British held Sandy Hook longer than any other piece of ground in America and The Treaty of Paris wasn’t signed until 3 SEP 1783.

After the war and by 1786, Lewis was living in New Brunswick, NJ. We know that because he joined the First Presbyterian Church there and signed 2 more petitions – one in 1786, related to bridges and roads; and one in 1788 approving the newly proposed Constitution.

It’s not clear how long Lewis lived in New Brunswick – he was also paying tax on a property in Upper Freehold – so some of this may have been real estate holdings. But we know he was still there in 1791 when he took on the job of selling his brother-in-law’s New Brunswick property at 12 Water St – it was ultimately sold to Lewis’ son, William Forman, my 5th great-grandfather.

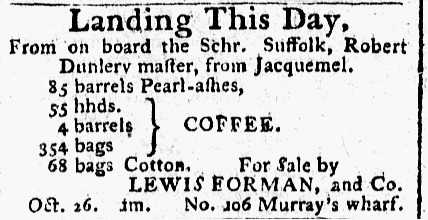

We do know Lewis ended his days in New York City. He had a shop at 136 Front Street in 1798 but, by the end of that year, he moved his shop to 106 Murray’s Wharf, which use to be at the foot of Wall St. He sold goods there for the last 7 years of his life.

Lewis died in New York City on 13 OCT 1805. He was buried near his son William at the First Presbyterian Church in New Brunswick, NJ. His remains were moved to Van Liew Cemetery in early 1921 – there is no marker. Affey survived him by 4 years and died in New Brunswick, probably at her son William’s home.

William Forman. 1767 – 1829.

William Forman was born 22 MAY 1767 in Middletown, NJ but his parents moved the family to Manhattan when he was about 3 years old. Tensions escalated with the British when he was 8 and the family moved back to Middletown for the duration of the Revolution. He would be 16 before the war was over.

He came to New Brunswick with his father after the war, probably around 1786, and he married Eleanor “Nelly” Pool at the age of 21 in the First Presbyterian Church on 10 MAY 1789.

Nelly was the daughter of John Pool and Sarah Field. Her brother John owned the Cornelius Low House, which still stands, and her mother’s family descended from Robert Field, a Yorkshire separatist who first settled in Portsmouth, R.I. in 1638 and later, like Robert Forman, was one of 18 patentees in Flushing, Long Island in 1645. But unlike Robert Forman, Robert Field stayed in Flushing. He was 1 of the 30 men who signed the Flushing Remonstrance in 1657. But that’s a story for another day…

Two years after William married, his father attempted to sell a house in New Brunswick on the Raritan river belonging to his uncle John Van Emburgh. The property was offered for sale starting in FEB 1791 but was to be rented if it didn’t sell by MAY.

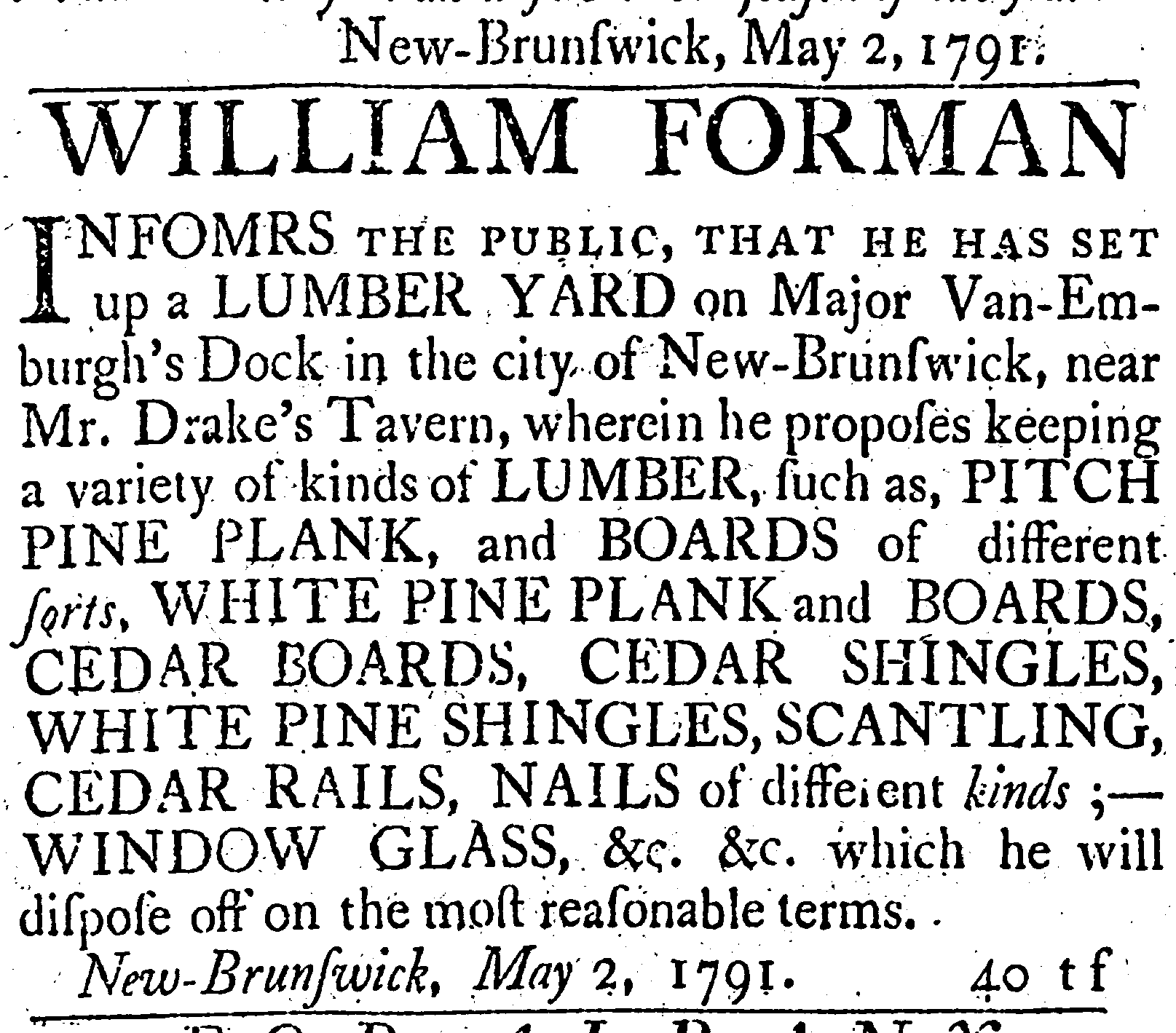

On 2 MAY 1791, 24 year old William announced that he would set up a lumber yard there. He started out renting the property from his uncle John but then on the 9 NOV 1792, he bought 12 Water Street in New Brunswick for £750.

All that Messuage and Tenement and all that lot, piece or parcel of Land….beginning at the south east corner of John Taylor’s lot at a post on the west side of Water Street, and from thence running west, Seventy Six degrees and thirty Minutes West, two hundred and fifty seven feet along said Taylor’s line, Thence South four degrees and fifteen Minutes East Sixty feet along James Parker’s line to a post for a corner~ Thence [north] Seventy Eight degrees East two hundred Eighty five feet to Water Street, Thence North twenty seven degrees west Sixty Seven feet along Water Street to the place of beginning.

The street numbering changed a over time and today not even the street survives but in William’s day, Drake’s Tavern was on the corner of Water and Albany (formerly French St) and there was a ferry crossing next to the tavern where you would now find the Route 27 bridge.

William’s lot was next to the tavern, extending all the way from Peace St. (formerly King St.) to Water St., and then across Water St. down to his wharf and the low water mark of the Raritan river. The house itself was a comfortable 1156 square feet, with 4 rooms on each of 2 floors and a stone cellar.

The yard would have flooded when the Raritan spilled it’s banks and over time, as William added outbuildings to the property, he was careful to plan for drainage – designing stone floors with channels for run-off.

We know a lot about William’s life there because Water Street was partially excavated in the late 1970s and then entirely excavated in 2oo3. They found glassware belonging to William, or more probably to his uncle John, and then uncovered a stone floor laid by William for a warehouse which later became the foundation of a tenement building.

William ran his lumber business from 12 Water St. for 20 years before selling it to his wife’s nephews Peter Vanderbilt Pool & John Adams Pool for $4,000.00 in MAY 1811. The nephews had a business in Raritan Landing and this location was more central for them. Somehow the sale allowed William’s family to continue living in the home at 12 Water St. and they stayed on there until 1826 when John Harriott turned it into a boarding house.

If you’re wondering why William didn’t leave the lumber business to his children, I can’t tell you that. Nelly and William had 9 children. Their eldest died in infancy before they came to Water St. and the other children were all born on the property. Five of them lived to adulthood, 4 of them were sons and at least one of them was in the lumber business – so it’s a mystery.

William’s wife Nelly died after a “lingering illness” at 54 years old on the 25 NOV 1822. William followed her on the 9 MAR 1829. He was 61.

Like William’s parents, Nelly and William were originally buried at the First Presbyterian Church in New Brunswick but their graves were moved to Van Liew Cemetery in 1921 to make room for new construction. There are no grave markers.

Robert Forman. 1801 – 1848

Robert Forman, my 4rd great-grandfather, was born on 4 APR 1801 in New Brunswick, NJ. Five months later, the First Presbyterian Church recorded the baptism of an infant belonging William Forman on the 7 SEP 1801. Though it doesn’t list the baby’s first name, this is likely Robert’s baptism.

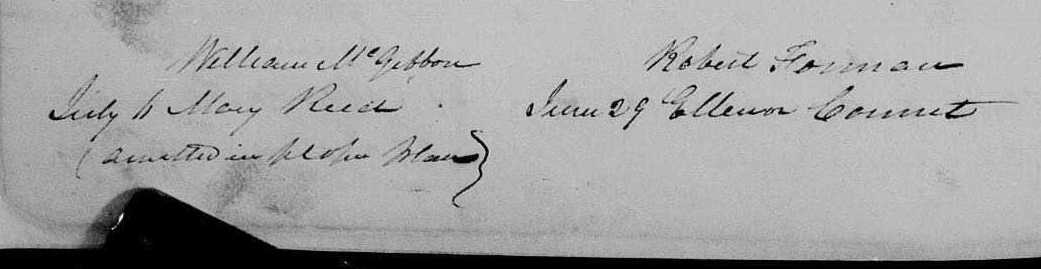

On the 29 JUN 1825, at the age of 24, Robert married Ellen Connet at the First Baptist Church of New Brunswick – but neither of them seem to be Baptist.

Their first and only child was born sometime in the 6 months following their marriage and so perhaps it was a way to be discrete about the timing. Or maybe they were flirting with his Anabaptist roots – I can’t tell you. I do know that 5 years later, Robert’s wife and her sister Mary would join the First Presbyterian Church of New Brunswick, and his son, William Spencer, would be baptized there as well.

Ellen was the 3rd great-granddaughter of Captain Thomas Gardiner who founded a colony on Cape Ann in 1624. Her great-grandmother Mehitable Gardiner was born in Charlestown, MA and married a British immigrant named James Connet. At the end of the 1600’s, they headed south with their children and were among the earliest settlers of Woodbridge Township, NJ.

Robert’s is the first generation for which we have census data – but that doesn’t tell you much. The 1840 census took a literal count of men and women by age group and only recorded a name for the ‘head of family’. From this limited information, we know that Robert was living in New Brunswick with 1 teenage age boy – almost certainly his son – and 2 grown women – almost certainly his wife and her older sister, Mary.

Beyond that, I can’t tell you much. I didn’t find a will. He isn’t listed in the 1829 directory map for New Brunswick. He’s mentioned 3 times in the local newspaper but only for letters left at the post office. There is one obscure reference to Robert selling timber but I don’t have a clear sense of Robert’s profession. In short, he left a light footprint.

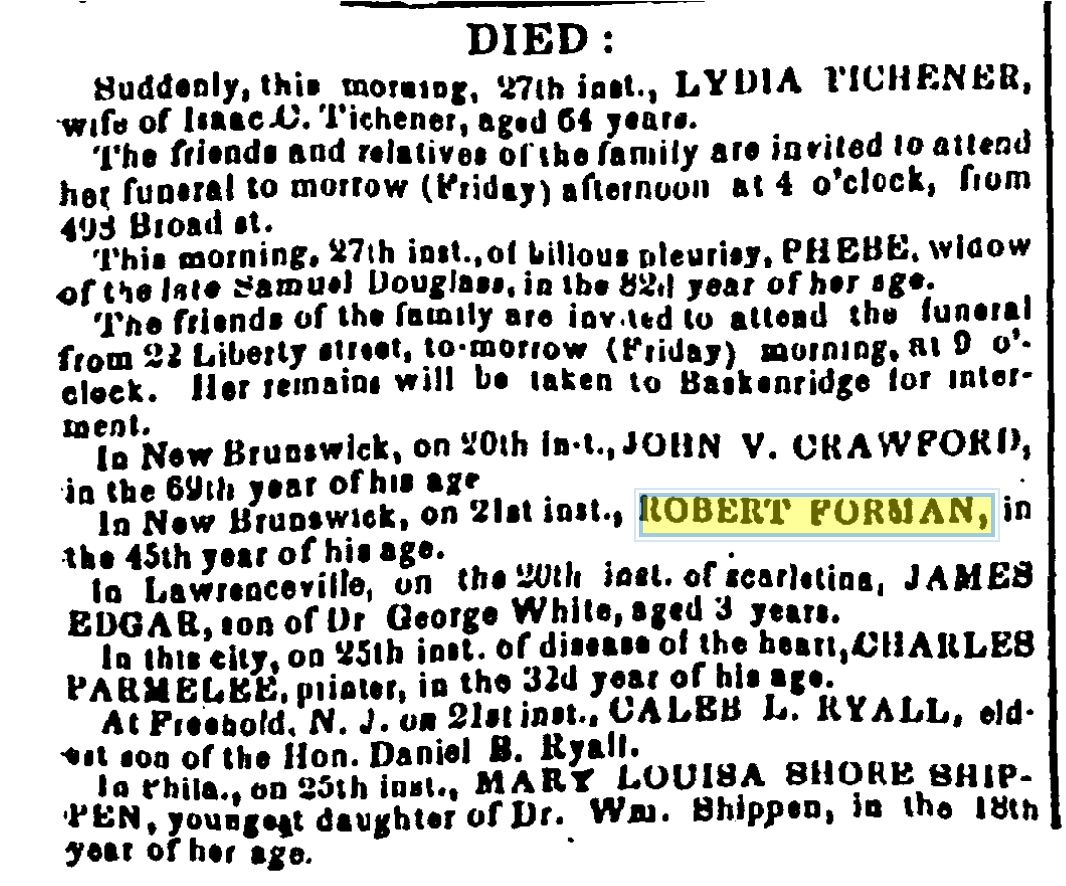

Robert died in New Brunswick on the 21 APR 1848, at the age of 47. Though his obituary was printed as far away as Newark, it tells us nothing about why he died so young and New Jersey wouldn’t begin recording death certificates until the end of 1848.

Ellen was 45 when her husband died and, though she had a son, she and her sister Mary were ultimately left well and truly on their own. They worked as seamstresses and continued to live together until Mary died in 1864.

I don’t know exactly when Ellen died but I believe it was between 1864 and 1870. She appeared in the 1860 census and I suspect she buried her older sister in 1864. Based on timing and circumstance, I think she took in her granddaughter, Catherine, perhaps as early as 1861. But in the 1870 census, her still underage granddaughter was fostered out with non-family members. So, by then, I believe Ellen must have died.

William Spencer Forman. 1826 – 1881

My 3rd great-grandfather, William Spencer Forman, was an alcoholic. If that seems an odd way to begin, I’ll tell you that for me it was the single fact that made sense of all the other facts of his life. There were periods of stability, periods of prosperity, and periods of loss and chaos. From a distance of 175 years, I could still see the wreckage of a struggle but until I knew he was an alcoholic, I didn’t understand why.

William Spencer was born in 1825, just after his parent’s marriage and he was named for both of his grandfathers; William Forman and Spencer Connet. In early census records, his mother fudged the exact year of his birth but later records are consistent, he was born in the second half of 1825.

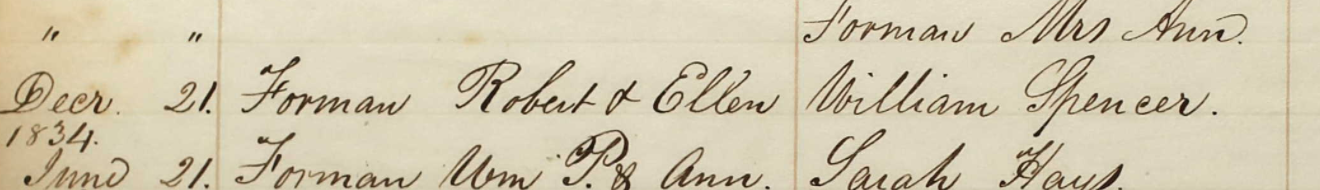

He was baptized at the age of 9 on the 21 DEC 1834 in the First Presbyterian Church of New Brunswick, and his upbringing is slightly remarkable in that – though his parents were married for 23 years – he was an only child. There are no other recorded births or baptisms, and I cannot tell you why.

He lost his father when he was 23 and continued to live with his mother and aunt until he married at the age of 26. His first wife, my 3rd great-grandmother, was Susan Parker Spader and based on the 1840 census, we know they grew up together in the same neighborhood of New Brunswick.

Susan descends on both sides of her family from the founders of New Amsterdam: including my 10th great-grandmother Tryntje Claes, who had a farm in her own right on Pearl Street in Manhattan in 1686; and my 10th great grandfather Isaac De Riemer, the 25th Mayor of New York City (1700-1701).

Susan’s family historically belonged to the Dutch Reformed church and William Spencer was a 5th generation Presbyterian, but they married in a Methodist ceremony under Reverend John D. Blain on 10 Dec 1851 in North Brunswick Township.

He claimed to be 24 – he was 26 – and she was just 19. Thirteen months later, they welcomed a daughter named Catherine on the 17 Jan 1853.

William’s second child, a son called William, was born 6 years later on 22 Aug 1859 – and Susan was not his mother. His mother was a woman named Elizabeth – last name unknown.

If you’re scratching your head wondering what happened, I can’t tell you. I presume Susan died sometime between the birth of her daughter in 1853 and the birth of William’s son in 1859, but I never found a death, burial or divorce record for Susan Parker Spader, and there seem to be no other children born to William until the birth of his son in 1859. Susan just disappears from the record.

Likewise, I never found a marriage record or even a maiden name for what appears to be William’s second wife, Elizabeth. It may have been a common law relationship, but I just don’t know. I do know that Elizabeth was born in New York, and was 24 in the year of her son’s birth. So if they fit the typical pattern of the time, they probably got together at the end of 1858, when she was 23 and he was 34.

What I can tell you for sure is that on 9 JUL 1860, William Spencer, Elizabeth and the 2 children were living in New Brunswick. William worked as a cabinet maker before his first marriage and became a sash and blind maker in the year he married his first wife, Susan. In 1860, he was in his 9th year as a sash and blind maker and had a personal estate worth $500. He was doing well enough to have a live-in servant named Bridget.

I can also tell you that 14 days after the census was taken, on 23 JUL 1860, his infant son William died of unknown causes and just 2 months later on 28 SEP 1860, his wife Elizabeth died of consumption. William Spencer buried his father, 2 wives and one son – all before the age of 35. Catherine, his daughter, was 7 at the time and as far as I can tell she never lived with him again.

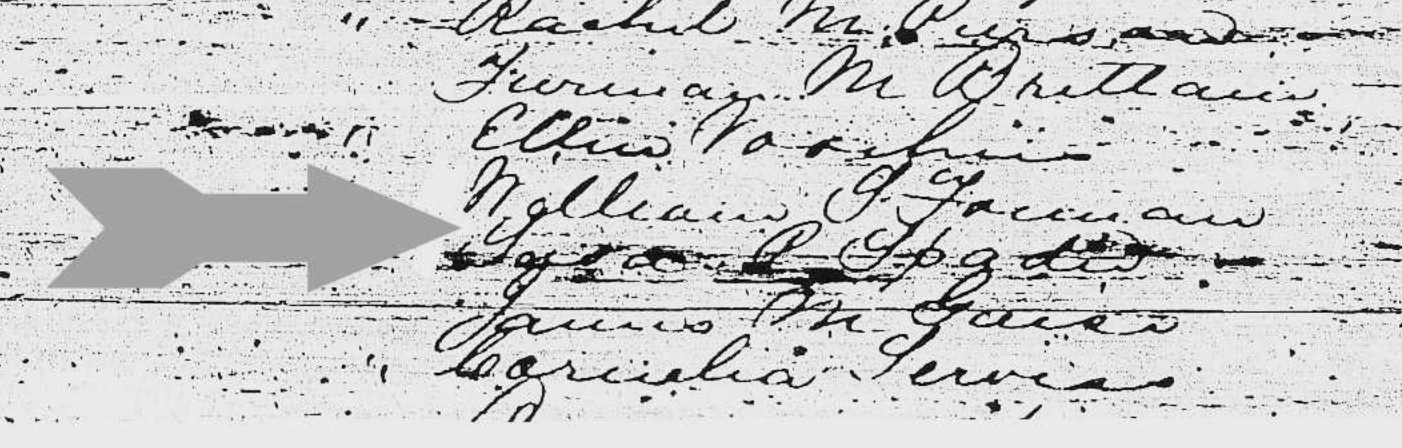

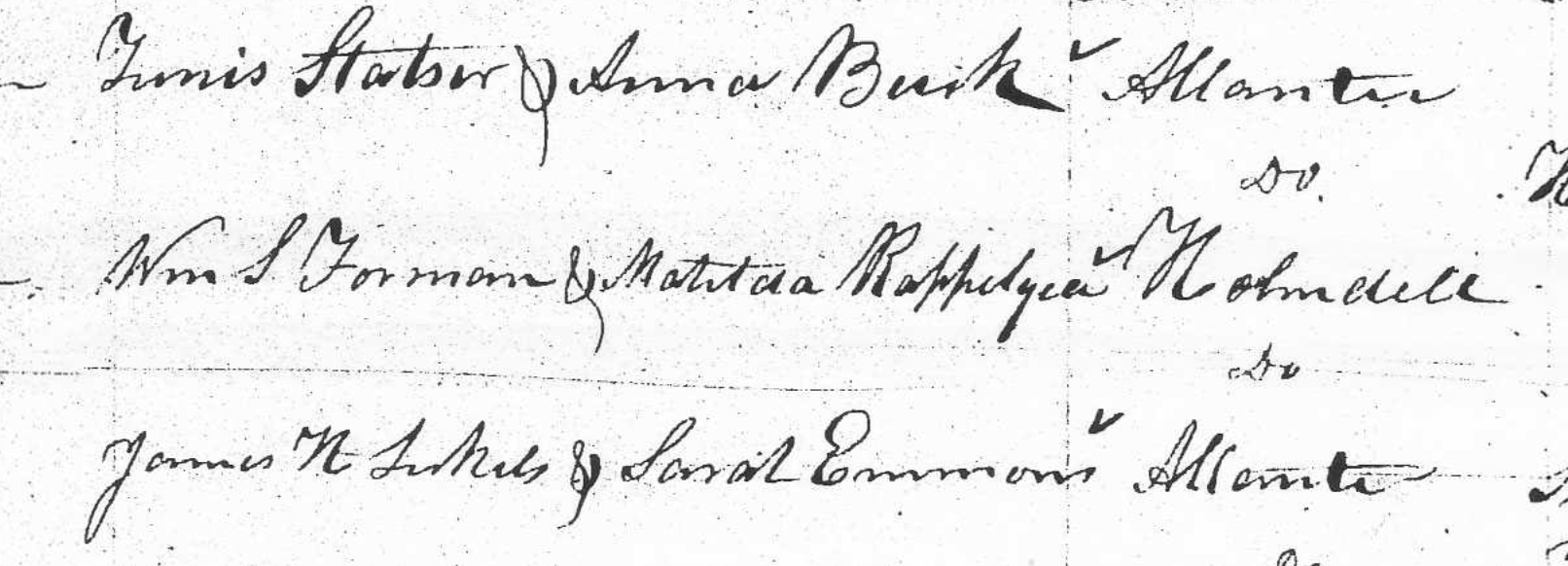

There’s no trace of William Spencer after 1860 until he marries his third wife Matilda Rappleyea in Holmdel on 5 JAN 1867. Matilda was descended from early Dutch settlers and her extended family were wealthy landowners in Franklin Township.

In their marriage record, William Spencer claimed to be 35 years old and a widower – he was actually about 42. Matilda was 48 years old and had never been married before. They were married by the Reverend James Bolton of the Dutch Reformed Church at Colts Neck. Neither gave their parents’ names, and neither listed a profession. To the best of my knowledge, they never divorced and never lived together again after 1868. Matilda returned home to live with her brother Tunis and survived William Spencer by 2 years.

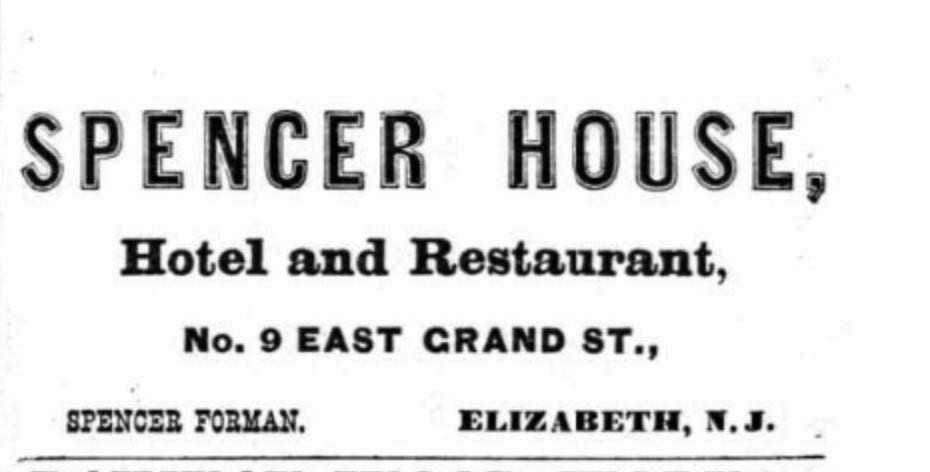

In 1868, William Spencer – going by just ‘Spencer’ now – was living in Elizabeth, NJ. He opened a boarding house at 9 East Grand Street and later moved it to Waverly Place. He stayed on there for just about a decade.

I believe his mother died shortly after he opened the boarding house in Elizabeth but his daughter Catherine did not come to live with him there. In 1870, at the age of 17, she remained in New Brunswick and was living with the widower Augustus Wetsell and his four children.

There is no familial connection between Catherine and the Wetsell family and her profession in the census is listed as ‘no occupation’ – which tells us she wasn’t living there as a servant. But Augustus was once a drape polisher by profession – he later became a jeweler – and newspapers referred to him as a “Temperance” man, so perhaps somewhere in those facts lies his connection to Catherine and her father.

By the summer of 1880, William Spencer established a boarding house at 45 Commerce St, in Newark with his 4th wife, Julia Forman. Julia was born in Pennsylvania and she was 20 years younger than her husband.

For those of you keeping track, his 3rd and legal wife, Matilda, was still very much alive and living 37 miles away in Holmdel.

Unusually, we know a lot about the end of William’s life from the proceedings and appeal of a divorce case, Paul v Paul. In short, Mrs Paul was abandoned by her husband and took up with Mr Leach who was boarding in her house. Mr Leach was also married and had likewise abandoned his family. Multiple people testified to public drunkenness and a “criminal intimacy” between them.

Mr Leach moved out of Mrs Paul’s house and became a bartender and boarder at Mrs Forman’s saloon where additional witnesses testified that the “criminal intimacy” continued until Mr Leach left the saloon, around the time of Mr Forman’s death.

In her appeal, Mrs Paul contested the testimony of the witnesses against her, citing their “low character”. At the time, being a person of ‘ill-repute’ meant your testimony could be automatically excluded. It was this court case, Paul v Paul, which shifted case law in NJ, and established that persons of ‘ill-repute’, who are otherwise credible on the facts, could be believed in court.

Both Julia and William Spencer are mentioned by their full names and, notably, the saloon is described in court as belonging to Julia, not William Spencer. Descriptions provided in the appeal leave little doubt that Julia was running a brothel and a saloon, and that William Spencer was probably a bartender there until Mr Leach came in to replace him after he was no longer able to work.

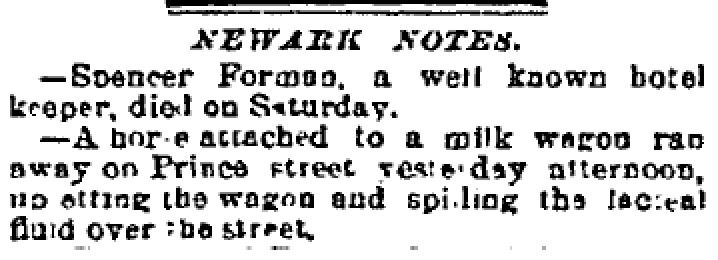

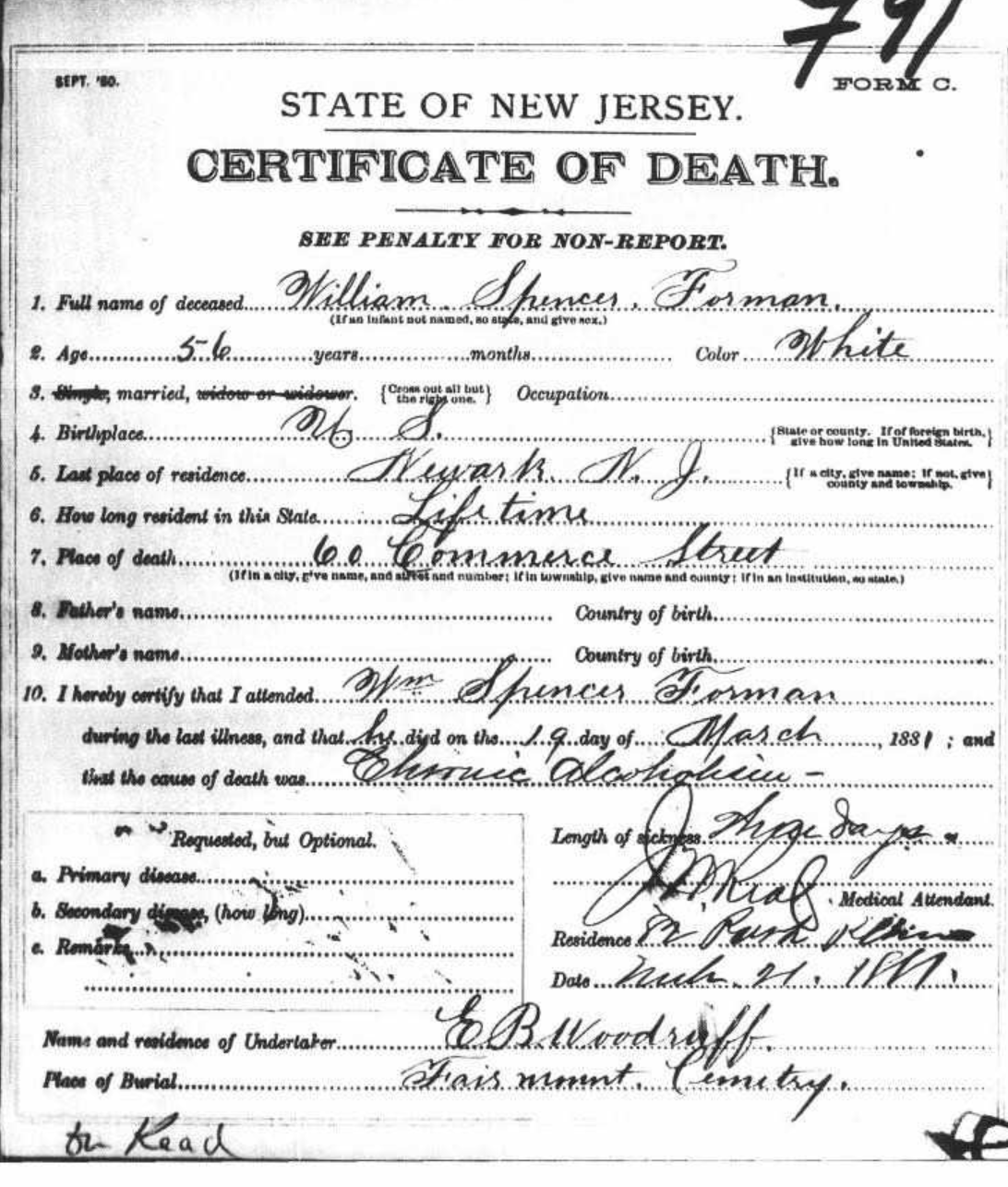

William Spencer Forman is the first generation for which we have death certificates – so I can tell with absolute certainty that he died of chronic alcoholism at 60 Commerce St in Newark on the 9 MAR 1881. He was buried at Fairmount Cemetery and I believe he lies there still. He was 56 years old.

Catherine Forman. 1853 – 1913

Catherine Forman was born in New Brunswick, NJ on 17 JAN 1853 and her early life was marked by repeated loss. Her mother probably died sometime between her birth and her 6th birthday. Her father seems to have stepped out of her life when she was about 7 or 8 years old, just after the death of her stepmother and baby brother. I believe her great-aunt and grandmother took her in – but they died by her early teens, leaving her to be raised in the home of Augustus Wetsell, a widower with 4 children, who was in no way related to Catherine.

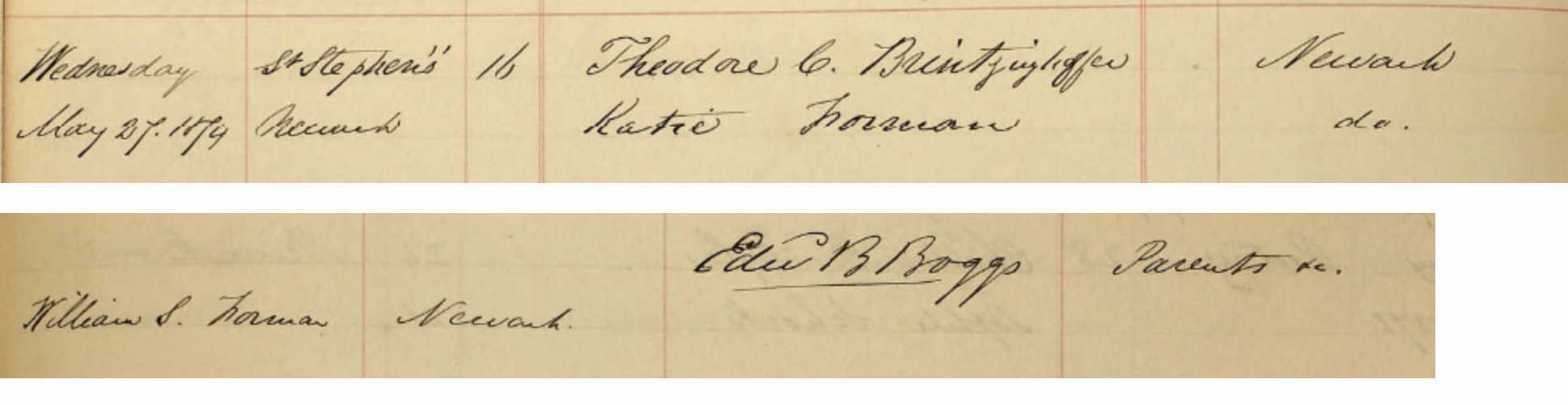

It’s not clear how Catherine met a well-to-do young man from Newark, but it’s not surprising that she married early. At the age of 21, on 27 MAY 1874, ‘Katie’ married Theodore Canfield Brintzinghoffer at St. Stephens Episcopal Church in Newark, NJ.

The groom’s father was George Washington Brintzinghoffer, a cigar manufacturer and a prominent citizen in Newark. Theodore, his first born son, was being groomed to take over the family business. If you’re curious to learn more about the Brinztinghoffers, you can read about them here.

When Theodore Clarence was born on 19 Sep 1876, they may have been living above the family cigar shop in Newark but by the time William Halsey Utter was born on 7 FEB 1878, they were settled in a house at 28 Chestnut St. Unfortunately, their happiness would be short lived. Not 4 years into her marriage and only 11 months after the birth of her second child, Catherine’s husband died of pneumonia on New Year’s Eve, 1878. He was 32 years old and Catherine was just 25.

I would love to tell you that Theodore’s family closed ranks around her but that doesn’t seem to be the case. Her father-in-law took her in only once, and only briefly, when her youngest son William was dying from pseudomembranous croup. He passed away at the age of 5.

Three years after her husband’s death, she lost her father, William Spencer.

Three years after that, she lost Augustus Wetsell. Her foster father went missing in New York City. The papers say he was in town with a detective on ‘official business’ and was last seen at a court house heading to his daughter’s house. He never arrived and was presumed murdered.

A year after that, Augustus’ son and Catherine’s foster brother, was carried off to an asylum at the age of 34. He attacked some boys, poking one in the eye with his umbrella. The newspaper description tell us something of what Catherine’s life may have been like in the Wetsell home.

The boys ought to leave him alone, as he is subject to fits and has a very violent temper… The fits with which he had been afflicted since childhood had weakened his brain, and at times he was positively dangerous.

New Brunswick Daily Times, AUG 1885

And all of this happened to Catherine before the age of 32. Catherine and her son, Theodore, would spend over 20 years living with some degree of instability and insecurity – moving from house to house and taking in boarders to make ends meet. When I first researched Catherine, I was stunned by the sheer number of blows she had to endure and, though there was a lot to admire in her resilience, I really wanted life to give her a happy ending.

Eventually, I think it did.

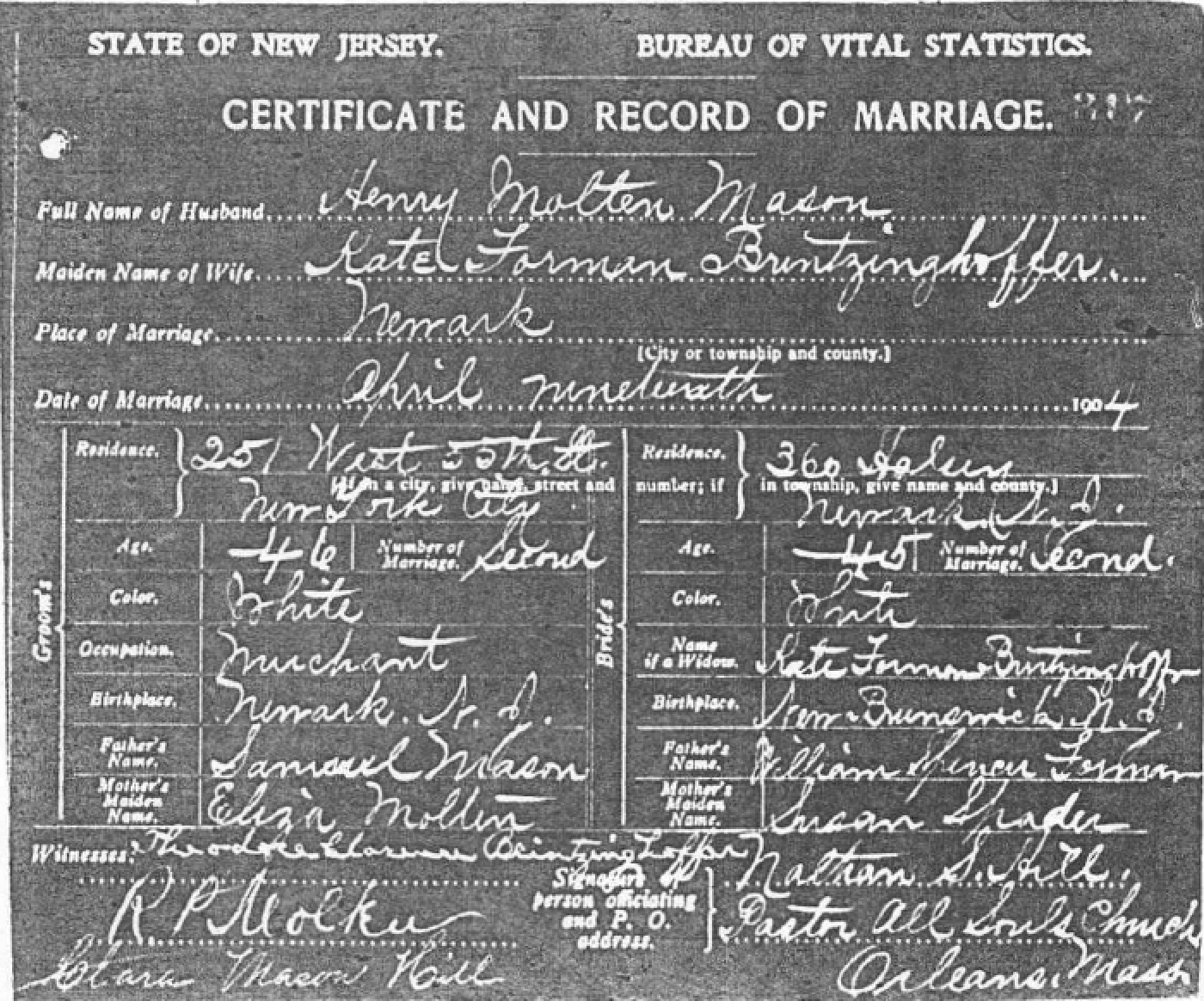

On 19 APR 1904, at the age of 51, Catherine married Henry Molten Mason, a salesman who had once been a boarder in her home. He was previously married with children. His former wife was very much alive and in Brooklyn, claiming to be a widow. But I believe they must have been properly divorced or annulled because both of Henry’s marriages were legally recorded in Newark and both were performed by clergy.

Henry’s brother-in-law, the Reverend Nathan Hill, a pastor at All Souls Church in Cape Cod performed the service, and Henry’s sister Clara and Catherine’s son Theodore were witnesses. Henry was 45, and ‘Kate’ claimed to be ’45’ as well. They immediately moved to Philadelphia where Henry worked for Slater & Sons as a woolen salesman and lived out the rest of their life together at 1010 Spruce St.

Catherine died of a stroke while vacationing across the river at the Lawn House in Riverside, Burlington on 1 OCT 1913. Henry followed her less than a year later on 29 JUN 1914. Her first husband Theodore and probably her son William are buried at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Newark, but it appears that Catherine was laid to rest with her second husband in Elizabeth, NJ.

Her death record indicates a burial at Greenwood Cemetery, Elizabeth – which doesn’t exist. So, presumably, they meant Evergreen Cemetery. Henry was laid to rest in the “open grave next to Mrs. Mason“.

Last words…

If genealogy teaches you anything, it teaches you that your life has been a cakewalk compared to those that came before you. I am constantly surprised at how much of them lives on in us and how patterns repeat across generations.

My parents built a home 10 miles from where 4 generations of my family lived and died in Freehold – and I didn’t know it. I lived less than 2 miles from where 5 generations of my family lived and died in New Brunswick – and I didn’t know it. I’ve walk down Pearl St, Wall St. and Broad St in New York City without knowing they once held the farms and homes of my ancestors. And when my mother first offered me my grandmother’s wedding ring, I didn’t know it had been worn by someone else before her.

Knowing – even in hindsight – makes the whole experience richer for me. The more I know about the people that came before me, the more I know how much of me comes from them, and how grateful I am to be reminded of it.